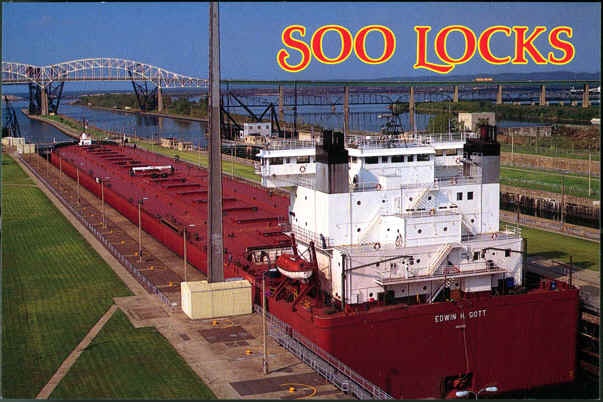

THE SOO LOCKS

Postcard

All of the boat

traffic that flows into or out of Lake Superior must move through the

locks of the St. Mary's River, at Sault Ste. Marie. The St. Marys River is

the only water connection between Lake Superior and the other Great Lakes.

There is a section of the river known as the St. Marys Rapids where the

water falls about 21 feet from the level of Lake Superior to the level of

the lower lakes. This natural barrier to navigation made necessary the

construction of the locks project known as the St. Marys Falls

Canal.

The world-famous

Soo Locks form a passage for deep-draft ships around the Rapids ("Sault")

in the St. Marys River. The "Soo Locks" have the distinction of

being the busiest locks in the world.

Here are some facts about the

locks:

Water not flowing through the locks or down

the St. Mary's River nearby is diverted into a canal, and the drop in head

is used to generate hydroelectric power. The U.S. Hydroelectric

Power Plant located north of the locks generates over 150 million kilowatt

hours of electrical power each year. The first priority for the use of the

power is for operating machinery at the Soo Locks. The surplus is

purchased by a private power company and is distributed to homes and

businesses in Sault Ste. Marie and surrounding

communities.

The entire facility at the St. Marys

Falls Canal is operated and maintained by the Corps of Engineers, US Army

Engineer District, Detroit.

The Poe Lock has the

largest capacity of the four locks. The lock, completed in 1968, took six

years to build and is the only lock ever constructed between two operating

locks.

Inspection of the locks themselves, the

culverts, and galleries is done periodically to check the structural

soundness of these areas. This inspection is normally done during the

winter months.

Many different types of vessels pass

through the locks during a year, varying in size from the small passenger

vessels and work boats to large ships carrying more than 72,000 tons of

freight in a single cargo. In recent years, the number of passages through

the locks has averaged about 12,000 per year, down from previous years due

to the larger vessels being able to carry more

freight.

The channels through the St. Marys River

have been deepened to permit ship loading to a maximum draft of 25.5 feet

at low water. When lake levels are above the low water datum, the larger

ships load to take advantage of the deeper water at a rate of over 200

tons per inch of additional loading.

Postcard

How do the locks (and indeed, all locks) work? View this

animation to see. It's really quite simple--just a matter of

closing and opening some gates. No pumps are involved.

After the ship is in the lock, water is allowed to

flow in and raise the ship up (if it is travelling to the higher

lake--Superior) or water is allowed to flow out and lower the ship (if it

is traveling to the lower lake--Huron). Then the doors are simply

opened (see below) and the ship moves on its way. Traveling through

the US side of the locks is free to all ships.

A TRIP

THROUGH A LOCK:

Ships travelling from Lake Huron to Lake Superior must

enter the locks as shown below. Note that the water level is low in

the lock (you can tell this because the walls of the lock are exposed, not

filled to the brim with water). The lock doors are open, and the

ship sails in. You are looking north.

Source: Photograph by Randy Schaetzl, Professor of Geography - Michigan State University

Now, once in the lock, the doors

close and water begins to pour into the lock. Turn around on the

ship and see--the image below (looking south) shows the lock doors closing

so the ship can be raised up to the level of Lake Superior. Note

again how much of the doors is exposed--a clue that the water is low in

the lock and that it is at the level of the lower lake--Huron.

Source: Photograph by Randy Schaetzl, Professor of Geography - Michigan State University

Once the water level in the lock has been raised to that of Lake

Superior, the doors are opened and the ship sails out, into the higher

lake. The image below is what such a ship would see in that

situation. The view is to the north, into Lake Superior.

Source: Photograph by Randy Schaetzl, Professor of Geography - Michigan State University

In the aerial view below, one can see the four sets of locks, and a

freighter moving through, into Lake Superior. Note that, in two of

the locks, the water level is lowered, allowing boats from Michigan-Huron

to enter.

