LIMESTONE MINING

Calcite and dolomite, when heated and in some cases slurried or combined

with salt, are used in making many everyday products such as paper, glass,

paint and varnish, soap and detergents, textiles, refractories, baking powder,

and pharmaceuticals, including milk of magnesia and bicarbonate of soda.

Finely ground, they are used to control coal mine dust, to collect sulfur

dioxide from power plant exhaust, to sweeten soils, and as ingredients in

fertilizer and stock feeds, to name a few. Limestone is used extensively

in Michigan to refine beet sugar. When

burned in a kiln to drive off gases, calcite and dolomite form burnt lime.

Among the uses for burnt lime, in addition to steel

making, are water and sewage treatment, acid waste neutralization, and

road base stabilization. Crushed calcite and dolomite are used in concrete,

road construction, building materials, and as a filler in asphalt.

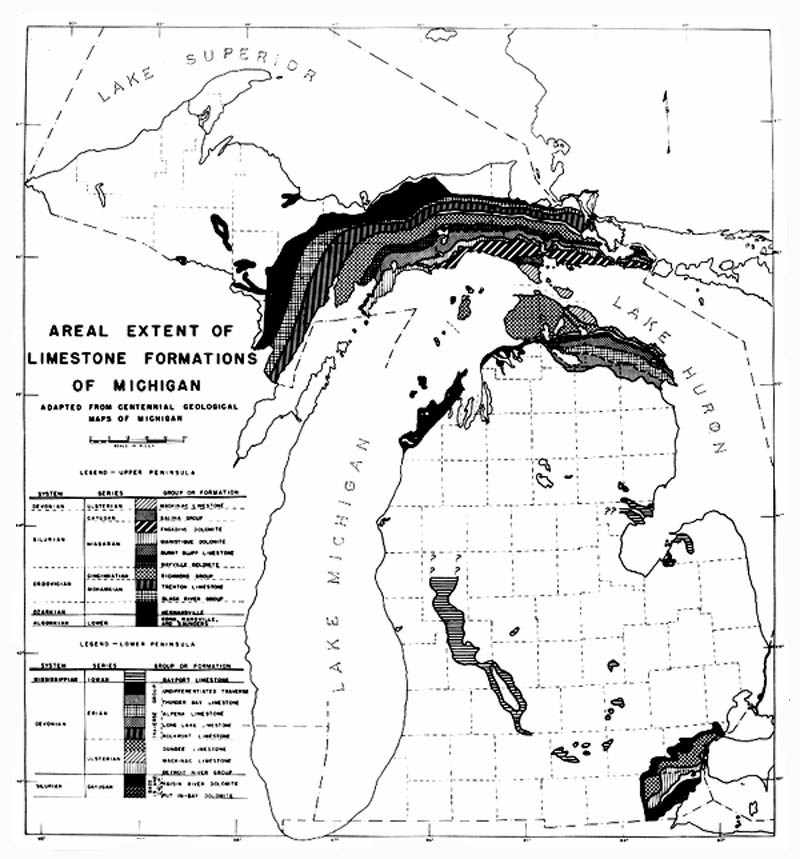

The map below shows the locations in Michigan where limestone and dolomite (a magnesium-rich

limestone) are located. In actuality, these rocks are found beneath all of

lower Michigan and the eastern UP; this map only shows those locations where

limestone would be the FIRST rock you'd hit in a well. That is, the map shows

where limestone is the uppermost bedrock. Note that limestone outcrops are

found primarily along the outer margins of the Michigan basin.

Source: Unknown

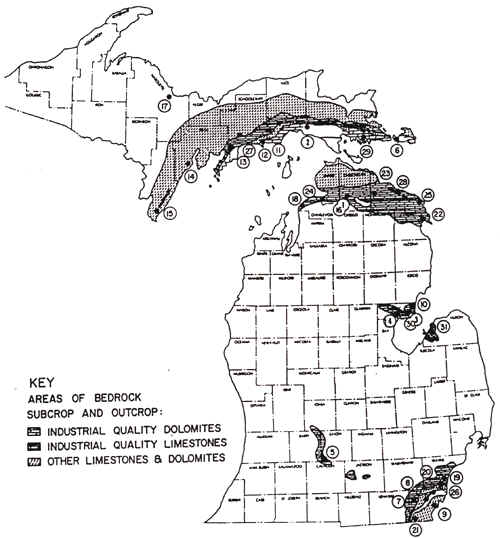

Now note the map below, which shows the locations of industrial-quality

limestones and dolomites. Notice that most of the high quality limestones

and dolimites are in the NE lower peninsula and the southeastern UP.

