The French colonists of the St. Lawrence River valley were the first Europeans to move into the western Great Lakes, or pays d’en haut ("upper country"). Samuel de Champlain had been the first European to become curious about Michigan’s "water wonderland." On his first visit to the St. Lawrence River in 1603, he heard from the Indians about an all-water route far into the wilderness. They described the copper mines near a vast freshwater lake, which they revered and which the French were to call "Lac Sup�rieur." Probably the hardy mariner raised a doubtful eyebrow, but he was a born explorer and decided to investigate. He sent out reconnoitering parties, made several trips in person, and by 1615 had seen Georgian Bay in Lake Huron. Before his death in 1635, Champlain laid the foundations of French empire in North America and gathered a treasure of information about the western wilderness, including Michigan. A report of his explorations, printed at Paris in 1632, contains a map that crudely delineates most of the Great Lakes, the lower peninsula of Michigan, the Detroit River, and the falls ("Sault") on the strait between lakes Huron and Superior. This is the first map showing the Detroit River.

Besides expanding the fur trade, the French wanted to find a river passage across North America (for a trade route to Asia), explore and secure territory, and establish Christian missions to convert Native peoples. The government of Nouvelle-France (New France) in Montreal received permission from the Huron Indians to let young Frenchmen live among them, adopt their language and customs, and become familiar with the landscape and water routes. Champlain had the ability to inspire young men with his own eagerness to study the geography and Indian life of the western forests.

And so �tienne Brul�, a fur trader and interpreter, for more than 20 years lived in smoky lodges, ate greasy food, puffed the pipe, swapped stories, and learned the tribal languages and ways.

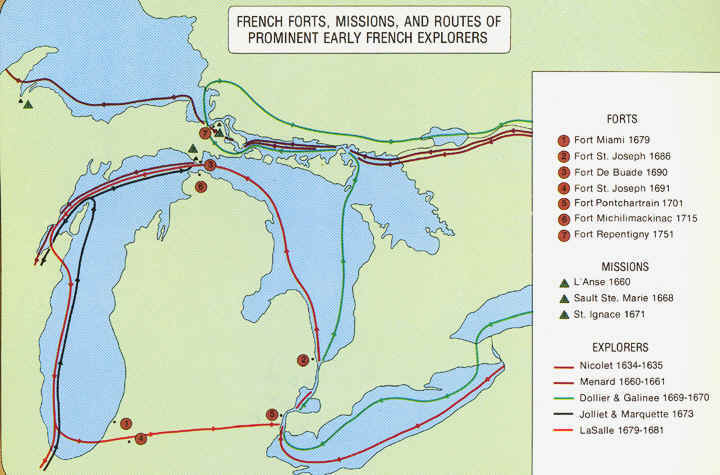

He roamed all over the Great Lakes country, and probably was the first European to see northern Michigan. Br�l� may have explored as far west as Lake Superior in 1621-23. In the 1600s the French explored along water routes (such as the Fox and Wisconsin rivers) connecting the Great Lakes with the Mississippi River. They built forts, missions, and trading posts along the strategic routes, long used by native peoples for trade.

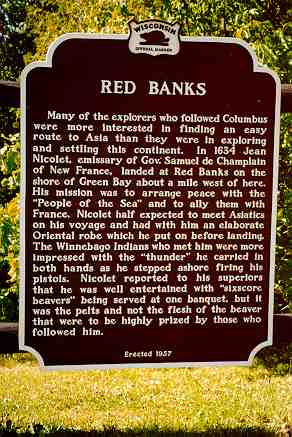

Another of Champlain’s fearless disciples was Jean Nicolet (below), who spent many years living like an Indian and became a commissary and interpreter for the company that controlled Canada. de Champlain, French governor of Canada, had heard from natives of a "people of the sea" who dwelt in the "land of the stinking water." Believing that the "stinking water" might be salt water, he was eager to explore new routes to the west. A few years later in 1634 Jean Nicolet passed through the Straits of Mackinac on his way to "the land of the stinking water" which he assumed to be the Pacific Ocean. What he found; however, were only a few Indian tribes that camped along the shore of the westernmost Lake Michigan (below).

Source: Photograph by Randy Schaetzl, Professor of Geography - Michigan

State University

But the trail was blazed and in the 17th century the French government sent settlers to

the new world who traded with the Indians for their beaver pelts and Catholic Jesuit

missionaries who sought to save their souls.

