Prairies are a type of grassland, a landscape dominated by

herbaceous plants, especially grasses; trees are either absent or only widely scattered on

the landscape. Grasslands occur in many regions, such as the llanos of Venezuela,

the pampas of Argentina, the cerrado and campos of Brazil, the steppes of central Asia,

and the grasslands of Australia. Approximately 32 to 40% of the world's land surface

is, or was, covered by grasslands. Today, grasslands are extremely important for

agriculture, and approximately 70% of the food produced for humans comes from these

regions.

Source: Photograph courtesy of Randy Schaetzl, Professor of Geography -

Michigan State University

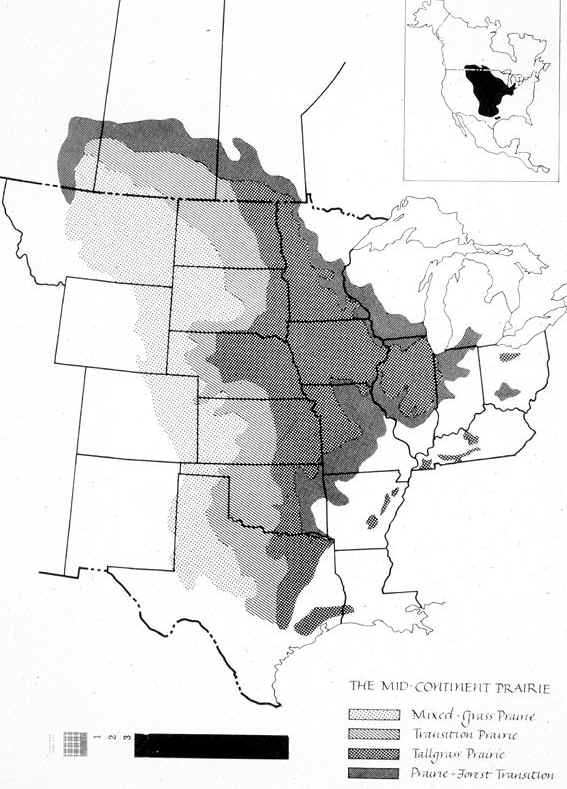

Grasslands are the largest vegetation type in North America, covering approximately 15% of

the land area. Prairies are the grasslands found in the central part of the North

American continent. They form a more or less continuous, roughly triangular area

that extends for about 2,400 miles (3,870 km) from Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba

southward through the Great Plains to southern Texas and adjacent Mexico and approximately

1,000 miles (1,612 km) from western Indiana westward to the foothills of the Rocky

Mountains, covering 1.4 million square miles. Rainfall decreases from east to west,

resulting in different types of prairies, with the tallgrass prairie in the wetter eastern

region, mixed-grass prairie in the central Great Plains, and shortgrass prairie towards

the rain shadow of the Rockies. Today, these three prairie types largely correspond

to the corn/soybean area, the wheat belt, and the western rangelands, respectively.

Source: Photograph courtesy of Randy Schaetzl, Professor of Geography -

Michigan State University

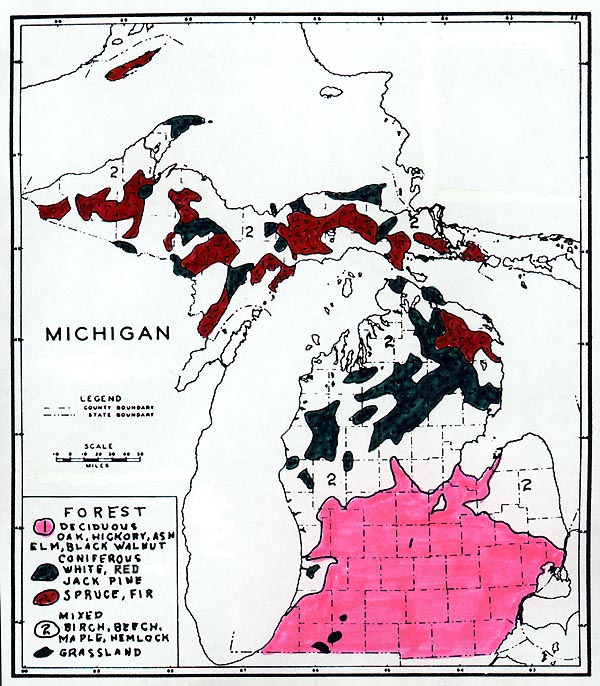

Michigan lies on the far eastern edge of an area called the

"prairie peninsula," an eastward extension of prairies that borders deciduous

forests to the north, east, and south. This is part of the tallgrass prairie region,

sometimes called the true prairie, with the landscape dominated by grasses such as big

bluestem and Indian grass as well as a large number of other species of grasses and

wildflowers, the latter called forbs. The tallgrass prairie vegetation sometimes

reaches a height of 10 feet or more.

Source: Unknown

How did prairies form?