Fortunately, both areas are near the Great Lakes. Why is that important?

Read on.

Source: Unknown

Source: Unknown

Compare the above maps to the map below, which shows where limestone

is mined or excavated. Notice that the mines are located near major transportation

arteries, or on the Great Lakes proper. This is because these rocks,

like many rocks, are so heavy that they do not bear the cost of transportation

well. That is, they have a low value/weight ratio; such products either

cannot be moved very far from where they occur (or are manufactured), or

they must be transported by very inexpensive means, such as large freighters.

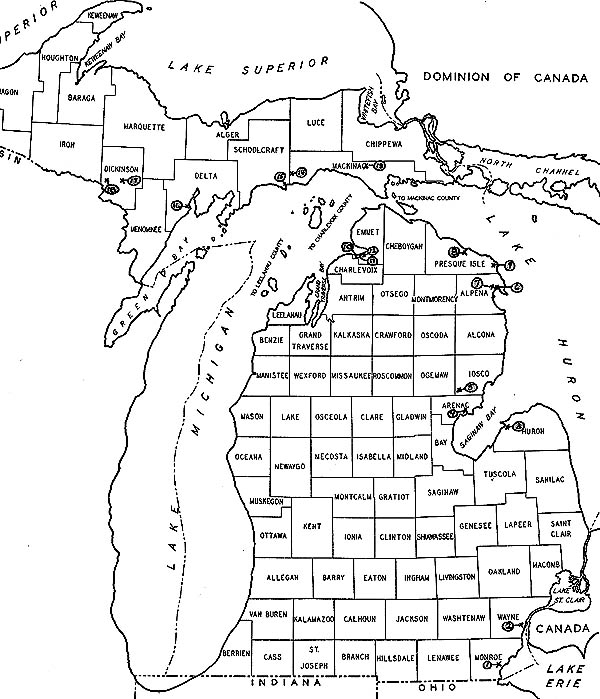

LIMESTONE QUARRIES OR MINES IN MICHIGAN, AS OF 1939

Source: Unknown

The quantity of limestone that Michigan produces has generally been steady

throughout the years, while the number of quarries has decreased. Have

a look at the map below, which shows that there are really only three major

quarries left in the state, but each of these is LARGE.

Limestone Quarries in Michigan, as of 2003

Port Dolomite

· Located in Cedarville, MI

· Produces dolomite and limestone

· Ships from 3 to 4 million net tons per year

Port Inland

· Located near Gulliver, MI

· Produces both high calcium carbonate limestone and dolomite

· Ships 3 to 4 million tons per year

Port Calcite

· Located in Rogers City, MI (Presque Isle County)

· Worlds largest limestone quarry

· Produces high calcium carbonate limestone

· Ships from 7 to 10.5 million net tons per year

The next series of images depict various means by which limestone

is quarried or processed, beginning with the oldest technologies and continuing

up to the present.

Below is an image of an old lime kiln, in which raw limestone (CaCO3) is

converted to CaO, or lime. Lime has many more uses, especially in the chemical

industry, than does limestone. Lime is a mineral made

by heating limestone or dolomite in a kiln. Lime is used in a variety of

chemical industries, in sugar processing plants, in steel mills, sewage treatment

plants, and at paper mills. "Burned" or kilned limestone was

also used as plaster and mortar in the homes of early settlers, and even

into the mid-20th century. This is one of the larger kilns of its day, which

was circa 1900.

Source: Unknown

In the years following 1900, new uses have not only resulted in the utilization of Michigan limestones on a gigantic scale, but also in a demand for limestones with special characteristics that meet the exacting specifications of the different types of use. Consequently, closer and closer attention has been paid to the physical and chemical qualities of the stone quarried. Most of the chemical uses of limestone, and these are by far the most important, require the stone to be as nearly pure and high in calcium content as possible. Michigan is fortunate in having large deposits of very pure, high calcium stone in the northern part of the state, some of which are conveniently located on or near the shores of the Great Lakes. Thus, quarries were opened in these deposits early in the 20th century. As the competitive advantages afforded by the cheap water transportation possessed by the water front quarries became evident, interior quarries (far from the Great Lakes) were later abandoned. This has resulted in the eventual concentration of the major part of the Michigan production in a few large highly mechanized quarries operated in the rich and extensive lake side deposits. Because of their suitable location and high quality, and because of other factors favoring quarry development, these deposits have come to produce stone for use not only in Michigan, but in the entire Great Lakes region.

Below you can see the remains of a small kiln, used to turn limestone (CaCO3) into lime (CaO), by heating it up and driving off the CO2). Small kilns were often located right at the minesite, reducing transportation costs, since the raw stone did not need to be moved far, and the processed lime weighed substantially less than did the raw material.