Champlain pointed to Nicolet when the government wanted a shrewd and

hardy diplomat to plunge into the unknown and make peace with the Winnebagoes of Lake

Michigan. In 1634 Nicolet threaded the Straits of Mackinac and skirted the northern shore

of Lake Michigan to Green Bay. The myth of a short and easy passage through America to

Asia was still believed, and his baggage contained an impressive silk robe to wear when he

should be introduced to an Oriental potentate. He won renown as the first European to pass

the Straits, travel on Lake Michigan, and visit Wisconsin.

Traders and trappers came and went, but the impulse for permanent

settlement came from the church. The Jesuit Fathers Dablon and Marquette planted the first

lasting communities in Michigan, at Sault Ste. Marie in 1668 and at St. Ignace 3 years

later. These missions were inspired by Father Claude Allouez, who preached in the St.

Joseph Valley and reported on the Upper Peninsula copper mines.

Father Dablon in 1670 accompanied Allouez to Green Bay to investigate

rumors about a vast western river that flowed southward to the sea. That journey started

an exciting chapter in Michigan’s history, for it led Dablon to appoint Father

Jacques Marquette to go with Louis Jolliet on his famous expedition to locate the

"Father of Waters." These French explorers were the first to hear about an area

the Indians called "Mississippi," which meant "Great Water."

Father Pere Jacques Marquette first saw Michigan when he arrived at the

Sault mission in 1668 and skirted the coast of the Upper Peninsula. In 1673 Louis Joliet,

a cartographer and merchant who had already discovered Lake Erie, was accompanied by the

Jesuit missionary, Pere Jacques Marquette, and five canoe paddlers. The men in this

expedition started from St. Ignace to find the Mississippi, and were the first Europeans

to see the region where the city of Peoria, Illinois now stands. By revealing the rich

vastness of the upper valley, their trip inspired the dream of a French inland empire,

which eventually rose with its chief stronghold and capital at Detroit.

The hardships of that great adventure undermined Marquette’s

health, and he died in 1675 on the site of Ludington, while attempting to return to St.

Ignace along the eastern shore of Lake Michigan. They buried him near the mouth of the

river now named for him (the Pere Marquette).

The world began to appreciate Marquette’s greatness 6 years after

his death, when Thevenot published a collection of travels containing the first printed

account of Marquette’s journey to the Mississippi, based upon his diary. The map

accompanying it does not show Michigan, but is thought to be the first one bearing the

State’s name, indicating "Lac de Michigami o� Illinois."

Source: Atlas of Michigan, ed. Lawrence M. Sommers, 1977.

Marquette (shown below) was born in Laon, France. In 1666 he learned

Indian Languages in Quebec, Canada. Marquette preached among the Illinois Indians until

his death in 1675.

French colonial ambitions soon projected a center of power on the

strategic strait between Lakes Erie and Huron. Antoine de la Mothe Cadillac, an

energetic and ambitious young man in Canada dreamed of an oasis of French culture in the

wilderness. He was a favorite of the wily Count Frontenac, Governor of the French

possessions in North America. In 1694 Frontenac sent Cadillac to command Fort

Michilimackinac (I know... that’s a lot of "..’ac’s in one sentence)

at the current site of Mackinac City. Fort Michilimackinac must have looked something like

this.

There he spent three years, and upon returning to France in 1699, established a stronghold

at "Le D�troit." In June 1701 Cadillac left Lachine near Montreal accompanied

by soldiers and workmen with provisions and tools. On July 24, they landed at the site of

Detroit and began to clear away the woods and erect a stockade and buildings for

"Fort Pontchartrain du D�troit." In so doing, Cadillac founded the modern-day

city of Detroit.

Cadillac shrewdly selected a site ideal for the control of the Indians

and the waterways, and for over 50 years Detroit was the center of French power in the

Northwest and the cultural capital of inland America. Cadillac dominated it for a decade,

planting it so firmly that his enemies could not uproot it.

Half a century later "Le D�troit" was still most of

Michigan, and it still seemed very rustic. The outlying farms, "Settled in a String

Along the Water Side," and estimated the whole population at about 360 families.

The country folk or habitants of early Detroit (Fort

Pontchartrain) generally dwelt in low whitewashed houses. Enclosed in front by heavy

picket fences, they faced the primitive road that ran for miles along the river bank.

