NORTHERN HARDWOODS

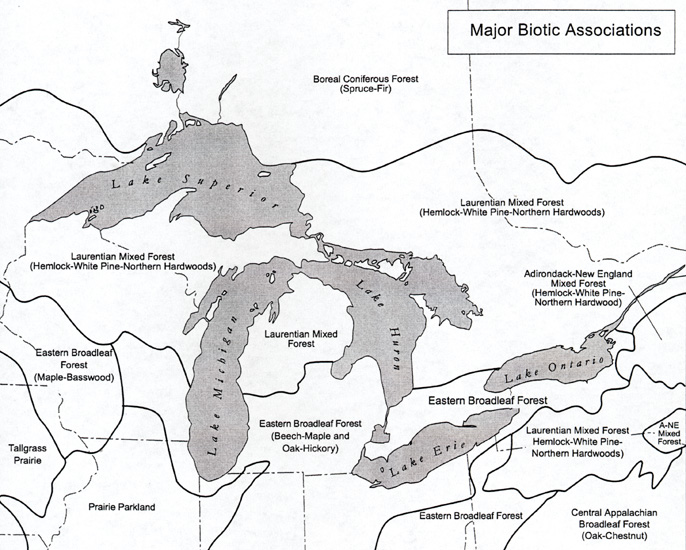

"Northern hardwoods" is a general term that refers to an association of

broadleaf trees that occur in various combinations throughout the eastern and northern

United States. Typical tree species include sugar maple, basswood, beech, hemlock

(a conifer), yellow birch, American elm, ironwood, white pine (a conifer), and red maple.

Coarse, sandy soils are porous, have a low water-holding capacity, and

are often acidic. These types of soils usually support trees such as oaks and hickories--or in northern Michigan, jack and red pine with a shrub

layer of blueberries. Soils of intermediate texture (loams), however, usually

support a wide variety of species, but shade-tolerant "northern hardwoods" such

as beech and sugar maple (below) often dominate these sites. The term

"shade-tolerant" implies that the trees are able to reproduce (i.e., their

seedlings can survive) in the shade of the parent plants. Many northern hardwood

stands are quite dark, as the two images below illustrate.

Source: Photograph courtesy of Randy Schaetzl, Professor of Geography -

Michigan State University

Source: Photograph courtesy of Randy Schaetzl, Professor of Geography -

Michigan State University

What is Shade Tolerance? It is the capacity of a tree species to survive in

light of low intensity, or the relative capacity of a species to grow under low light

conditions and high root competition (in the understory environment).

In the northern Lower Peninsula, hemlock and yellow birch may prevail along with beech and

maple, and in the western Upper Peninsula, where there are no beeches, red oak and

basswood are important also. Forest assemblages composed of maple, beech, hemlock,

birch, and other broadleaf tree species are referred to as "northern hardwoods"

("Laurentian mixed forest" on the map below).

Source: Image courtesy of Randy Schaetzl, Professor of Geography - Michigan

State University

A less conspicuous forest gradient exists from the central to the western portions of the

Lower Peninsula. Woodland composition in the central Lower Peninsula is a mosaic of

beech-maple mixed with some oak-hickory communities (on sandier soils). Westward through

the state, however, the more drought-sensitive beech-sugar maple forests become more

common, and north of about Muskegon, they are mixed increasingly with yellow birch and

hemlock. Close to Lake Michigan, these communities may be found even on sandy soils that

in the interior could support only dry, oak-hickory-pine

forests. This westward increase of beech, sugar maple, and other drought-sensitive

associates may be related to climatic modifications by Lake Michigan. Augmented winter

snowfall (lake-effect) and, on the sand dune sites

near the water itself, lower summer temperatures may combine to create a more generous

amount of water and thus permit these species to compete near the lake on coarser soils

than they could flourish on in the interior. This pattern is particularly evident near the

shoreline in the central and northern Lower Peninsula, where dune soils consisting of more

than 90% sand may support a mixture of mesic (moderately moist) forest species along with

boreal elements (jack pine, balsam fir, white spruce).

Source:

Photograph courtesy of Randy Schaetzl, Professor of Geography - Michigan State

University

Beech (leaves shown below) and sugar maple (ditto) are present on the moister upland

forest sites (which usually have heavier soils) north of the tension

zone, but are associated in this region with hemlock and yellow birch, as well as with

some of the associates that are characteristic farther south. Locally, balsam fir and

white spruce are minor constituents. These communities, too, may have been heavily

disturbed by lumbering, leading to dominance by aspen, red maple, white birch, and sugar

maple depending on site factors.

BEECH

MAPLE

Source:

Photograph courtesy of Randy Schaetzl, Professor of Geography - Michigan State

University

Source: Photograph courtesy of Randy Schaetzl, Professor of Geography - Michigan State University

Source: Photograph courtesy of Randy Schaetzl, Professor of Geography - Michigan State University

Spruce trees are recognizable by their short needles, which have rounded ends, and by

their cones, which hang downward. Spruce makes up a small part of the mixed forest

associations of northern Michigan, usually on wetter or colder sites.

Much of the topography in the western Upper Peninsula is controlled by bedrock; that is, the hills and valleys consist of rock rather than of loose glacial debris like most of the remainder of the state. The associated upland forests are similar to the beech-maple stands discussed earlier except that beech is absent and its place in the canopy is taken by other associates, especially yellow birch. Scattered white and red pines are more common. Excellent examples of this type of forest can be seen in the Porcupine Mountains and Tahquamenon Falls State Parks. Heavy logging of these forests has led to extensive mixed stands of maple, white birch, quaking aspen, and balsam fir. Similar upland forests, with the addition of beech, are found in the eastern Upper Peninsula. Taken as a unit, however, this region differs from the western Upper Peninsula in that the wetlands cover a far greater proportion of the landscape.

Source: Photograph courtesy of Randy Schaetzl, Professor of Geography -

Michigan State University

Source: Photograph courtesy of Randy Schaetzl, Professor of Geography - Michigan State University

Parts of the text on this page have been modified from L.M. Sommers' book entitled, "Michigan: A Geography".

This material has been compiled for educational use only, and may not be reproduced without permission. One copy may be printed for personal use. Please contact Randall Schaetzl (soils@msu.edu) for more information or permissions.