MICHIGAN'S VEGETATION

Michigan was, for the most part, forested prior to European settlement.

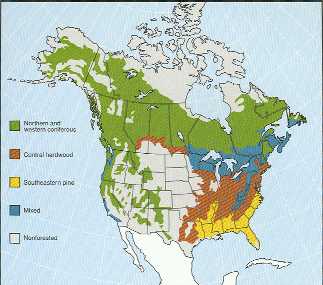

The map below shows major vegetation assemblages for North America, and illustrates

that Michigan's forests were primarily of the "mixed" type---that is, part

broadleaf trees and part conifers.

Click here for full size image (333 KB)

Source: Unknown

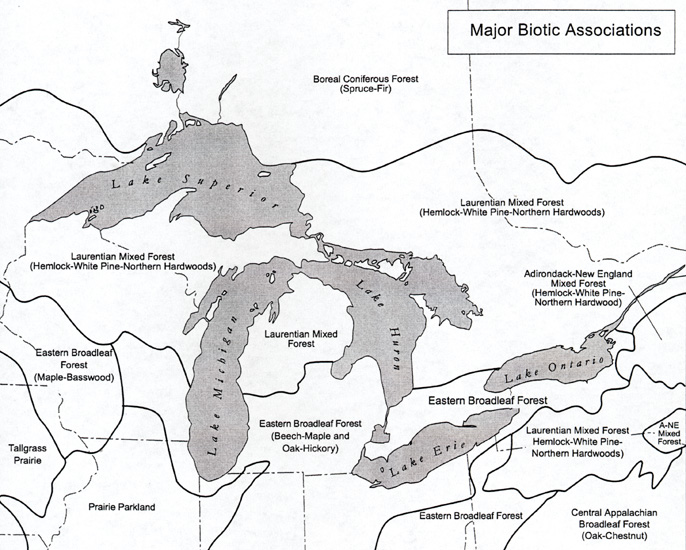

Actually, when examined on a finer scale, Michigan's forests can be divided into two major groupings: the deciduous forests (oaks, hickories, maples, beech) to the south, and mixed forests (pines, spruces, firs, beech, maples, oaks, aspen) to the north. The map below shows the general location of the boundary between these two forest provinces--called the floristic "tension zone".

Climate effects on forest patterns

Certain patterns in the present composition of forests in the Lower Peninsula

appear to be responses to climatic gradients that extend both south to north

and east to west across the state. Moving south to north through the Lower

Peninsula, one notices an increase in the number of evergreen (conifer) species.

These species (white spruce, balsam fir, jack pine) are boreal in distribution

but extend south into northern Michigan on upland sites where they are usually

only minor associates of other native hardwoods (though jack pine occurs

extensively on sandy uplands). Apparently sensitive to warm, dry summers

and neutral or basic soils, and unable to compete with more temperate-climate

associates, they are limited primarily to the northern Lower Peninsula--north

of a line from Bay City to Muskegon (the tension zone)--and to the Upper

Peninsula, where cooler summers and lower evaporation are typical, along

with the acidic, sandy soils on which these trees are most competitive. Warmer

summer weather with higher evaporation rates seem to restrict their occurrence

in southern Michigan.

Soil and topography effects on forest patterns

Probably no environmental factors account for more differences in forest

composition than do soil texture and topographic position. Both of these

factors strongly influence what amount of annual precipitation will actually

be available for plant growth on a given site and thus put limits on which

plants will be competitive there. Coarse, sandy soils are porous, have a

low water-holding capacity, are often acidic, and usually support trees such

as oaks and hickories--or in northern Michigan,

jack and red pine with a shrub layer of blueberries. Soils of intermediate

texture (loams) usually support a wide variety of species, but shade-tolerant

hardwoods such as beech and sugar maple

often dominate these sites. In the northern Lower Peninsula, hemlock and

yellow birch may prevail along with beech and maple, and in the western Upper

Peninsula, where there are no beeches, red oak and basswood are important

also. Heavy, clay-rich soils with poor internal drainage may support communities

of red or silver maple, ash, elm, and red oak.