Behind them stretched out-buildings and barnyards, orchards, and cultivated fields, ending

in the dusk of the primeval forest. The farms were narrow strips, sometimes several miles

long and with only a few hundred feet of river front. This sort of layout was called

"long lots". Such was the small and rustic

colony by which France expected to hold a continent against the growing imperial might of

Great Britain.

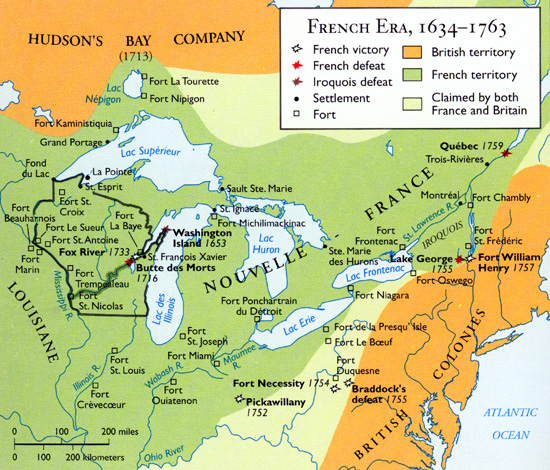

In 1686 Fort St. Joseph rose at the present site of Port Huron to

protect the fur trade from the English. In the 1710s, the French built new forts

along the Great Lakes and the Fox, Wisconsin, and Mississippi rivers. British encroachment

on the fur trade helped lead to the French and Indian War and the French loss of the

region to Britain in 1763.

After over a century of exploration and half-hearted efforts to

colonize, nearly all of Michigan was still a virgin wilderness. In 1765 a survey of the

region revealed an abundance of livestock and large crops of wheat and corn. But there

were only about 800 people in Detroit and the nearby farms, and less than 100 in the Fort

Pontchartrain.

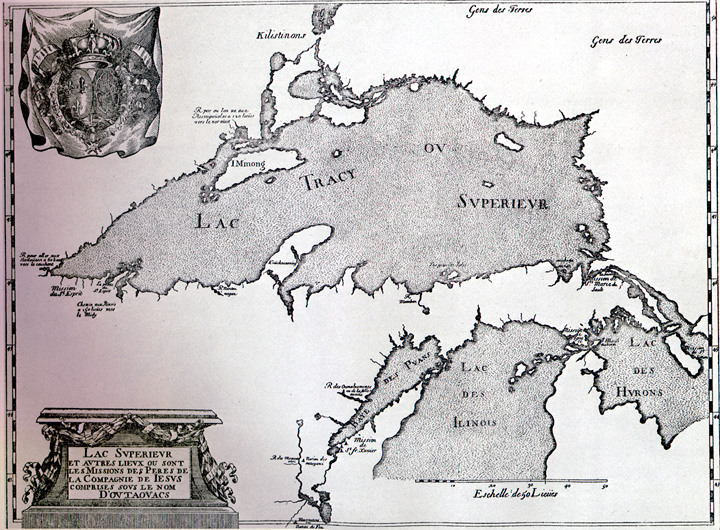

Early French explorers were not only looking for furs and interested in converting the

Indians to Christianity, they were also trying to find a passage to the Pacific.

Thus, they were conscientious about mapping the inland waterways, since one of them might

provide a route to the riches of the Orient. Maps such as the one below were some of

the best navigation "tools" early explorers had, and we have the French to thank

for that.

Source: Public Domain

The map below shows what lands the French controlled in the period 1634-1763. The French and Indian war was fought between the French and

the British to determine who would control these lands and their valuable fur trade.

It ended after the British defeated the French in Quebec. Britain and France signed

a treaty ending the war in Paris in 1763. The British had won the French and Indian War.

Source: Atlas of Wisconsin

The French explorers in the 17th century found the land virtually untouched. French farming was limited in scale, because from the beginning, the crown’s New World interests centered more on the lucrative lumber and fur trades than on agriculture. One notable exception was in the cultivation of fruit trees, especially pear and apple, and the French developed three new apple varieties in and around Detroit.

Some of the text and images in this page have been modified from C.M. Davis’ "Readings in the Geography of Michigan" (Ann Arbor Publishers).

This material has been compiled for educational use only, and may not be reproduced without permission. One copy may be printed for personal use. Please contact Randall Schaetzl (soils@msu.edu) for more information or permissions.