Executive summary on salt mining: Salt is produced as brine and as rock salt. Initially, salt production centered around some brine wells in the Thumb area. An excess of wood products at the time (late 1800's) provided the raw materials required to "dewater" the brine. When the lumber industry fell off, so did the salt brine industry. Those old wells simply drew the brine up, and evaporated the water. Today, all brine operations inject steam or hot water into dry salt beds and extract the brine.

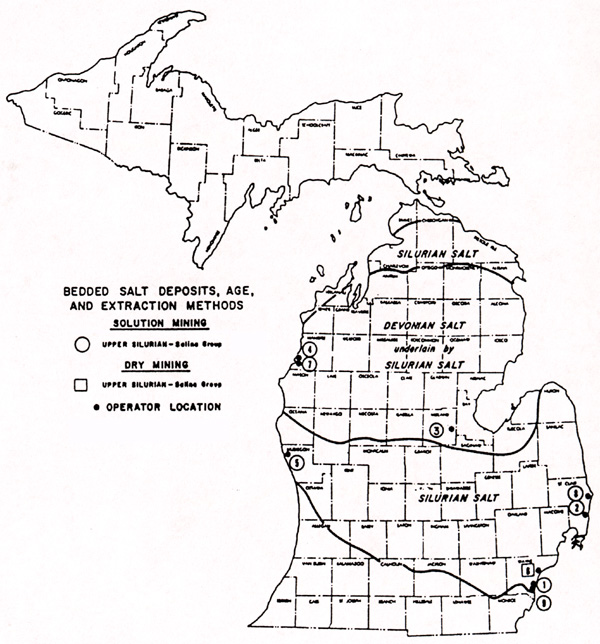

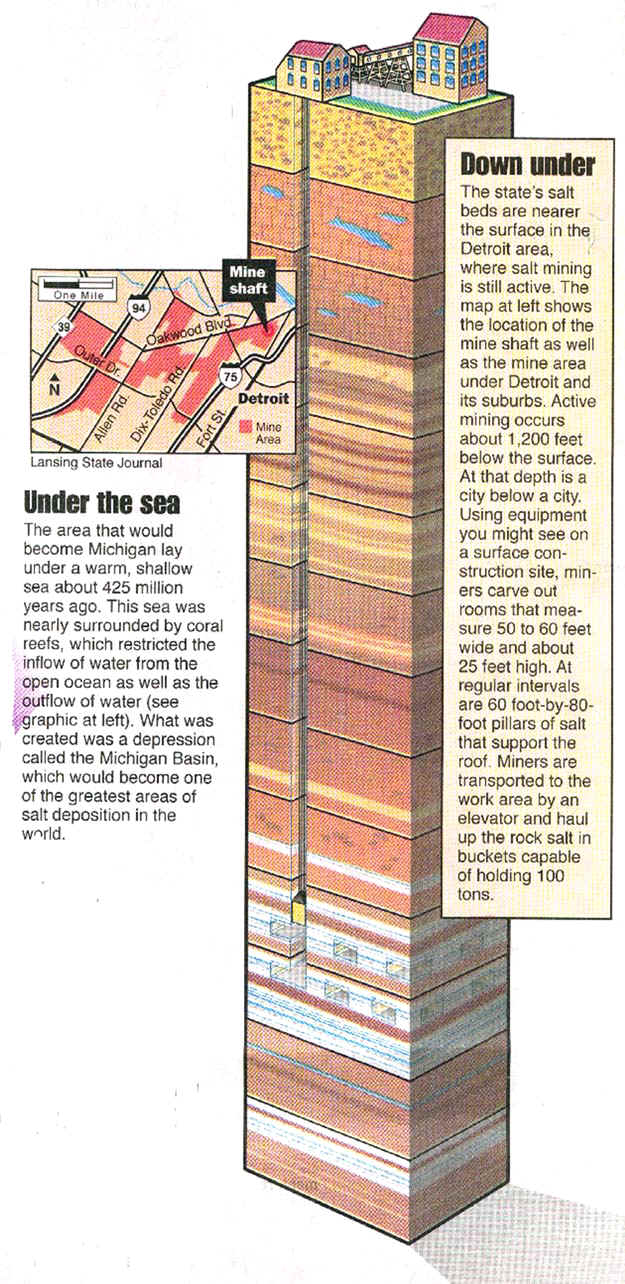

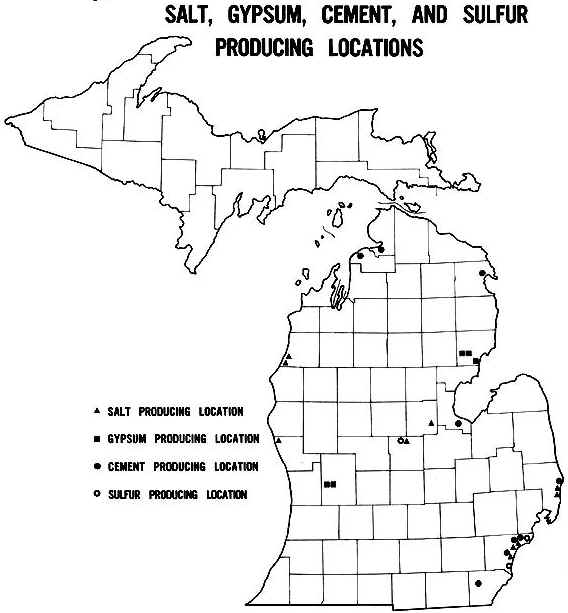

Halite salt (NaCl) can be mined in two different ways: as a solution or in dry mining (see map below). In solution mining, fresh water is injected through a pipe into deep shafts that end in the salt beds, and salty water (brine) is drawn upward and dried, to recrystallize the salt. Or, salty brine found in shallow wells can simply be pumped to the surface and dried there, to make salt. In dry mining (below), the salt is mined in large underground caverns, much like one would mine coal or iron ore. Dry mining is only practiced in the Detroit area. Salt worth millions of dollars comes (or at least used to come) from underneath Detroit each year. But not a pinch of it goes on a boiled egg. Glistening and white under southwestern Detroit, are rock salt mines totaling over 100 tunneled miles. Hundreds of tons a day were once lifted a quarter of a mile to the surface.

Source: Detroit Free Press

The greatest rock salt production in the U. S. is obtained from the

Michigan, Ohio, and Ontario. In 1958 the salt production from these areas amounted to 8.7

million tons or 35% of the combined total produced in the U. S. and Canada. The image

below, from a salt mine, shows a vertical "wall of salt" about a little over a

meter in height.

Source: Photograph by Randy Schaetzl, Professor of Geography - Michigan State University

