The odor coats the towns of Bay City, Caro, Sebewaing, Croswell and Carrollton - a dusty, slightly musty, faintly sweet yet earthy aroma, like steamed broccoli but without the tang. Obnoxious only in its omnipresence, it’s the smell of money, according to everyone from the CEO of Monitor Sugar Company to an administrative assistant at the Michigan Sugar Company’s Caro plant. It’s the smell of the sugar-beet processing plant, a noisy, magical place where homely sugar beets are transformed into pure white sugar crystals, the fuel of America The sweet smell of sugar-beet processing has been strong in Michigan for more than 100 years.

A bit of history...

A century ago some two dozen factories peppered Michigan. At that time, sugar-beet factories sprang up across Michigan from Benton Harbor to Ann Arbor and up to Charlevoix. The majority of the plants were centered in the Saginaw Valley and the Thumb area, where the remaining factories still operate.

Although Michigan’s turn-of-the-century sugar-beet boom was the beginning of the industry as it stands today, its roots stretch back to the late 1830's, when White Pigeon farmer Lucius Lyon tried his hand at sugar-beet cultivation with seeds from Germany. A small sugar-beet factory was constructed, but operations ceased in 1840 after months of frustration from poor cash flow and rudimentary processing methods.

During the 1880's as forested land disappeared due to uninhibited harvesting of the timber resource, investors eyed sugar beets as another source of income. Joseph Seaman, co-owner of a Saginaw printing company, saw the vegetable’s potential during visits to Germany, where sugar-beet production thrived. Dr. Robert C. Kedzie, a chemistry professor at Michigan Agricultural College (present-day Michigan State University), initiated statewide testing of the beets using the seeds that Seaman brought back from Germany. Kedzie was later dubbed "Father of the Michigan Beet Industry" by the first Michigan Sugar Company board of directors. Stump land, the painfully apt description of former forests, was prime property for pioneer sugar-beet farmers armed with Kedzie’s seeds.

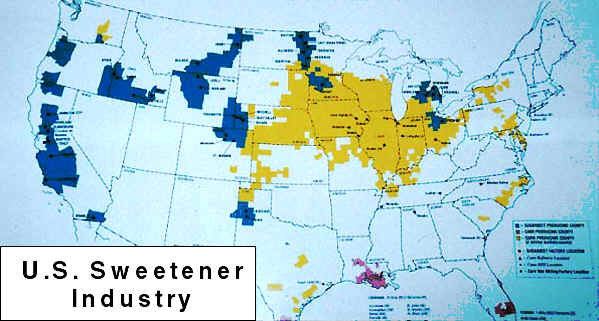

Although the map (below) is slightly hard to read, it makes an important point about the kinds of sweeteners we use in the USA, and where they are grown. Sugar cane, a tropical grass with sweet, sugary juice in its stalks, is grown in Florida, southern Texas, and Hawaii (red on the map). Sugar beets, grown in areas shown in blue, are concentrated in the north, primarily because storing the beets after harvest is easier in cool climates. Beets provide an important sweetener for mid-latitude states and nations. Michigan sugar (under the Meijer, Pioneer and other local brands) comes primarily from sugar beets. Lastly, corn syrup, made from corn kernels, is becoming the sweetener of choice for many kinds of foods such as soda. Wherever corn is grown (yellow areas), high fructose corn syrup can be an important byproduct.

Michigan has nine million plus people and has more demand for sugar than all the sugar

manufactured in the state. Are we dangerously sucrose-addicted consumers? No. The demand

comes from large manufacturers like Kellogg, Lifesavers and Post and from Michigan cherry

producers.

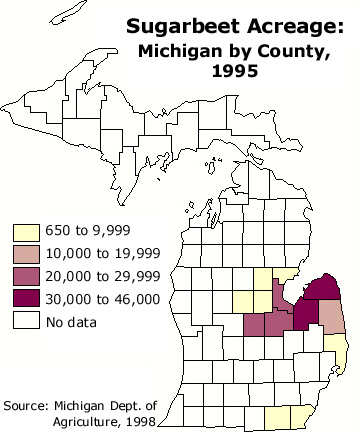

In Michigan, the main beet-growing areas are on the flat, clay soils of the Saginaw and Erie lowlands.

Processing Beets into Sugar

Although you can’t make a silk purse out of a sow’s ear, you can convert the

homely, humble sugar beet into refined white sugar. In a process that has remained

relatively unchanged during the past 100 years, grubby, pale sugar beets are transformed

into the granules we pour into our morning coffee.

During harvest in the fall, producers use a machine called a rotor beater to cut off the

tops of the beets, which are left in the field. The removal of the foliage is called

"topping". A sugarbeet lifter/loader then lifts the beets out of the soil

onto a truck, and the beets are delivered to a receiving station at the sugarbeet

processing plant. Harvested sugarbeets are very heavy – an average stack of beets

weighs about 40,000 tons. The beets are then trucked to a receiving station or to

one of Michigan’s processing plants. As those living on the east side of the state

know, during autumn the odd sugar bet appears along roadways, a large grayish white road

hazard startling in its resemblance to a big rock.