Source: Unknown

History of the Locks

Before white men came to the area, the Ojibway Indians who lived nearby

portaged their canoes around the rapids to reach Lake Superior from the

St. Marys River. The image below is from 1850.

Source: Unknown

The falls

(or rapids) of the St. Mary's River were a common "stopping point" for

Indians. The falls often served as a trading point, or perhaps a place to

meet and exchange stories. It also was a great fishing spot

(especially for Whitefish) for the Native Americans (and still is...see

the image below).

Source: Unknown

The

spring catch of Whitefish was crucial to their health and livelihood, as

at the end of winter their food supplies were scarce, and their need for

quality protein was high.

Early pioneers arriving in the territory were

also forced to carry their canoes around the rapids. When settlement of

the northwest Territory brought increased trade and large boats, it became

necessary to unload the boats, haul the cargoes around the rapids in

wagons, and reload in other boats.

In 1797, the

Northwest Fur Company constructed a navigation lock 38 feet long on the

Canadian side of the river for small boats. This lock remained in use

until destroyed in the War of 1812. Freight and boats again needed to be

portaged around the rapids.

Congress passed an act

in 1852 granting 750,000 acres of public land to the State of Michigan as

compensation to the company that would build a lock permitting waterborne

commerce between Lake Superior and the other Great Lakes. The Fairbanks

Scale Company, which had extensive mining interests in the upper

peninsula, undertook this challenging construction project in

1853.

Building the locks in the 1850's was a major

engineering project, since large amounts of solid rock had to be

moved. The images below show part of the construction of the locks,

and an early view of the locks.

Source: Unknown

In spite of adverse conditions, Fairbanks

completed a system of two locks, in tandem, each 350 feet long, within the

2 year deadline set by the State of Michigan. On May 31, 1855, the locks

were turned over to the state and designated as the State Lock. The

canal had opened on schedule in June 1855, but its cost ran three times

the estimate, at just under $1,000,000.

An important date: JUNE 22, 1855. The passage of

the steamer Illinois through the locks at Sault Ste. Marie marks the

opening of unobstructed shipping between Lakes Superior and Huron. Ships

are no longer forced to stop at Sault Ste. Marie and portage their cargoes

around the rapids of the St. Mary's River, which drops twelve feet from

Lake Superior to Lake Huron. The canal is the result of a long-sought 1852

grant by Congress to Michigan of 750,000 acres of public land.

Construction, begun in mid-1853, has progressed despite cost overruns,

food shortages, a hostile climate and a cholera epidemic. The mile-long

canal and two 350-foot locks arranged in tandem have been completed in two

years. The Sault locks provide new impetus to Michigan's fledgling

mining

industry. Copper

mining on the Keweenaw Peninsula began in the early 1840s, and

Michigan led the nation in copper production for many years. In 1844

surveyor William A.

Burt discovered iron ore deposits near Negaunee.

Iron ore mining

expanded gradually, but by the late nineteenth century Michigan produced

more iron ore than any other state. Michigan also produced significant

amounts of salt, gypsum, oil and natural

gas.

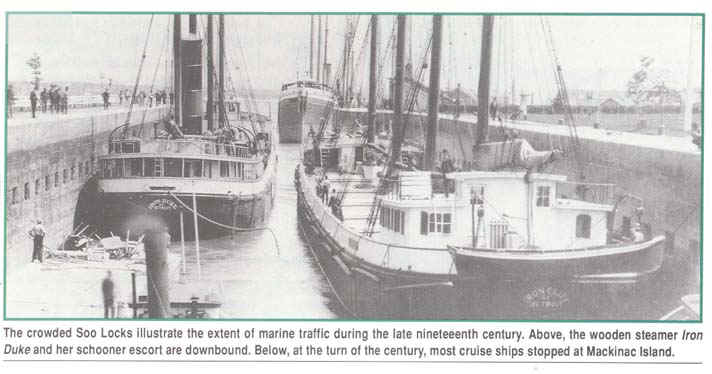

Boats

which passed through the State Lock (picture below) were required to pay a

toll of four cents per ton, until 1877, when the toll was reduced to three

cents. Within a few years, commerce through the canal had grown to

national importance, and the need for new locks became clear. The funds

required exceeded the state’s capabilities, and thus, in 1881 the locks

were transferred to the United States government under the jurisdiction of

the US Army Corps of Engineers. The Corps has operated the locks, toll

free, since that time.

