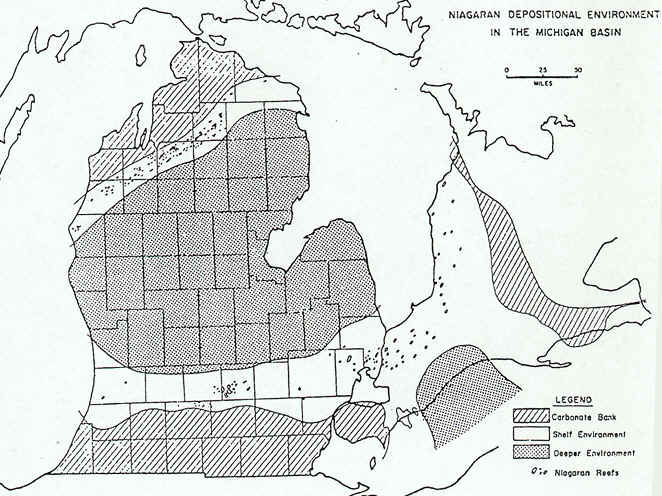

Limestone is a sedimentary rock composed of animal shells and chemical precipitates with a large component of CaCO3 in them. Limestones usually form in deep ocean waters. In the Michigan basin, limestones formed at many different times, when the basin was filled with water of varying depths. Below, the environment of deposition during Niagara time (when a lot of dolomites were forming in the Michigan Basin) is illustrated.

Source: C.M. Davis, Readings in the Geography of Michigan (1964).

The history of limestone formation is told nicely below, in this text

passage from a book on the Geography of Michigan: Even in these early warm seas

another force was at work building rocks. In some way, the first bacteria and one-celled

plants learned to take lime (CaCO3) from the water; they collected in

jelly-like masses. Lime collected on these early plants, layer upon layer, and built up

into great masses of limestone. Later, when animals came upon the earth they were also

one-celled creatures living in the sea, but as they struggled for existence they evolved

to more complex creatures, and in time they also took lime from the sea water to make

protecting external coverings or shells. When these creatures died their shells fell to

the sea floor, accumulated in thick masses, were also broken to lime muds, but all in time

became limestone rock – the cemeteries of the animals which lived in the seas, and

the museums in which the records of past life (fossils) are preserved.

Gradually, as the Paleozoic seas deepened, almost 2/3 of the North

American continent was submerged. As the Ordovician period began in Michigan, the

shoreline probably pushed farther northward, as we find traces of early Ordovician

limestones in Houghton County. The rock and fossil records show us that this time lasted

for 70 million years. At first the seas were deep and clear, a situation which is

conducive to the deposition of lime muds, and the eventual formation of limestone. These

muds were laid down on the sea floor, which became the graveyards of millions of shelled

creatures that lived in the first of the Ordovician seas. Gentle earth movements, or

perhaps climatic changes, later caused the late Ordovician seas to be alternately shallow

and muddy, or deep and clear, thus the sediments of the late Ordovician became shales and

limestones. The Ordovician-aged Trenton limestone supplies building material and crushed

stone for road building and fresh water. It is a source of petroleum in the southern part

of the Southern Peninsula and potential source of oil within the basin.

Again the seas deepened, genial climates set in, the seas were warm and clear. A new

period, the Silurian, set in. Algae and bacteria precipitated lime brought to the sea in

solution by clear streams, millions of shelled creatures swam about, corals built long

coral reefs, and great thicknesses of lime muds were built up. Over 1600 feet of Michigan

limestones are Silurian in age. The thickest and perhaps the hardest of these are the

rocks we term Niagaran.

