EUROPEAN SETTLEMENT

There is relatively little written about Michigan as it pertains to the American frontier.

This may be due in part to the unique geographical nature of the state and its rather

unusual history. The standard frontier histories bring a rush of settlers into southern

Michigan after the Erie Canal was opened, and, after a few paragraphs most historians move

on westward, leaving the people who came to Michigan in early 1830's to build up the

state. The implication is that with this start, Michigan grew in population by the natural

increase of its first settlers and by immigration, and that the vacant places were thereby

filled up, producing the Michigan of today. It also is implied that Michigan was

influenced in its growth not only by the experiences of pioneers prior to the 1830's but

also by the frontier as it moved westward across the continent. Nothing of this sort

really happened.

Source: Michigan

State University, Department of Geography

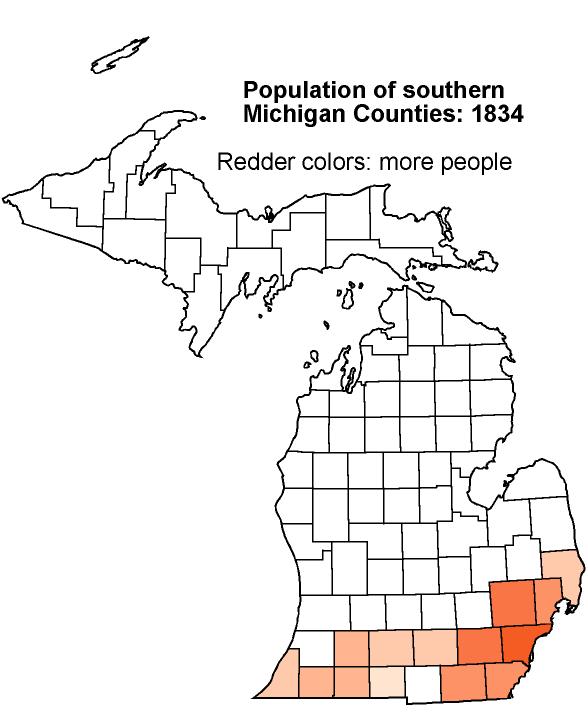

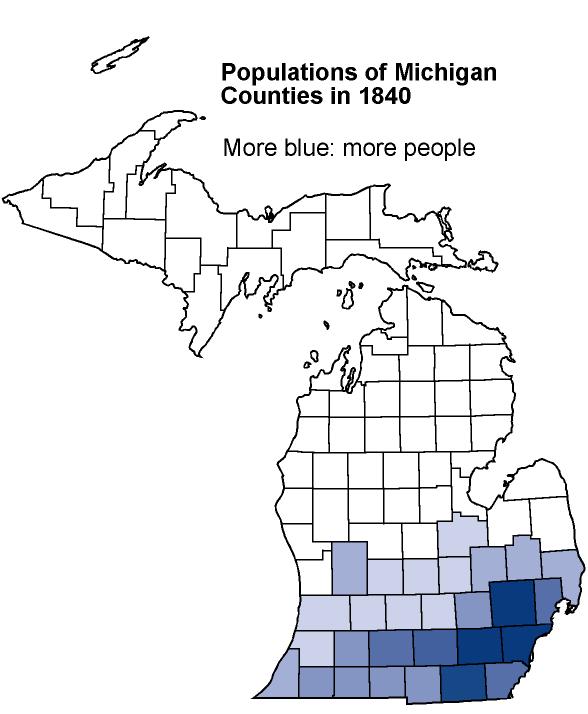

The Michigan frontier of the 1830's was confined to only about 25 of the state's

present 83 counties. It did not reach much further north than the four southern tiers of

counties. North of a line drawn through Muskegon and Bay City, the pinelands begin, and

underneath the pines the soil is thin and sandy. Furthermore, the growing season is

markedly shorter. Hence, pioneers seeking new farms by-passed northern Michigan and moved

on into Wisconsin and Iowa. They neglected Michigan's Upper Peninsula for the same

reasons. One writer on the West states that by 1848, when a great tide of immigration from overseas began, "Michigan was

so well integrated that much of this influx was forced to jump over into Illinois, Iowa,

and Wisconsin." Just what he means by his statement that Michigan was

"well integrated" in 1848 is obscure. The census of 1850 shows that over 98 per

cent of the state's population at that date lived in the southern counties of the lower

peninsula comprising about one-quarter of the state's total area. Only 7,649 people were

counted in an area of the north approximating the size of the state of Indiana. There

obviously was abundant public land left in Michigan, but its quality was such that it

could not compete for settlers with the more fertile lands further west, where the climate

was less severe.

