The Great Lakes, interconnected by rivers, straits, and canals, together form one of the world's busiest shipping arteries. The lakes are linked with the Atlantic Ocean via the St. Lawrence River. Since the completion in 1959 of the St. Lawrence Seaway, a system of dredged channels, canals, and locks, the lakes have been open to medium-sized oceangoing vessels.

Several other important channels facilitate commerce on the lakes. Lake Erie is connected with the Atlantic by way of the Erie Canal and the Hudson River. Lake Michigan is connected with the Mississippi River and the Gulf of Mexico by way of the Illinois Waterway, which encompasses the Chicago River, the Chicago Sanitary and Ship Canal, the Des Plaines River, and the Illinois River. The Sault Sainte Marie Canals allow ships to pass around the rapids in the Saint Marys River between Lakes Superior and Huron, while the Welland Ship Canal connects Lakes Erie and Ontario, bypassing Niagara Falls. Between 50 million and 100 million metric tons of freight pass through these channels each year; the lakes and channels are closed to shipping between December and April, when ice could impede passage.

Specially designed long narrow vessels carry most of the freight on the lakes. Historically, the Great Lakes have been a major route for shipment of iron ore from Minnesota, northwest Ontario, and Labrador (an area including northern Qu�bec and the mainland portion of Newfoundland) to steel-producing plants in the lower lakes region, especially the Chicago and Gary, Indiana, area; Detroit; Cleveland; Erie, Pennsylvania; and Hamilton, Ontario. However, iron production in Minnesota has declined in recent years, as has steel production in areas bordering the southern portions of Lakes Michigan and Erie. Therefore, ore transport on the lakes has declined significantly. However, it is still the largest single cargo shipped on the lakes.

Grain grown in the Great Plains is another important cargo. It is shipped principally from Duluth, Minnesota, to ports on the lower lakes and to foreign markets via the St. Lawrence Seaway. Coal, limestone, petroleum products, and general cargo make up most of the rest of the cargo on the lakes. About 10 to 20 percent of the freight shipped from Great Lakes' ports passes through the seaway to the Atlantic.