Source: Unknown

Lime (as opposed to limestone) has long been a valuable commodity in Michigan,

as the chart below shows:

Source: Unknown

The stones below were quarried for building stone, and then left behind. Many buildings in NE lower MI are made of limestone.

Source: Unknown

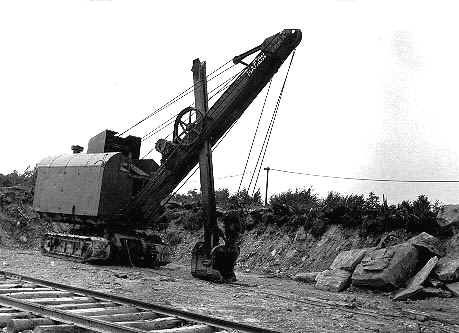

The electric stripping shovel below was used in the 1950's to remove the

overburden, usually glacial deposits, from the stone before further excavation

could begin.

Source: Unknown

Below, two carloads of limestone await transport to the rock crusher. Large cars such as these were typical of limestone mining operations in the mid-20th century.

Source: Unknown

This old photo provides a good example of a mine, located far from the lakes, which was opened early because it had high quality limestone and thin overburden, reducing quarrying costs. However, because it was not near a Great Lake, transporting the low value, heavy stone to markets was too costly, and the mine soon closed.

Source: Unknown

Below is a photo of a steam shovel loading limestone onto a railroad car. Transporting stone and aggregate by rail was an economical alternative for mines not located near the Great Lakes.

Source: Unknown

Later on, the size of the excavating equipment grew and grew. This large electric shovel could load more stone with one scoop than a person could in one day.

Source: Unknown

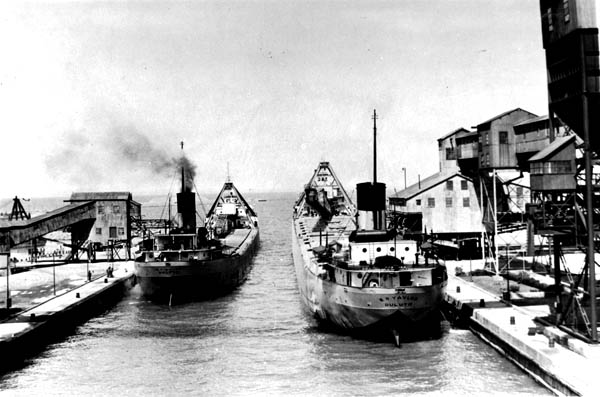

The most economical way to move limestone long distances was by boat. Here, two large freighters are ready to be loaded.

Source: Unknown

Below is a typical loading dock. Limestone was moved by belt to the docks, and then dumped down the large "chutes" into the cargo holds of the Great Lakes' freighters. Docks like these are still commonplace today.

Source: Unknown

Note how the Calcite limestone quarry (below) is located on Lake Huron for

easy access to ore boats.

Source: Photograph by Randy Schaetzl, Professor of Geography - Michigan

State University

Note also (below) that stone and sand are the number one commodities moved

by freighters on the Great Lakes.

Source: Unknown

Source: Unknown

Source: Unknown

The map above shows the locations of limestone quarries in the state.

Note the quarry at Bayport (inner part of the thumb). Here, the famous

Bayport Limestone is quarried. The pictures below show that quarry,

and beach rip rap, which is one use of the limestone. Most of the limestone

is transported from this quarry by truck, but some is still moved by rail.

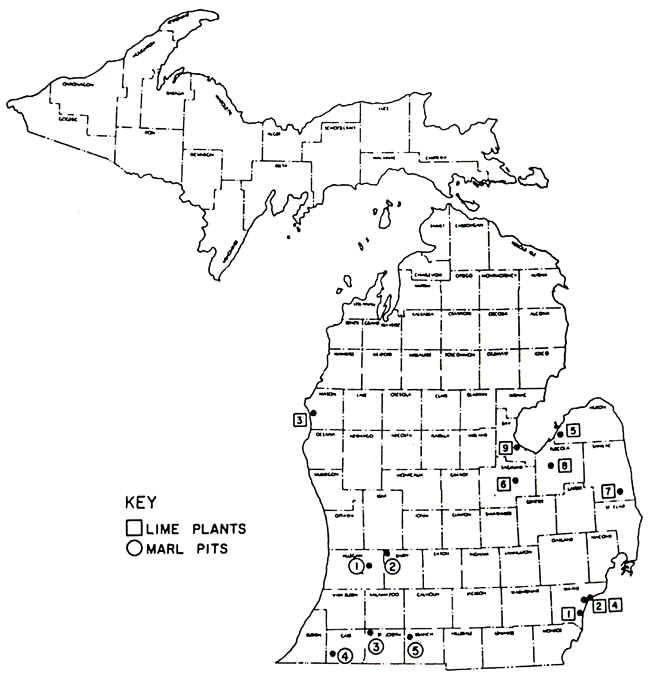

In addition to limestone, Michigan also produces pure lime

as well. Lime is purified limestone, and is often of more value to

industry than is limestone. The map below shows where lime is produced.