Source: Michigan

State University, Department of Geography

In the 1840's, Michigan had a mining frontier of enduring importance to the

state and the nation, a fact that goes unmentioned in most of the histories of the

American West, though they deal at length with the mining rushes in the Far West. Yet the copper taken from Michigan mines, and the iron

ore produced in Michigan and across the state border in Wisconsin and Minnesota have

been of far greater importance in the building of the nation than the gold and silver

which came from the mining bonanzas of California, Nevada, and Colorado. A report made in

1841 by Douglass Houghton, the state geologist, was followed by a rush of prospectors to

the Copper Country of Michigan's Upper Peninsula and the establishment of mining camps

which had many of the characteristics of those a few years later in California. The

discovery of nuggets of silver with the copper added to the excitement. In 1844, iron was

discovered in another part of the Upper Peninsula and soon that ore, too, was being mined.

Michigan led the nation in copper production from 1847 until 1887, and in the production

or iron, Michigan ranked first until 1900. Of major importance in making the vast

quantities or ore in Upper Michigan accessible was the construction of locks and a canal

at Sault Ste. Marie.

The mining

frontier added a new dimension to Michigan's population. The dominance of New England

stock, so marked in the settlement of the farmer's frontier of southern Michigan, was

notably absent in the mining country, although Boston dollars were heavily invested in the

copper mines. The newcomers included at first workmen from the lead mines of Illinois and

Missouri. Heavy reliance was placed, over the years, on foreign immigrants. The

contributions of skilled miners from Cornwall were of inestimable value. There was a large

influx of Finns. Many Irish, Germans, and -after 1890-Italians, and other southern Europeans

came.

The migration of loggers, sawyers, rivermen, and investors in timber

from Maine to Michigan, then to Wisconsin, Minnesota, and the Far West played a vital role

in the development of significant portions of the nation. One writer on the American

frontier states that Michigan had nine times as many varieties of trees as Great Britain,

but he fails to note that one of them was the white pine, the lumber from

which was highly regarded because of its beauty and the ease with which it could be

worked. In 1847, a shipment of white pine lumber from Saginaw reached Albany, New York

where it was compared favorably with lumber produced in Maine, which was then the standard

of high quality. Shortly afterward, investors began the process of acquiring tracts of

timber in Michigan, and the migration of workmen, with their skills and tools, got

underway.

From 1860 until 1910, the harvest and sawing of logs and the marketing

of lumber was the major non-agricultural industry of the state. Immense fortunes were

made. One of the major reasons for the later concentration of the automobile

industry in Michigan was the fact that Detroit had men whose large fortunes had been

made in lumbering and mining and who were willing to invest money in automobile plants.

The movement of population into Michigan in the half-century during which lumbering was

dominant brought in a number of new elements. Among the workmen, Canadians, Irish, and Scandinavians, especially Swedes,

were heavily represented. But the proportion of foreign-born was not nearly so great in

the lumber camps as in the mining regions. Natives outnumbered foreign-born in 1890 in two

important lumbering counties, Muskegon and Manistee, by almost two to one.

Pine lumber from Michigan, Wisconsin, and Minnesota made possible the

building of farmhomes and barns, and Chicago was re-built after the great fire of 1871

with Michigan and Wisconsin pine. But the passing of the lumberman left to Michigan itself

a legacy of problems. Homesteaders and those who obtained land from the railroads or the

state tried, but in most cases failed, to make a living on the sandy soil in the cut-over.

Railroads, which had built lines into northern lower Michigan with the inducement of land

grants, were left with little traffic. The end of large-scale lumbering in the Upper

Peninsula, coupled with the decline, first of copper and then of iron production, brought

severe economic problems to that area. The relatively poor soils and the short growing

season repelled farmers; the distance from major markets did not make the region inviting

to manufacturing industries. The recreation industry, patronized

by tourists, resorters, and vacationists, became the major element in the economy of

northern Michigan.

This material has been compiled for educational use only, and

may not be reproduced without permission. One copy may be printed for personal

use. Please contact Randall Schaetzl (soils@msu.edu)

for more information or permissions.