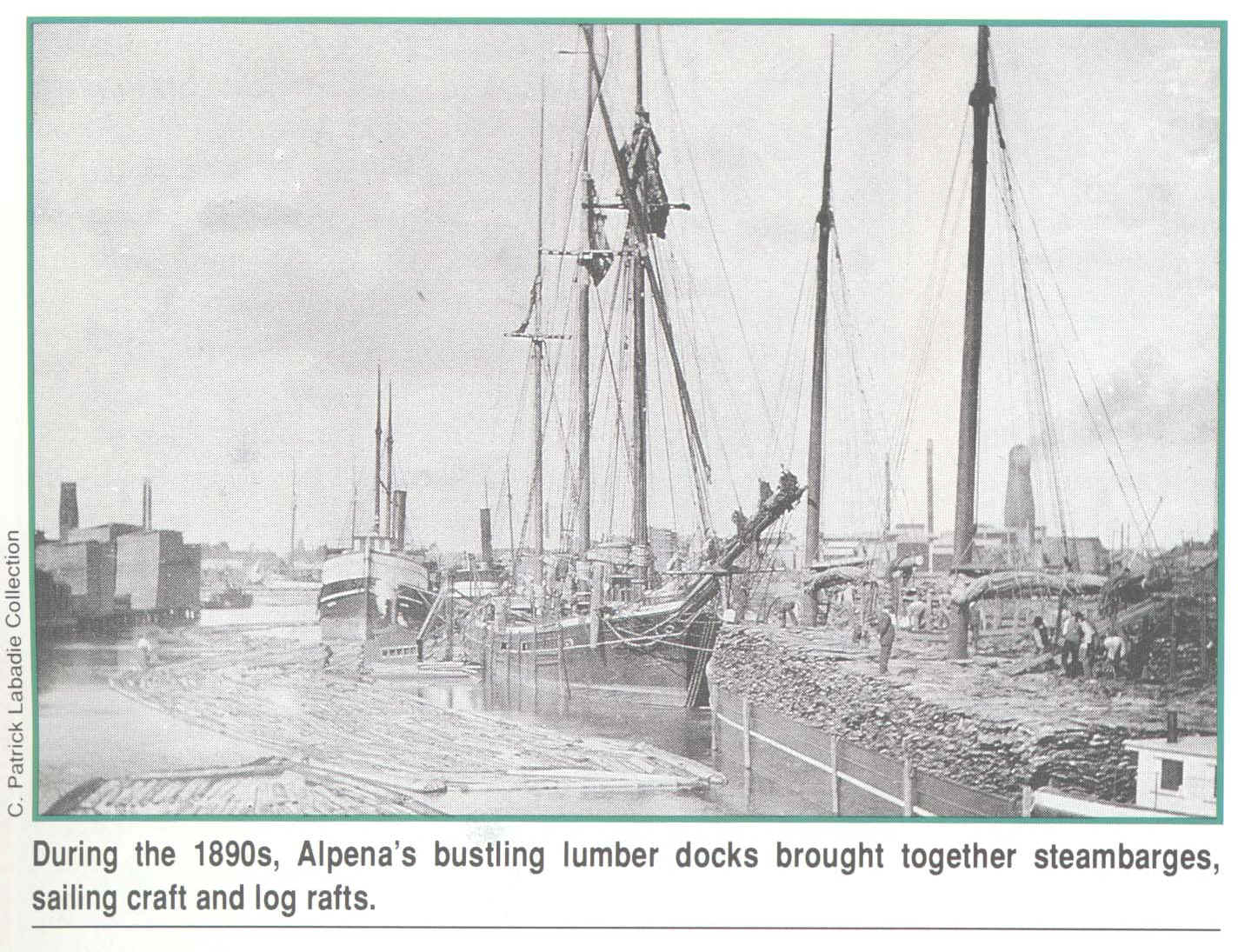

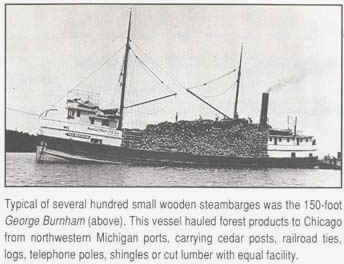

Moving materials by ship on the Great Lakes has long been economical,

especially for bulky cargo like ore, rocks, and wood. Such cargos

can be moved long distances quite economically, if done so on water.

Source: Encarta

Source: Encarta

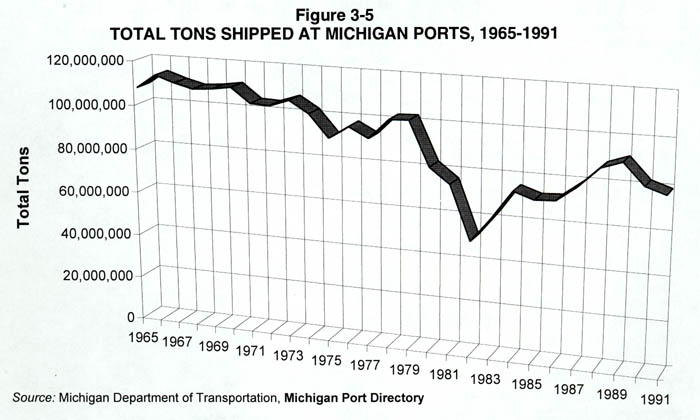

The bulk of the tonnage shipped on the Great Lakes is raw materials used

for manufacturing. Such commodities include stone, ores such as iron ore,

and cement. These commodities are very heavy, and therefore necessitate

that they be transported in vessels that can move large quantities of

heavy materials cheaply. Moving commodities such as these that have a

low value/weight ratio is easily done by water. The chart below is a reflection

of the cargoes on the lakes as of 2000.

Source: Unknown

Most of Michigan's and Minnesota's iron ore is eventually carried in "super

carriers", each capable of carrying 60,000 tons or ore. In 1989, iron ore pellets

accounted for 27% of the waterborne cargo on the Great Lakes.

The position of the Great Lakes as bulk carrier routes between the ore and limestone resources of

the upper lakes and the coal of the lower lakes has been a principal factor in the

location of the American steel plants. The ore traffic was the most important reason for

construction of the Soo locks. With the depletion of high grade

ore in the lakes area it may be that the most important function of the St. Lawrence

seaway will be to open the lakes to foreign ore rather than to carry out products of

industry.

Parts of this page are from the Encarta Encyclopedia: www.encarta.msn.com and from data published by the MDOT.

This material has been compiled for educational use only, and may not be reproduced without permission. One copy may be printed for personal use. Please contact Randall Schaetzl (soils@msu.edu) for more information or permissions.