Several key events opened the door for pioneer settlement. The 1825 completion of the Erie Canal opened a new and easy route to the territory via the Great Lakes and Detroit, and by 1833, federal Indian policies had removed most Native Americans to the west of the Mississippi, which paved the way for government land surveys and, thus, for increased agricultural settlement. It was these government surveys that divided the land into sections and townships, designations that are still applied, and greatly influenced the size and location of early farms.

The decline of the Indian in Michigan was foreshadowed by favorable reports on Michigan’s climate and resources written by Indian agents, army officers, travelers, and explorers. Land-hunger was whetted by maps with alluring notes and by books like that of the geographer William Darby, who saw Michigan in 1818 while helping to survey the boundary between the United States and Canada. After the Erie Canal was opened, settlers streamed into the Lower Peninsula, attracted by a flood of guides and gazetteers for Americans and foreigners. Enterprise was stimulated also by glowing descriptions of Michigan’s mineral resources, based upon the explorations of Dr. Douglass Houghton and William Burt.

Governor Cass (below) waxed enthusiastic at the prospect of development opened by the Erie Canal and saw in it the inevitability of statehood. His treaties acquiring lands, the beginning of public-land sales at Detroit in 1818, the start of steam navigation on the Lakes, and the actual opening of the Canal in 1825, all began a new era for Michigan. Between 1830 and 1837 the population soared from 31,000 to 87,000.

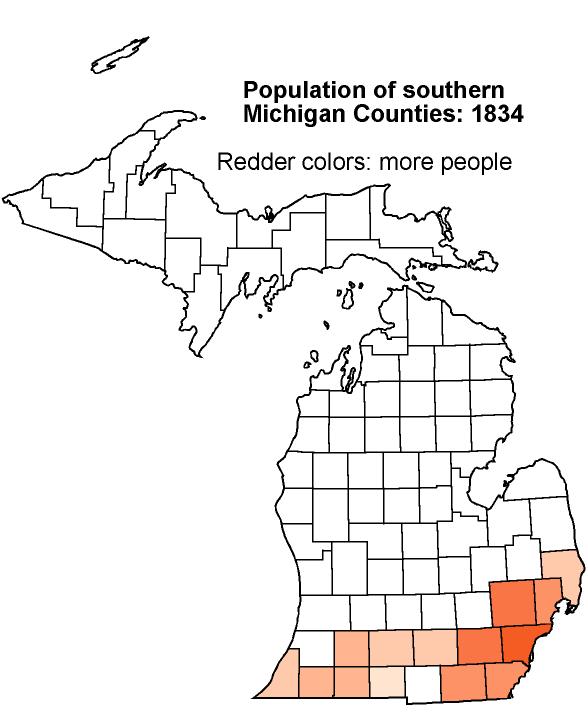

The Michigan frontier of the 1830's was confined to only about 25 of the state's present 83 counties. It did not reach much further north than the four southern tiers of counties. North of a line drawn through Muskegon and Bay City, the pinelands begin, and underneath the pines the soil is thin and sandy. Furthermore, the growing season is markedly shorter. Hence, pioneers seeking new farms by-passed northern Michigan and moved on into Wisconsin and Iowa. They neglected Michigan's Upper Peninsula for the same reasons. One writer on the West states that by 1848, when a great tide of immigration from overseas began, "Michigan was so well integrated that much of this influx was forced to jump over into Illinois, Iowa, and Wisconsin." Just what he means by his statement that Michigan was "well integrated" in 1848 is obscure. The census of 1850 shows that over 98 per cent of the state's population at that date lived in the southern counties of the lower peninsula comprising about one-quarter of the state's total area. Only 7,649 people were counted in an area of the north approximating the size of the state of Indiana. There obviously was abundant public land left in Michigan, but its quality was such that it could not compete for settlers with the more fertile lands further west, where the climate was less severe.

The southern third of the state was, thus, settled first. It was the first portion surveyed and included some of the best farmland in the state. In addition, the Chicago Road, the Monroe Pike, and other transportation arteries provided easy access from principal entry points such as Detroit. A majority of the early pioneers were New Englanders. These settlers found that the small prairies and oak openings of southern Michigan were well adapted for wheat, and wheat and wool eventually became the state’s principal cash agricultural products. People arrived in such numbers that between 1820 and 1834, the population increased tenfold. By the time Michigan was about to become a state, Michigan Territory had become the most popular destination of people moving west.

The Upper Peninsula’s more limited agricultural potential was not tapped until the mid-1800s. As the area’s fledgling lumbering and mining industries drew more and more people to the region, agriculture was introduced to provide food for the new arrivals. It was found that many crops, particularly hay and potatoes, did well in the rigorous northern climate.