Some of the lime comes from marl--limey ooze that was depoisted on the bottoms

of lakes, often glacial lakes.

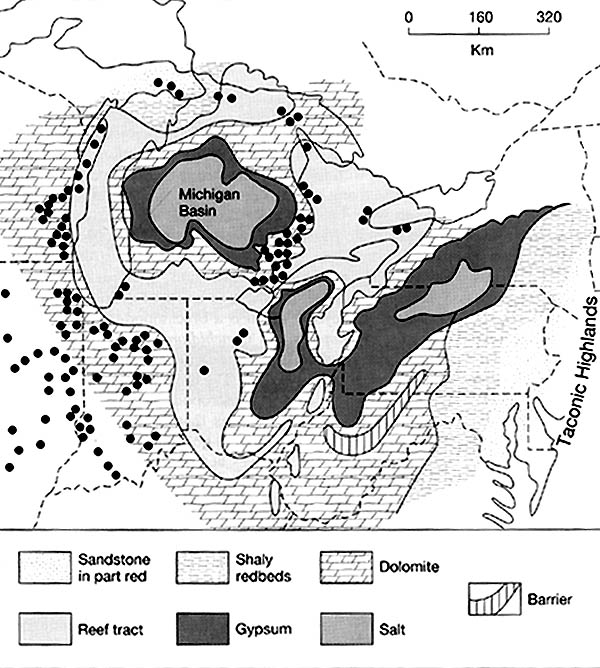

The map below shows the North American Silurian reef system. The dots represent

Silurian reefs. During the mid-Silurian, pinnacle reefs surrounded the edges

of the Michigan basin. Each reef extended up, vertically, from the sea floor,

some 200+ meters. They commonly are up to a km in width. Today, these reefs

are important oil and gas "traps", and because the limestone in them is so

hard and pure, the reefs themselves (when close to the surface) are important

sources of limestone. The large quarry on the south side of Chicago, the

Thornton Quarry, is crossed by I-94; perhaps you have driven across it! While

these reefs were forming, limestone and dolomite was precipitating in the

deeper waters of the basin. In the deepest water, salts and gypsum were precipitating

out in sedimentary beds.

Source: Unknown

Today, Devonian outcrops in Wayne, Charlevoix, Emmet,

Cheboygan, Presque Isle, and Alpena Counties are quarried for limestone and

dolomite. These rocks are then used for flux in steel mills, as agricultural

lime and in sugar refining. They are a large resource in the production of

cement, crushed stone, in the chemical industries; in glass and paper manufacture;

for water softener, gas purifier, and for construction purposes. To

make Portland cement, clay, shale and

limestone is ground to a powder and baked in a kiln. The baked mixture forms

clods (clinkers), which are then ground up and mixed with gypsum. Most of

the raw materials are mined in open pits. Michigan traditionally ranks in

the top five states in terms of cement production. One of the largest cement

plant in the state is in Alpena.

Crushed stone

Most crushed stone is limestone and dolomite. It is used mostly for construction

purposes, although much of it is also used in shoreline protection. In construction,

crushed stone is used as an aggregate in concrete mixes. The stone binds

the mix together when it hardens. Almost 60% of all crushed stone is used

as aggregate in highway concrete and asphalt. All crushed stone in Michigan

is mined in open quarries. Drilling and blasting are necessary. Crushing

is done at the quarry. The crushed rock is screened. Most of the larger stone

quarries are located near the shores of Lake Huron-Michigan, in the northern

lower peninsula and the UP. Locations on the Great Lakes facilitate shipping

of the stone, since it is a high weight low value commodity.

The largest limestone quarry in the world is in the Rogers City and Dundee

limestone near Rogers City, Presque Isle County. For many years the "fines",

or waste rock for which no use was known, were dumped into Lake Huron. Now

they are being recovered and used in the chemical industries and for agriculture.

Source: Photograph by Randy Schaetzl, Professor of Geography - Michigan State University

This material has been compiled for educational use

only, and may not be reproduced without permission. One copy may be

printed for personal use. Please contact Randall Schaetzl (soils@msu.edu)

for more information or permissions.