The complex glacial history of the state left a jumbled

array of sediments that became soil, and since the

soil influenced the composition of both the primeval and present forests,

much of the patchwork of local forest patterns can be traced directly back

to the state’s glacial heritage. Topography influences forest composition

in that it is one of the factors that determines how far below-or above-ground

the water table will be. The woodlands that occupy low, boggy sites throughout

the state are among the most striking examples of this control. Bog vegetation generally exists where the water

table is at or slightly above the surface much of the year and where that

water is poor in minerals. Cold, poorly aerated soils discourage thorough

breakdown of organic matter, and therefore encourage the development of acidic

peat deposits. Such sites are heavily dominated by Canadian (boreal) elements throughout Michigan--spruce, fir,

larch, leatherleaf, blueberry--as these are the only plants that can be competitive

on acidic, cold sites.

The distribution of remnants of tall-grass prairie, found largely in southwestern

lower Michigan, is also partly related to topography. Vestiges of an earlier

prairie advanced into that part of the state from Illinois and Indiana during

a period of warmer, drier climate, and these prairies and oak openings persisted

on scattered patches of level or nearly level land of medium-or-better drainage

until European settlement. Presumable, the low relief of these sites exposed

them to a higher wind and fire risk. Once started by natural or human causes,

fires could sweep across the flat terrain more easily than they could on

the adjoining hillier landscape, resulting in damage to the invading woody

vegetation and preserving the isolated prairie stands long after their former

connection with the continuous prairie in Illinois and Indiana had been closed

off by reinvading forests.

For the map below, what forest types are represented by blue and

green? Yellow is tallgrass prairie, red is mid-grass prairie, and tan

is shortgrass prairie.

The image below is an interesting satellite composite of the percentage

of forest cover in the Great Lakes region. It shows nicely the large

amount of forested land in the UP, and the abrupt change from forest to grassland

in NW Minnesota.

Source: Unknown

The map below is a choropleth representation of forest cover.

Source: Unknown

Source: Image Courtesy of Randy Schaetzl, Professor of Geography - Michigan State University

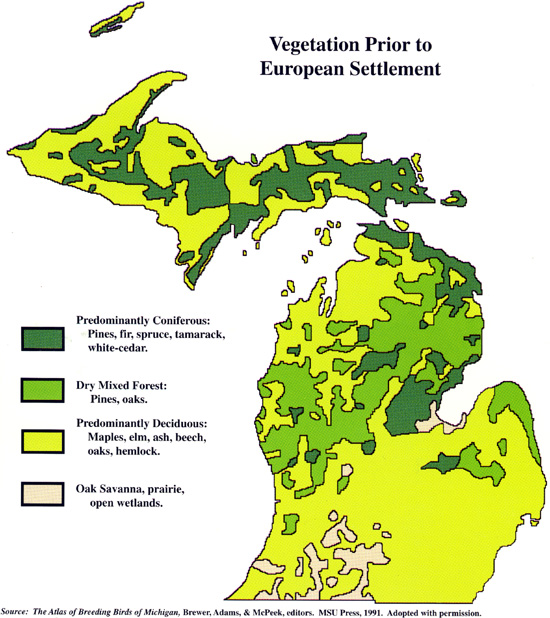

One way to evaluate the forest and vegetation resources of the state is to examine what they were like prior to European settlement. The series of maps below will give you an idea as to the patterns of vegetation in Michigan in the early 1800's. They start out more general, and become more detailed father down the page.

Source: Unknown

Michigan lies largely within the northern hardwood forest region, with areas

of the central hardwood region extending up into the southeastern part of

the state, and with pines, aspen and swamp conifers occupying large areas

in the northern part. Lines between these broad forest classifications are

frequently irregular, and within each are many different types, phases, and

temporary conditions, overlapping and changing with local variations of climate,

soil, and moisture.