Sugar beets are dug by large mechanical harvesters and taken by truck to processing facilities. In Michigan, beets are typically dug in late October.

This truck will drive directly from the beet field to the processing plant, with its load of sugar beets.

The Factory Process

Sugar beet processing factories are scattered throughout the thumb, with plants in Caro, Saginaw, and Bay City, to name a few. At the plant, the beets are piled into large stacks; processing takes place until February.

The sugar beets stay in the trucks until they arrive at processing plants like the Michigan Sugar company’s Caro plant, where they are dumped in water-filled flumes and separated by their buoyancy from rocks gravel and even an occasional fence-post shaft. More than four thousand tons of beets rumble through these flumes each day during a typical campaign, which runs twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week, from September through February or March. In the factory, the beets are first cleaned in a beet washer to remove most of the soil and stones. Some 60 tons of stones removed daily from the flumes are sold to landscapers or crushed for roads.

Next the beets are pumped to the beet washer, which cleans away mud and sand and contains a magnet to remove metal bits. Freshly washed, the beets jiggle down toward the slicers, oblivious of their imminent fate. Through the slicers they go, and below the machines a conveyor belt marches out the sliced beets or cossettes, that resemble cottage (french) fries, or a cross between shoestring potatoes and ridged potato chips. Michigan Sugar’s four plants have daily slicing capacity of 16,150 tons, or beets from roughly two hundred thousand acres of farmland. This process "opens" the beet up and allows the sugars within to be readily extracted. The beet "noodles" (cossettes) are sent through a machine called a diffuser or extractor. Hot water is mixed with the beets to dissolve and remove the sugar from the beet noodles.

Source: Photograph by Randy Schaetzl, Professor of Geography - Michigan

State University

At this point in the process, science kicks in. The beets disappear into a diffuser.

Through osmosis, sugar is extracted from the cossettes that are immersed in hot water. The

beet pulp is squeezed, dried and formed into pellets to be sold for livestock feed and pet

food. The water and sugar juice are saved, and this solution is called "raw

juice". Impurities in the raw sugar juice are removed by mixing the juice with

milk of lime treated with carbon dioxide gas. From this carbonation process, the product

next goes to the Olivers, where the lime cake "mud" is separated from the juice.

This mud is then pumped to the factory’s lime pond, where it will sit until ready to

be spread on farmland. Michigan Sugar’s Caro plant sends an average of 60,000 tons of

lime to sugar-beet farmers each year.

The beet noodles, now free of most of their sugar, are dried into beet pulp for

livestock feed. The raw juice is treated with lime (CaCO3) and carbon dioxide gas to clean

the mixture again. It is sent through a big, round filter to clean it and remove other

non-sugars. The raw juice goes into a series of big tanks called evaporators where some of

the water is boiled off. At this point, the mixture contains more sugar than water. It is

a thick-like syrup and is again filtered to make sure it is very clean. During the loud

roaring and rumbling ‘round-the-clock campaign, breakdowns are never a minor problem.

In fact, according to Caro plant administrative assistant Lisa Wagner, she’s not

known the process to stop for repairs. When one piece of machinery fails, "the guys

can turn it off and keep the process going. It’s amazing to me how they keep

everything going."

The mixture passes through a big tank called a white pan, which allows the thick juice to

boil at a low temperature. After the dried pulp and lime cake have been removed, the next

step is evaporation. Sugar beets are primarily water and the excess must be removed in a

series of evaporators. Boiled under vacuum, the juice flows from one evaporator to another

until a heavy syrup, which is filtered once again, remains. In the crystallizers, the

syrup is boiled, stirred and cooled, and crystals begin to form. At this point what began

as sugar beets becomes massecite, a syrupy liquid containing the grit of crystallization.

On the pan floor, sugar continues boiling under vacuum and takes on the consistency of

fudge. Workers, once known as sugar tramps, keep track of the product through

computer readings, touch and taste. The heavy liquid heads to the centrifugals, where

machines whirl the sugar at 1,200 revolutions per minute and dry it with filtered, heated

air. The syrup exits through minute holes in the centrifugals, leaving pristine white

sugar crystals. The remaining bitter syrup is molasses, a product used in the manufacture

of citric acid, antibiotics, yeast and other products. As for the pure white stuff, from

here on out, it’s a matter of packaging the product and shipping it out. The whole

process, if you were to follow one beet, lasts four to five hours.

All of Michigan's sugar beet processing plants are in the Thumb area, as the one as

Sebewaing (below).

Source: Photograph by Randy Schaetzl, Professor of Geography - Michigan

State University

Some of the text on this page has been taken from an isue of Michigan

History magazine: SWEET SMELL OF SUCCESS by Laura Bennett-Kimble

This material has been compiled for educational use only, and may not be reproduced without permission. One copy may be printed for personal use. Please contact Randall Schaetzl (soils@msu.edu) for more information or permissions.