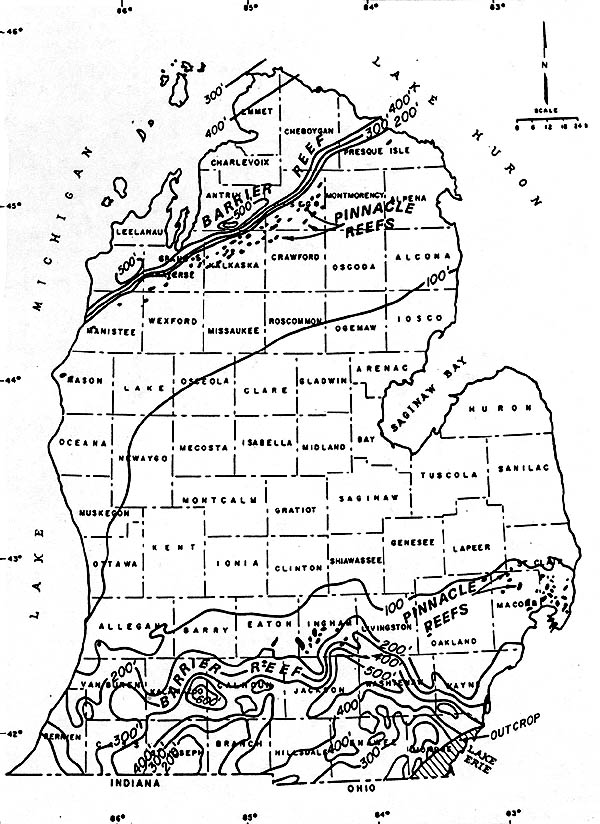

One of the interesting mechanisms of formation of limestone in the Michigan basin are the limestone (coral) reefs that formed. Petoskey stones are a type of coral, now turned to limestone. These reefs existed as barrier reefs and as pinnacle reefs. Barrier reefs occurred in the shallowest of water, and are a continuous, near-shore feature. Pinnacle reefs form in deeper water, as isolated "pinnacles" of coral. Note how, in the map below, the barrier reefs are farther from the center of the peninsula (basin), while the pinnacle reefs are more "basinward".

Source: C.M. Davis, Readings in the Geography of Michigan (1964).

The drawing below shows a cross-section through the reefs, as they would have formed in a Paleozoic sea. The pinnacle reefs formed farther offshore, and were eventually "buried" by more carbonate rocks at a later time.

Source: C.M. Davis, Readings in the Geography of Michigan (1964).

If you would like to see what these coral reefs were like, you can find

beautiful fragments of them in the stone piles of Chippewa, Mackinac, Schoolcraft, and

Delta Counties: chips from the Niagara limestone that comes to the surface (outcrops) from

Manitoulin Island to the Garden Peninsula. We can find the so-called petrified honey-combs

and chains --- the remains of the walls of the homes of honey-comb and chain corals. These

coral fragments are known today as "Petosky Stones"...our state rock.

In the Silurian rocks we have the Niagara dolomite, the Salina salt

beds, and the Bass Island limestones. The Niagara stretches in broad outcrop from the

Garden Peninsula to Drummond Island. In the Northern Peninsula its underground beds are a

source of fresh water, gas and oil have been found in them in the Southern Peninsula. From

quarries in the Niagara, a calcium magnesian carbonate rock (dolomite), and a calcium

carbonate rock, limestone, are obtained.

Source: Photograph by Randy Schaetzl, Professor of Geography - Michigan

State University

The limestone is used as a source of lime (lime is created by burning/heating limestone

rock in kilns, thereby driving off the CO2) and is crushed for road metal,

concrete, and cement. It is used in the manufacture of calcium carbide and other

chemicals, in paper, sugar, and open hearth steel manufacture, and as a flux in iron and

steel blast furnaces. The dolomite is used for crushed stone, ballast, concrete, macadam,

in paper and in open hearth steel manufacturing. An important new use for Michigan’s

almost inexhaustible dolomites has been found--it is a potential source of metallic

magnesium so necessary in the manufacture of trucks, busses, airplanes, railway cars,

where strength and lightness are essential. The Niagara dolomites hold a potential reserve

of 400,000,000 tons of metallic magnesium. The problem of utilization, of course is one of

separation of the magnesium from the rock.

