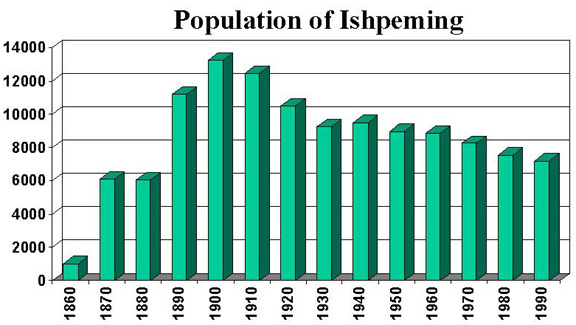

ISHPEMING AND NEGAUNEE: BOOM/BUST TOWNS?

The cities of Ishpeming and Negaunee, located a few km west of Marquette on US 41, are

today small, sleepy towns with a great deal of history, and many old, tattered houses and

buildings. In the late 1800's, when iron mining was at its peak in the area, they

were much larger cities.

Source: Michigan State University - Department of Geography

It all started with the discovery of iron ore near Negaunee in 1844.

Negaunee and Ishpeming are located in the Marquette Iron Range.

Negaunee's first cabin was erected in 1846. Nine years later there were only six

houses in Negaunee. In 1855, 11 years after the ore was first dicovered, a visitor

noted, "very little in the way of amusement" in the town. Wolves, he said,

could be heard howling at night. By 1871, a village had finally emerged from where

previously had been tall trees and 4-foot deep mud. Visitors noted that the mud, in

1871, was now only a foot deep. It must have looked something like this:

In the late 19th century, American industry faced a labor relations

crisis--partly engendered by the growing size of business and the increasing economic and

social gap between employers and employees. Between 1880 and 1900 the United States

suffered 23,000 strikes. Many of these confrontations turned violent. To try to combat

labor discontent, some employers responded with harsh repression, hiring spies and armies

of security personnel to break strikes and intimidate workers. Labor, in response, turned

to revolutionary ideologies, vandalism and armed confrontation. In an attempt to find a

middle ground between these extremes, many corporations between 1880 and 1920 turned to paternalism.

Paternalism involves providing employees with company-controlled

amenities that are not required by law or negotiated contract, such as low-cost housing,

health care and recreational facilities. Through paternalism employers attempt to

influence the attitudes and morals of their employees and attract, maintain and control a

peaceful and reliable labor force.

Paternalistic practices were especially common in areas where workers

could not easily acquire privately offered goods and services. Thus, it is not surprising

that the isolated Michigan iron-mining companies, located throughout the sparsely

populated Upper Peninsula, were heavily involved in paternalism. Paternalism in

Michigan’s iron-mining regions began, however, not as a corporate weapon to quiet

worker discontent and combat unionization, but as business necessity. Michigan’s

Upper Peninsula was a cold, forbidding wilderness during much of the nineteenth century.

In summers its large, numerous swamps bred hosts of insects, making life miserable; in

winters it was frozen in by ice and snow. There were virtually no roads, and so getting

goods into the mining areas was expensive, if not impossible.

Paternalism in the UP iron mines was a give-and-take. The mines

provided cheap housing, garden plots where their employees could grow vegetables,

electricity, and even water. In many cases all these amenities cost the miners less than

$10 per month and much of that money was in bills that were not US currency but iron mine

currency---good only at the local iron mine store.

Married miners were rented individual houses, such as the row houses shown below, while

single miners lived in boarding houses. Company stores provided for most of the

"wants" of the miners, and in many cases were the largest stores within miles.

In return, the content miners were less likely to strike and to call for higher wages.

With the fall of the mining industry, people have left and the populations of these two

"boom towns" has fallen.

With the eclipse of mining interests in Michigan at the turn of the century, the

wealthy financiers moved west to the iron fields of Minnesota, but the immigrants stayed

on in the peninsular society largely created by their presence. Thus, iron towns like

Negaunee, Ishpeming, Marquette, and Escanaba continued to exist despite the number of

dying towns and rusting blast furnaces.

The hills below show the region near Ishpeming, in the heart of the

Marquette Iron Range, during the mid-20th century. This era was chosen because trees do

not block the view of the iron-rich hills. Today, regrowth of forest has

occurred. The hills are composed of iron-rich rocks like diorite, and other

"iron formations".

This structure is the shafthouse of the Cliffs-Shaft mine, in Ishpeming, one of only two iron mines in the city proper. By the turn of the century mines in Ishpeming were producing more than 2 million tons of ore per year. Shaft mines like this one were extremely prosperous and productive during the early 20th century.

Mine workers such as the ones shown below were the backbone of the mines. Six days a week of back-breaking labor in the mines fueled the industrial revolution of the United States and satiated the demand for iron that was growing almost daily.

Source: Photo courtesy of Michigan History Magazine

Source: Michigan State University - Department of Geography

This material has been compiled for educational use only, and

may not be reproduced without permission. One copy may be printed for personal

use. Please contact Randall Schaetzl (soils@msu.edu)

for more information or permissions.