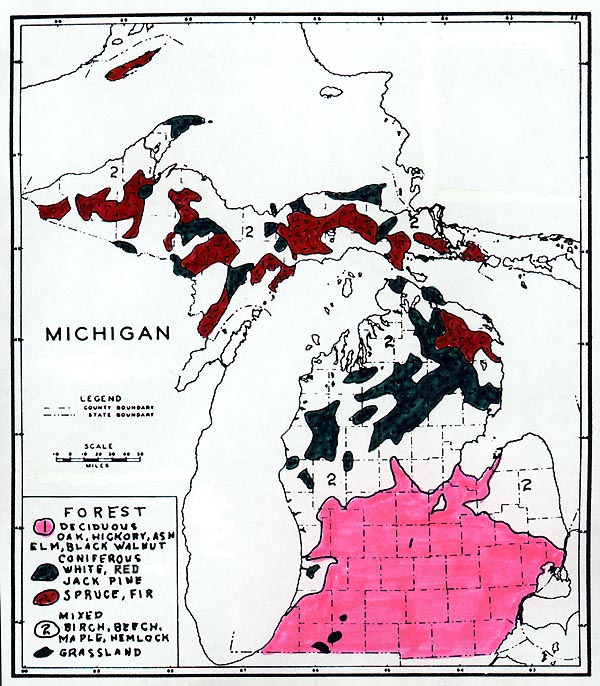

Presettlement forest types have generally been described

as primarily deciduous (hardwood) with oak, maple and beech in the southern

lower peninsula, changing to mixed deciduous/coniferous species groups including

maple, birch, hemlock, and pine further north. In reality, forest cover conditions

were much more complex. The southern lower peninsula was dominated by large

expanses of oaks where soils were drier, portions of savanna in the southwest,

and maples, elm, and ash in wetter soils near the Saginaw Valley. Settlement

removed the majority of mature hardwood forests throughout the south. Woodlots,

seldom larger than 100 acres adjacent to farmland, continue to be fractured

into smaller parcels near suburban areas.

The Upper Peninsula is dominated by northern hardwood

forests which occupy the better upland soils and which also occur in poorer

quality on lighter soils. These stands include principally sugar maple, elm,

basswood, and yellow birch, with beech present in the east half of the peninsula,

and with hemlock and white pine often in mixture. The large areas of sandy

plains found in many parts of the peninsula mostly support pines. Spruce,

balsam, cedar, and tamarack (larch), the swamp conifers, generally occupy

the poorly drained sites, while extensive areas of aspen occur throughout,

principally on burned-over lands.

In the Lower Peninsula northern hardwoods occupy the

extreme northern part, extending in a broad band along the northwest side

and into the central and southwestern sections. Yellow birch, hemlock, and

white pine occur with less frequency or are entirely absent in these stands

below the center of the state. Pine occurs principally in the broad sand

plains and hills region in the north central and northeast parts. Aspen covers

extensive areas of old burns throughout the north half of the Lower Peninsula,

while the swamp conifers occupy the poorly drained and wet sites.

The central hardwoods in general occupy the southeast

part of the Lower Peninsula and are characterized by the oaks and hickories

on the dry hilly soils, and by such species as sycamore, cottonwood, and

silver maple on the heavier soils and bottom lands.

Human intervention, such as harvesting, fire and clearing

for development, has profoundly affected the composition of Michigan’s forest

base. While the area of forest coverage has generally rebounded since the

timber boom period of the last century, few regions of the State contain

the same mixture of tree species that existed prior to settlement.

This "placemat" map was produced by the Michigan Geographic

Alliance and the Science/Mathematics/Technology Center, Central Michigan

University, with funding from the U.S. Dept. of Education. For further information

email Wayne.E.Kiefer@cmich.edu

Source: Atlas of Michigan, ed. Lawrence M. Sommers, 1977.

How do we know so much about presettlement vegetation patterns? Our

data come form the US Public Land Surveyors' records

and field notes. Recall that most of the United States west of the

original 13 Colonies was surveyed under the edicts of the Land Ordinance

of 1785 and Northwest Ordinance of 1787. These laws provided for the division

of unincorporated federal territory into six-by-six mile square townships

which were further subdivided into 36 sections each one square mile. In assaying

federal lands, contracted surveyors were also instructed to record things

like the condition of the land, its potential for agriculture, etc. Most

importantly for us, however, they also were required to note the species

and diameters of two or four trees at each section corner (i.e., 8-16 per

square mile), as well as major trees that fell on the section lines proper

(usually 5-15 per squate mile section). That’s a lot of trees! And that’s

a lot of paleo-vegetation information that we can use today to reconstruct

past forests! These General Land Office (GLO) archives--aside from their

valuable historical accounts and descriptions--have thus served as an important

data source for the reconstructing presettlement vegetation and ecology in

Michigan and elsewhere in the eastern United States.