In the meantime, after the opening of a land office at Detroit in 1818, public lands were selling fast. With vast optimism, towns were platted in the wilderness, and mineral and timber lands were surveyed and leased with a lavish hand. Quarter sections aplenty were being taken up by the early 1830s when "Michigan Fever" officially began and with it, brought on a sudden boom in Michigan’s population. Public land sales rose from 147,062 acres in 1830 to 498,423 in 1834. By 1835, the $2,271,575.17 realized on the sale of 1,817,248 acres in Michigan represented 1/7 of the national totals. Land sales at the Detroit office in 1834 had averaged $1000 a day in the first seven months of that year, but by 1835 the Monroe office had taken in $147,000 by June 30. By the fall the increased interest in the western part of the territory pushed monthly sales there up to the $200,000 range.

Source: Unknown

Previous to 1820 the price of public lands at the Land Office was $2.00 per acre, on the

installment plan, 50 cents down and 50 cents per year. In 1820, due to the "cost and

difficulties of collecting arrears" and "to check speculation," the policy

was changed to that of the sale in 80 acre plots at $1.25 per acre, for cash.

The boom peaked in 1836, when sales of approximately 1/9 of

Michigan’s total land area---4,189,823 acres---brought in $5,241,228.70. This was a

record year for land sales in any state or territory. The relatively undeveloped areas of

western Michigan received the most attention, with sales at the Kalamazoo land office

representing nearly 40% of the territorial totals for 1836.

Much of the activity by 1836 was generated by speculators, not by those

who intended to settle in the territory. Land was especially attractive to those who had

money to invest, and in the mid-1830's land in Michigan was regarded as the hottest item

on the market. How much Michigan land was purchased for speculative purposes at this time

can probably never be precisely determined, but that the figure certainly did constitute a

sizable percentage of all the public land sold.

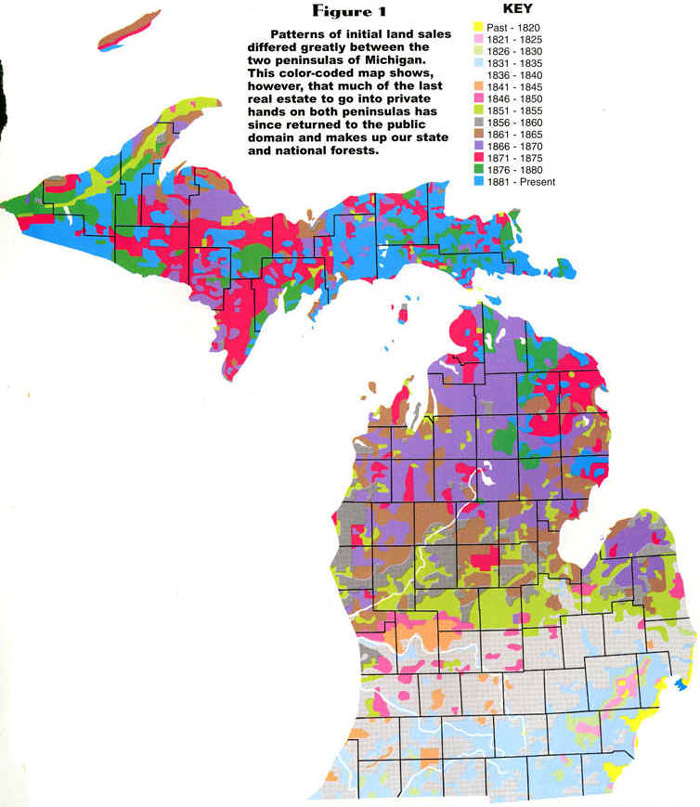

The map below is one of the best compilations ever made of land sales

and their changing "geography". The maps tracks land sales across the

state in great detail, and is worth spending some time examining.

Source: Unknown

Nevertheless, the population census figures for the 1820's and 1830',

which reveal an almost equally spectacular growth rate to those for land sales,

demonstrate that Michigan’s land resources were attracting a great number of

permanent settlers as well as nonresident speculators. In 1820 the federal census had

listed 8,765 person in Michigan Territory, including a handful of residents of what is now

Wisconsin and Minnesota. By 1830 the population had increased to 31,640. This included the

persons residing in the region west of Lake Michigan, but at least 29,000 were living in

what would become the state of Michigan. In the next four years the population almost

tripled. When Michigan had achieved statehood in 1837, another census indicated that the