As the climate became warmer and drier, between 14,000 and 10,000 years ago, a cool mesic

hardwood forest with ash, oak, elm, maple, birch, and hickory trees grew in the midwest.

About 8,300 years ago, the climate became substantially warmer and drier, and within the

relatively short time of 500 to 800 years, most of the forests in southwestern Michigan

died out or got burned down, except along stream banks, and prairies spread over the

landscape. During the last 1,000 years the climate has become slightly cooler and

wetter, making conditions more favorable to trees. Savannas,

characterized by a grassy prairie-type ground cover underneath an open tree canopy, are

common in areas that border the prairies. Scattered out on the prairie were patches

of rich forests completely surrounded by prairie; these forests are called prairie groves.

Prairies developed and were maintained under the influence of three

major non-biological stresses: climate, grazing, and fire. Occurring in the central part

of North America, prairies are subject to extreme ranges of temperatures, with hot summers

and cold winters. There are also great fluctuations of temperatures within growing

seasons.

Source: Unknown

During periods of drought, trees died and prairie plants took over previously forested

regions. When rainfall was abundant and fires few, the trees and forest were able to

reestablish themselves. Prairie fires, started either by lightning or by Native

Americans, were commonplace before European settlement. Any given parcel of land probably

burned once every one to five years. These prairie fires moved rapidly across the prairie,

and damaging heat from the fire did not penetrate the soil to any great extent. Fire kills

most saplings of woody species, removes thatch that aids nutrient cycling, and promotes

early flowering spring species. Today fire also is beneficial to control non-native

herbaceous species that can invade prairie remnants.

A considerable portion of the above ground biomass of a prairie was

consumed each year by the grazing of a wide range of browsing animals, such as bison, elk,

deer, rabbits, and grasshoppers. This grazing was an integral part of the prairie

ecosystem, and therefore grasslands and ungulate mammals coevolved together. Grazing

increased growth in prairies, recycles nitrogen through urine and feces, and the trampling

opens up habitat for plant species that prefer some disturbance of the soil. Prairie

plants have adapted to these stresses by largely being herbaceous perennials with

underground storage/perennating structures, growing points slightly below ground level,

and extensive, deep root systems. The tender growing points of prairie plants occur

an inch or so below ground and are usually not injured by prairie fires, which move

rapidly across the prairie. These underground growing points are also left unharmed

by browsing animals. During droughts, the deep roots of prairie plants are able to

take up moisture from deep in the soil.

Prairie remnants exist today in areas that have been

repeatedly burned, because fire assists the grasses and eliminates woody plants that might

otherwise overtop the grasses and shade them out. The best places to find prairie remnants

are along old RR rights of way, which occasionally were burned as sparks and cinders were

thrown out of passing trains. Prairie remnants are also observable in old cemeteries built

originally on patches of prairie. The last prairie remnant in Monroe County, the

Minong Prairie, is found just 13 miles north of the Ohio/Michigan state line within the

Petersburg State Game Area.

Prairies in Kalamazoo County

Source: Peters,

B.C. 1970. Pioneer evaluation of the Kalamazoo County landscape. Michigan

Academician 3(2): 15-25.

Today, most of Michigan's prairies have been converted to agriculture, as this image

below, from Iowa, shows (with prairie in the foreground and corn in the background).

Source: Photograph courtesy of Randy Schaetzl, Professor of Geography -

Michigan State University

Still, some areas of prairie exist in Michigan, such as this one in Middleville, in SW

Michigan. This particular prairie is located within a cemetary, and for that reason

it has not been plowed or otherwise destroyed. Like many prairies, it requires

occasional fires to keep woody vegetation at bay. The Nature Conservancy bought the

cemetery and occasionally does burn it, preserving the tallgrass character of the place.

Source: Photograph courtesy of Randy Schaetzl, Professor of Geography -

Michigan State University

Source: Photograph courtesy of Randy Schaetzl, Professor of Geography -

Michigan State University

The first European settlers moving westward from the forests of the eastern United

States encountered the prairies, which seemed like a vast ocean of grass. The wind caused

waves on the surface of the shimmering grasses. One type of wagon used by the

pioneers was the "prairie schooner," a reference to a sailing vessel, further

adding to the analogy of the prairie being a large inland sea of grasses. It was

easy to get lost in the prairie, especially since there were few trees or other natural

features to act as landmarks. Even when on horseback, it was often not possible to

see across the prairie to the horizon. Today, many of these landscapes are in irrigated

corn. A few oaks remain as a testament to the presettlement forest vegetation that

surrounded the prairies (the oak openings).

Source: Photograph courtesy of Randy Schaetzl, Professor of Geography -

Michigan State University

Click here for some links to web sites devoted to prairies.

This material has been compiled for educational use only, and may not be reproduced without permission. One copy may be printed for personal use. Please contact Randall Schaetzl (soils@msu.edu) for more information or permissions.