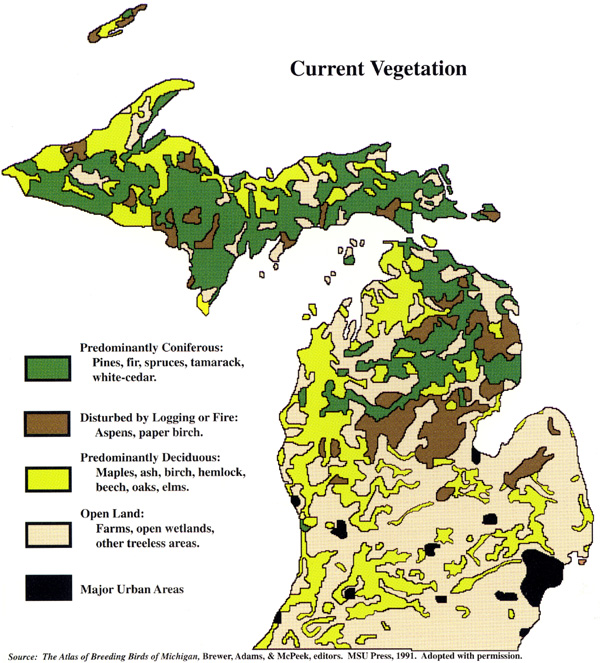

Michigan's current vegetation has been dramatically changed by its

inhabitants, as the map below shows.

This "placemat" map was produced by the Michigan Geographic Alliance and the Science/Mathematics/Technology Center, Central Michigan University, with funding from the U.S. Dept. of Education. For further information email Wayne.E.Kiefer@cmich.edu

LIST OF TREE SPECIES FOUND IN MICHIGAN

1. Oak-Savanna Community

Bur oak Quercus macrocarpa

Black oak Quercus velutina

Northern pin oak Quercus ellipsoidalis

2. Oak-Hickory Community

White oak Quercus alba

Black oak Quercus velutina

Red oak Quercus rubra

Pignut hickory Carya glabra

Shagbark hickory Carya ovata

Black cherry Prunus serotina

Hop-hornbeam Ostrya virginiana

White ash Fraxinus americana

Witch-hazel Hamamelis virginiana

Downy serviceberry Amelanchier arborea

Flowering dogwood Cornus florida

Eastern redcedar Iuniperus virginiana

Chinkapin oak Quercus muehlenbergii

Dwarf chinkapin oak Quercus prinoides

American chestnut Castanea dentata

Dwarf hackberry Celtis tenuifolia

3. Beech-Sugar Maple Community

Beech Fagus grandifolia

Sugar maple Acer saccharum

Red oak Quercus rubra

Basswood Tilia americana

White ash Fraxinus americana

Black walnut Juglans nigra

Tuliptree Liriodendron tulipifera

Bitternut hickory Carya cordiformis

Shagbark hickory Carya ovata

Slippery elm Ulmus rubra

Rock elm Ulmus thomasii

Alternate-leaf dogwood Cornus alternifolia

Blue ash Fraxinus quadrangulata

Downy serviceberry Amelanchier arborea

4. Deciduous Swamp Community

Red maple Acer rubrum

Black ash Fraxinus nigra

Yellow birch Betula alleghaniensis

American elm Ulmus americana

Silver maple Acer saccharinum

Blue-beech Carpinus caroliniana

Alternate-leaf dogwood Cornus alternifolia

Nannyberry Viburnum lentago

Pin oak Quercus palustris

Swamp white oak Quercus bicolor

5. Pine Community

Jack pine Pinus banksiana

Red pine Pinus resinosa

Eastern white pine Pinus strobus

White oak Quercus alba

Northern pin oak Quercus ellipsoidalis

Black oak Quercus velutina

Pin cherry Prunus pensylvanica

Scarlet oak Quercus coccinea

Parts of the text above have been paraphrased from

C.M. Davis’ Readings in the Geography of Michigan

(1964).

Parts of the text on this page have been modified from L.M.

Sommers' book entitled, "Michigan: A Geography".

This material has been compiled for educational use only, and may not be reproduced without permission. One copy may be printed for personal use. Please contact Randall Schaetzl (soils@msu.edu) for more information or permissions.