Long Lots: How they came to be

The early French government tried to transplant a vestigial form of feudalism, the

seigneurial system, to its possessions in Canada. It granted large acreages of land to

seigneurs, who were expected to bring in tenants to settle and work the land. In return,

the seigneur had certain feudal rights over his tenants: to receive token rent payments

from them, to require them to use his mill for grinding their grain, to demand various

work services from them. The feudal elements of this system quickly became irrelevant in

the New World, where land was available in abundance for tenants who felt oppressed and

wanted to move, but the long-lot system of land division associated with seigneuries

remains vividly imprinted on the landscape of North America that were settled by

French-speaking people. Long lots can be found in many parts of Canada, where the French

influence is strong, and near Detroit (for the same reason).

The French settlers were more interested in the fur trade than they

were in farming, and the seigneuries were laid out to give maximum access to the rivers

that were the main routes to the interior. Each seigneury (or, long lot) had a fairly

narrow frontage on the river, but extended far back from it. Each was subdivided into long

narrow strips that were only 350 to 600 feet wide but ten times as deep. At the back end

of the strips a road ran parallel to the general course of the river, and this road

provided the frontage for a second range of strips when the first range was fully

occupied.

Source: Unknown

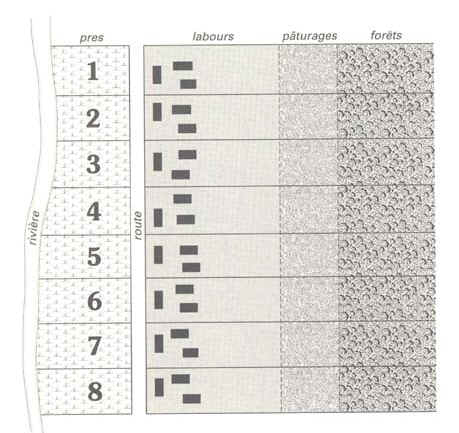

The long-lot system of land survey (below) was cheap and easy, and it

gave each farm equal amounts of each kind of soil on the floodplain, the terraces, and the

interfluves. It gave access to a transportation artery (river or road) for a maximum

number of farms. Each family could live on its own farm but still be close to neighbors.

Each family developed its farm progressively, but clearing the forests near the farmstead

first and leaving the more remote parts until later. Some farmers built isolated barns at

the far ends of their farms to reduce the labor of hauling crops in to the farmstead and

manure back out to the fields.

Source: Unknown

The long-lot system of land survey has some disadvantages. Few rivers

follow straight lines; the twists and turns of a meandering river complicated the survey,

the "long lots" inside narrow bends were likely to be bobtailed, and

considerable litigation was virtually inevitable if the river changed its course. One of

the most serious drawbacks of the long-lot survey system was related to inheritance. Farms

were split right down the middle when the owner died, and farms that were already narrow

became far too narrow when they were divided equally among the children, especially when

families were as large as they often are in French Canada. The image below is of an

island in the St. Lawrence River; it is obvious from the photo that the island's land

holdings were carved up using the long lot system.

Source: Unknown

Despite these drawbacks, the French carried the long-lot survey system

with them wherever they settled in North America. They remained more interested in fur

trading than in farming, and except in Louisiana the settlements that developed beside

their trading posts were small and grew slowly. The principal mark they have left on the

land is the remnants of their land-division system, which are still visible on modern

topographic maps of Detroit, of Green Bay, and of Vincennes, Indiana, as well in

Louisiana.

Source: Unknown

This material has been compiled for educational use only, and may not be reproduced without permission. One copy may be printed for personal use. Please contact Randall Schaetzl (soils@msu.edu) for more information or permissions.