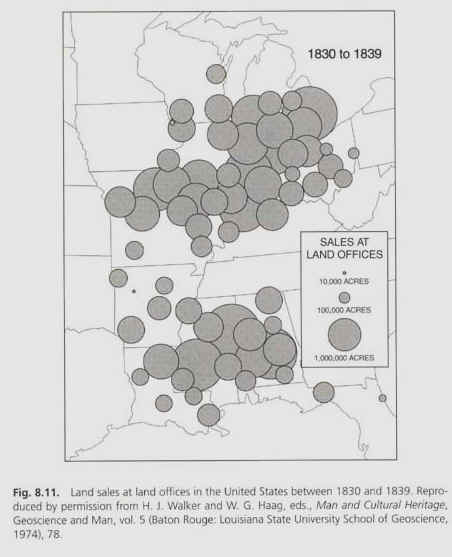

population was 174,543. The map of "Land Sales" in the US between 1830 and

1839 (below) illustrates the popularity of Michigan as a destination for settlers at this

time.

Source: Unknown

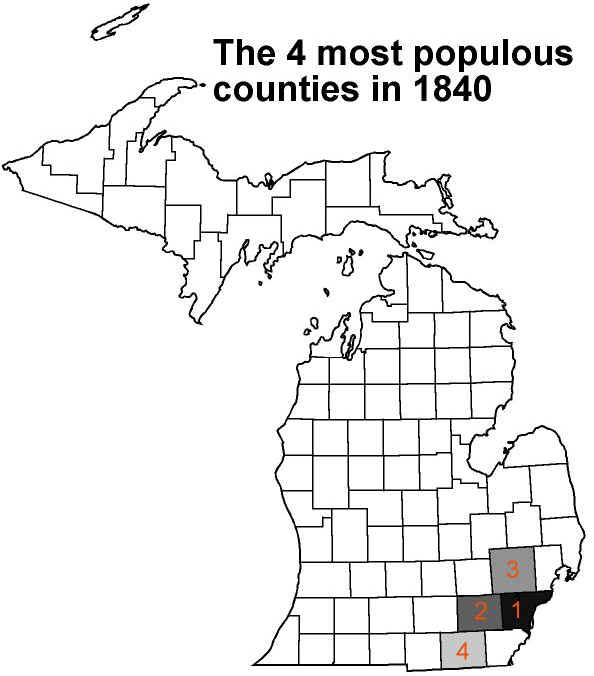

The spread of settlement in Michigan may be judged by the establishment of counties.

When a considerable number of settlers had bought land in a given area, the territorial

legislature generally provided them with a county government.

Source: Michigan State University, Department of Geography

By 1837, when Michigan was admitted into the Union, 38 counties had been established,

including all those in the four southernmost tiers with the exception of Barry.

An important segment of Michigan’s 1837 population came from the

neighboring states of Ohio and Indiana. These people settled mainly in the Detroit area

and in St. Joseph, Cass, and Berrien counties. Many of them had been born in Virginia and

North Carolina. In and around Detroit and Monroe, the French-Canadian influence was still

observable in 1837; French was still spoken by many persons.

Here and there throughout the territory were colonies of settlers representing distinctive

nationality or religious groups. Generally such settlers clustered together in a

neighborhood, and a number of them came into Michigan together as a community. For

instance, there were numerous German colonies in Shiawassee and Washtenaw counties, a

"Pennsylvania Dutch" colony in Cass County, Irish settlements in Kent County and

the Irish Hills area of Jackson and Lenawee counties, the

latter also the site of one of several Quaker colonies in Michigan. Overall, the

proportion of foreign-born appears to have been slight. The number coming from below the

Mason-Dixon Line also was small. The pioneers were predominantly Protestant in

religion, the main exceptions being the Irish and some of the Germans.

Over 13% of the state�s inhabitants in 1837 lived in

Wayne County. Detroit accounted for about 9,000 people. The rural parts of

Wayne County were less thickly populated than those of neighboring counties.

But the changing character of Michigan�s economy and of Detroit�s importance

as a result of those changes is seen in Detroit�s sharply reduced proportion

of the area�s population as most settlers moved into the interior, searching

for farming opportunities. Whereas in 1810 about a third of the territory�s

non-Indian population was located in Detroit, by 1840 only one of every 23

non-Indian residents of the state lived there. Washtenaw County, with an

essentially rural population, was a close second to Wayne County in 1837,

with 21,817 residents. Not far behind was Oakland County, just north of

Wayne County, while to the southwest, Lenawee County, another essentially

rural, agricultural county, was fourth in population.

Source: Michigan State University, Department of Geography

Go to Michigan Fever Part 2

This material has been compiled for educational use only, and may not be reproduced without permission. One copy may be printed for personal use. Please contact Randall Schaetzl (soils@msu.edu) for more information or permissions.