The thick sequence of Silurian (Niagara) dolomite that surrounds, and dips gently under, the Michigan Basin is very resistant to erosion. Therefore, it tends to form a prominent topographic feature (the Niagara cuesta) and it outcrops in many places as high, rocky cliffs. The eroded edge of these rocks forms an escarpment that can be traced almost continuously along the eastern part of Wisconsin, the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, and on east to New York State where Niagara Falls is formed by waters flowing off the Niagara dolomite onto the softer underlying shales. This escarpment is generally referred to as the Niagara Escarpment.

The extensive development of offshore carbonate rocks and an absence of sandstones and shales suggests that no landmass was present in the Great Lakes area.

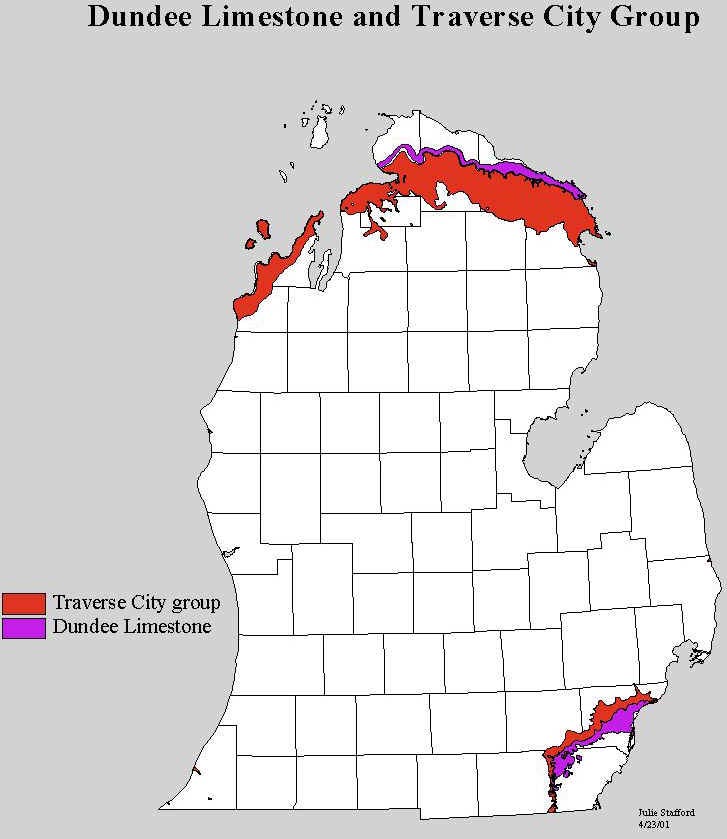

The Devonian was also a time of coral seas --- clear warm seas in which

millions of corals and moss animals lived and built great reefs and layers of lime mud

that became from 50 to 1000+ feet of limestone. Devonian outcrops in Wayne,

Charlevoix, Emmet, Cheboygan, Presque Isle, and Alpena Counties are quarried for limestone

and dolomite.

Source: Photograph by Randy Schaetzl, Professor of Geography - Michigan State University

The map below shows where some of the best limestone deposits of the state are located.

Hence, the large limestone quarries at Rogers City

and Alpena.

Source: Michigan State University, Department of Geography

These rocks are then used for flux in steel mills, as agricultural lime and in sugar refining. They are a large resource in the production of cement, crushed stone, in the chemical industries; in glass and paper manufacture; for water softener, gas purifier, and for construction purposes. The largest limestone quarry in the world is in the Rogers City and Dundee limestone near Rogers City, Presque Isle County. It is named the Calcite Quarry. For many year the "fines", or waste rock for which no use was known, were dumped into Lake Huron. Now they are being recovered and used in the chemical industries and for agriculture.

The Bayport limestone, the last (youngest) of the Mississippian rocks, is used for agricultural lime, in sugar manufacture, and for cement and concrete production. It is cut and used for building stone and in ornamental gardens. Many of our roadside parks in the southern part of the state have fireplaces and walls made of the Bayport limestone.

Parts of the text above have been paraphrased from C.M. Davis’ Readings in the Geography of Michigan (1964).

This material has been compiled for educational use only, and may not be reproduced without permission. One copy may be printed for personal use. Please contact Randall Schaetzl (soils@msu.edu) for more information or permissions.