Three important factors lie behind the location and development of the Detroit salt mining

area:

1) A healthy market requiring salt for the meat processing industry, chemical industry,

water softening snow and ice removal from roads and highways.

2) Abundant salt at a reasonable depth and of sufficiently high quality to permit

economical mining,

3) The availability of low cost water transportation on the Great Lakes which facilitates

the movement of salt in Canada from eastern Saskatchewan Province to western Quebec

Province, and in the U. S. from the "Dakotas" to western New York State.

A radical change in salt production occurred in 1906 when the Detroit Salt and

Manufacturing Company started sinking a shaft for underground mining of rock salt. In 1913

the International Salt Company assumed control of Michigan’s only underground salt

mine. As recently as a few years ago, miners at this mine, one of the world’s largest

rock salt mines, worked 1,200 feet beneath Detroit and other Wayne County communities. The

mine, which consists of 100 miles of tunnels, has never experienced a collapse or mine

fatality. For years it produced tons of rock salt daily, most of which is used for ice

control. Today it is closed.

Source: Unknown

Mining

The geology of the Great Lakes salt mining area consists of sedimentary

deposits of shale, limestone, sandstone, dolomite, gypsum, anhydrite, and rock salt

(halite). These formations within the mining area are relatively continuous and generally

undisturbed by faults or other forms of sharp ground movements. The Salina Group

actually consists of a number of individual salt beds separated by layers of shale,

dolomite, and anhydrite. The salt beds themselves contain bands of anhydrite which vary in

thickness from 1/6 in. or less to several inches. The anhydrite (calcium sulphate) content

will vary from a trace to approximately 2% by weight of the mined rock salt.