The opening of the canal, named the

Michigan State Locks, but eventually called simply the Soo Locks,

perfectly coincided with the increased demand for iron as railroads

expanded westward. Between 1850 and 1860, the railroad network in the

United States nearly quadrupled in size. The new locks expedited the

shipment of much-needed iron ore to steel mills in the southern Great

Lakes. In return, investment capital flowed north to the Lake Superior

region, expanding mining operations and improving transportation

arteries.

Source: Unknown

The first load of iron ore through

the Soo Locks amounted to 132 tons in August 1855. Total ore tonnage that

year was 1,447. During the 1860 shipping season 120,000 tons of ore passed

through the Soo Locks. One century later the total volume of downbound

iron recorded at the Soo exceeded 100 million tons.

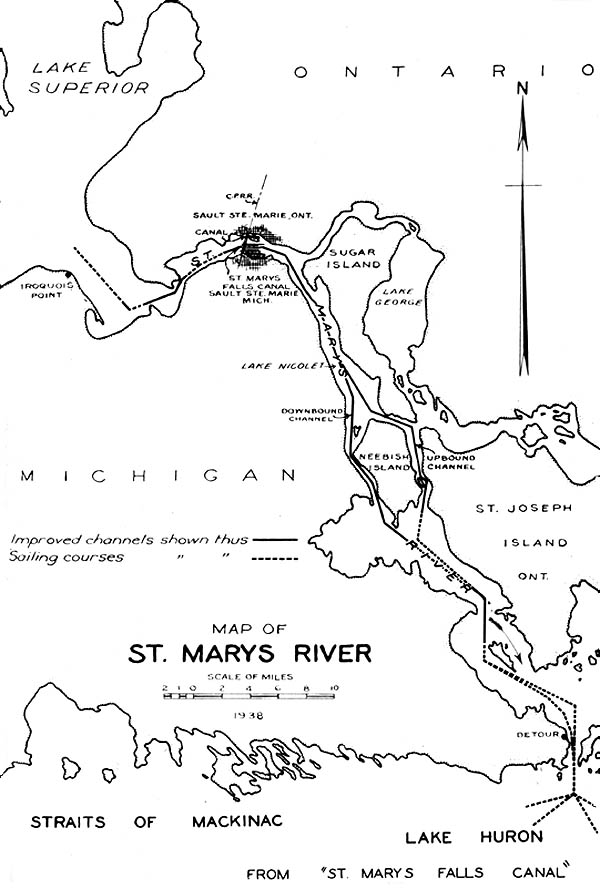

The falls of the St. Mary's River, where today exist the Soo Locks seen above, are present because of a resistant sill (layer) of rock within the river channel. The map below shows that area of the river and its main islands in 1938.

Source: Unknown

The Soo Locks during World War II

During World War II, the fear of axis attacks on the Soo Locks was extremely prevalent throughout the United States. Although far from the European and Pacific theater, the Soo Locks played an important role during World War II, due to the large amounts of iron ore being transported on large barges through the locks. 90% of America’s iron ore during this time was shipped through the Soo Locks to be transported to steel mills and then factories to build war machinery, such as tanks, planes, and munition.

The fear of a homeland attack in America grew as the war waged on, and with the growing importance of the Soo Locks and iron for the war effort, military protection of the Soo Locks was critical. By 1942, large numbers of troops were sent to Sault Sainte Marie to protect the Soo Locks, making it one of the most guarded places in the United States during World War II. The militarization of the Soo Locks was so large that Fort Brady-a military fort built in Sault Sainte Marie to guard against British invasion from Canada- was so full, there was no room to house all the military personnel.

The military defense tactics were very extensive. Defenses included land, air, and sea to protect the Soo Locks from foreign attacks. Air defenses including searchlights to patrol the sky were added, and defenses against possible torpedo attacks were put in place.

During 1942 an order for construction of a new lock was put into place. This lock would allow larger barges to transport larger amounts of iron ore through the Soo Locks. The new MacArthur lock was completed soon after orders in 1943, allowing larger freighters to pass through. The name of the new lock which replaced the previous Weitzel Lock was named after Douglas MacArthur, a five-star general in the Pacific theatre of World War II.

Due to the lessening threat to the Soo Locks by Axis powers during the war, military security was lessened in 1943. The Soo Locks were never attacked during World War II despite the fear of foreign threat.

Today, the Soo Locks are still responsible for 90% of America’s iron ore transportation. The Soo Locks are still known as a military target, but security for the Soo Locks has decreased significantly since World War II.

This material has been compiled for educational use only, and may not be reproduced without permission. One copy may be printed for personal use. Please contact Randall Schaetzl (soils@msu.edu) for more information or permissions.