The top of the Salina Group of the Eastern Salt Basin varies in its

vertical distance below the surface. For example, under Michigan the formation varies from

a minimum of approximately 800 ft to a maximum depth of approximately 6800 ft, while the

top of the formation under Ohio, near the West Virginia boundary, reaches a maximum depth

of approximately 6000 ft. This variation in depth is in part attributed to a gradual

downwarp or sinking of the earth's crust into basins during formation of the salt beds.

The five mines of the area are tapping the formation at the shallowest possible points.

Source: Detroit Free Press

The room and pillar method of mining is employed in all salt mines

in Michigan, Ohio, and Ontario. The rooms vary in width from 30 to 60 ft and in height

from approximately 17 to 40 ft. Pillar size is adjusted so that the extraction or recovery

will attain a maximum of 70%. Actual mining is confined completely to the salt bed.

Therefore, usually a minimum of 1 ft of salt is left on the floor, while 4 to 6 feet of

salt is left to form the roof. Generally speaking, the absence of gas, water, excessive

dust, and the presence of sound roof and ribs as well as comfortable temperatures of 55�

to 75� F, permit working conditions in a salt mine to be excellent.

A comparison of the maps above and below will show that the main salt dry mining sites in

Michigan are located in Detroit, while solution mining takes place along Lake Michigan and

along the St. Clair River. The biggest salt dry-mining operation in Michigan today

is in Wayne County. The Detroit Salt Company produced the first salt there in 1895.

Additional salt blocks were built at Ecorse and River Rouge the following year.

Solution mines are often called "brine mines".

Source: Unknown

Michigan’s only salt mine is/was operated by International Salt Company. The

miners here have mined out an area 22 feet high for about 300 acres. Officials drive about

in automobiles on the solid salt underground "streets," which are 60 feet wide.

In the mine, the temperature is between 56 and 60 degrees in all season. The Company pumps

100,000 cubic feet of fresh air a minute down one shaft. Unlike a coal mine, the operation

is free of the hazards of water and gas. The room-and-pillar system is used to take out

the salt. Rooms from 50 to 60 feet wide are driven out and blocks of salt of the same

width are left for roof support. Workmen "undercut" the walls of salt with a

machine that bites out a channel at the floor. Then holes are drilled in the wall from

floor to roof. At night, the holes are loaded with dynamite and the blasting operation

sends the wall of salt crumbling down. Electric shovels dip the salt into trailers the

next morning. Trucks powered by electricity take it to a giant crusher underground.

Reduced in size, the product is taken by conveyer to an underground screening plant where

the various sizes are separated. Again by conveyer, the salt is taken to the larger shaft

where it is lifted in nine-ton buckets.

The biggest development in the industry in recent years is increased

use of the product for highway purposes.

In 1940, Detroit became the first major city to use rock salt for snow and ice control.

Other cities followed. The Detroit mine now supplies Michigan and several other states,

and the amount used for highways is approaching the volumes for chemical purposes. Highway

uses include the tons mixed with road bases to make for greater density and lower the

freezing point to reduce cracking. The images below show what road salt looks like when it

is crushed into a form that is "road ready". Note that parts of the road

salt are dark, reflecting the thin "muddy" seams in the salt (see the images

higher up in this page).

Source: Photograph by Randy Schaetzl, Professor of Geography - Michigan

State University

Source: Photograph by Randy Schaetzl, Professor of Geography - Michigan

State University

Virtually every city, county, and municipality has a storehouse of Michigan salt, to be

used on roads in winter. This one is a small storage shed of salt for the Meridian

Mall, Okemos.

Source: Photograph by Randy Schaetzl, Professor of Geography - Michigan

State University

The estimates of salt deposits in Michigan are astronomical. In the

Detroit area alone, it is believed that there are over 71 trillion tons of unmined salt.

Geological studies estimate that 55 counties of the Lower Peninsula cover 30,000 trillion

tons of salt. But like much of Michigan’s mineral wealth, only a fraction of this

salt can be economically recovered.

Some of the images and text on this page were taken from various issues of Michigan History magazine and from C.M. Davis’ Readings in the Geography of Michigan (1964).

This material has been compiled for educational use only, and may not be reproduced without permission. One copy may be printed for personal use. Please contact Randall Schaetzl (soils@msu.edu) for more information or permissions.