Logging and milling had begun in earnest between 1830 and 1840. In general, the pine lands and the central, southern, and eastern areas were logged first and most completely, and were then subject to damaging fires which followed. These were the drier sites which had most pine to begin with, and were so situated and continuous as to be in the paths of many fires which raced from west to east with the prevailing winds. These were also the areas in which ill-advised agricultural efforts, encouraged by land speculators, stimulated land clearing by early settlers. Patches of timber of varying size, protected on the west by either open water or wet swamps, or to a lesser extent, hardwood sites, escaped some of the fires which swept around them, but sooner or later many of these burned too.

Northern hardwood (maple, beech, basswood) forests seem to have suffered less from the combination of drastic cutting and fires. Swamp conifer stands, in wet sites, were least subject to loss from fire. Settlers were not tempted to clear these wet lands for farming. Once the old white pines were cut from the swamps, in many places natural regeneration and growth followed, resulting in the continuation of the forest conditions.

Source: Unknown

Forest fires in many extensive areas not only killed the trees and

consumed the thin mantle of topsoil and eliminated every possible source of seed or

sprouts to bring back the previous forest. In some areas, notably parts of Kalkaska,

Missaukee, Crawford, Osceola, Wexford, Luce and Clare counties, even today areas of

fire-charred pine stumps on otherwise almost barren sand plains are to be found. The Kingston Plains is an excellent example of this type of

landscape. Early farming efforts, many of which failed, were responsible for completely

denuding land, which was then (of course!) later abandoned.

The logging "heyday" fizzled out by World War I...much

earlier in the lower peninsula, however. The early 1920's was the beginning of the end of

the great forest fires, and the start of effective fire control, made possible with an

increased network of roads, the presence and determination of men to do the work, and

intermittent expanses of treeless–even brushless–land to break the fires. The

"passing of the pine," which was followed immediately by fires, was then

followed by rapid harvest of the hardwoods (broadleaf trees) that still stood. Hardwoods,

such as maple, basswood, beech and oak, were generally smaller trees that required more

effort to harvest. Thus, most logging activities in Michigan slowed to a snail’s

pace.

The furniture plants of Grand Rapids and other cities, as well as

flooring plants in many locations, were ready markets for hardwood lumber. Thus, timber

production here never really hit rock bottom. At its lowest point, there were a few

remnants and patches of second growth timber which kept small sawmills running and

supported the slow growth of a new industry: paper.

Paper mills, using pulpwood as raw material (small logs, not large

enough to saw for lumber), had become established at several locations prior to 1900.

These quite small mills consumed spruce almost exclusively at first, later adding balsam

fir, hemlock and jack pine, and using trees of species, sizes, and quality not acceptable

for lumber production.

Relatively free from both fires and a hungry logging industry, the

quiet forests dropped seeds, sent up sprouts, and grew as vigorously as the land, the

climate, and the then ragged tree populations would allow. Thus, the comparative lull in

industrial activity and production of timber products allowed for a period of rapid

regrowth of Michigan’s forests. From 1935 to 1955, timber volumes in this area

doubled, and this "thickening up" of forests improved their economic

attractiveness to industries. It also added immeasurably to the scenic and recreational

quality of the area, attracting increasing numbers of summer visitors and hunters in the

fall.

The 20th century brought new life to Michigan’s lumber industry. Reforestation

began in the 1920s, initiating the slow process of rejuvenation. Trees planted in 1920

were sawtimber size in 1966, and Michigan once again took the lead in timber production in

the Great Lakes area. Today, the forest industry is partially recovered, but its focus has

changed considerably as the center of the state’s economy has shifted elsewhere.

Michigan is currently a leading world supplier of bird’s-eye maple and Christmas

trees. The Grand Rapids furniture industry, begun in

1836, survived by importing hardwoods when native species grew more scarce, and the city

is still a major furniture center. But of the once vast expanse of white pine, only a few trees remain those serve as

reminders of the boom years a century past.

Look around. The majority of the forest growth which became established

and has dominated this region since the early logging era originated in a relatively short

span of years--mostly between 1910 and 1935, after the last of the big fires. The youngest

of the present stands originated in one of three ways: (1) natural regeneration that

followed more recent timber harvesting of the second-growth and remnant stands, (2)

continuing spread of seedlings and sprouts from adjacent stands into treeless areas, (3)

artificial regeneration (planting) of trees by humans.

Long before the end of either the Paul Bunyan era of logging or the big

forest fires, farsighted men were at work planting tress to reforest the barren lands. The

first state forest nursery was established at Higgins Lake in 1904, and from that early

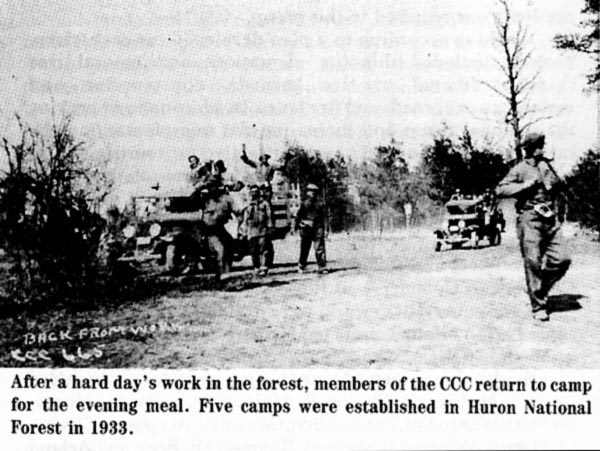

start, tree planting aided greatly in rebuilding the forest resources. The Civilian

Conservation Corps (CCC) of the Depression era boosted the reforestation movement by

supplying manpower for the job. Red, white, and jack pine, and other conifers were planted

on good sites and poor, and are now very evident in the State. Much of the planting of

private lands shortly after World War II was of Scotch pine intended for harvest as

Christmas trees. However, many of these plantations have been allowed to grow untended,

and are now beyond such possible use. The total area successfully planted is estimated at

over 250,000 ha as of the 1960's. It is quite evenly distributed between private lands,

state, and national forests.

Source: Image courtesy Michigan History Magazine

Important date: MAY 2, 1933. Two hundred young men from Detroit arrive at an

isolated spot in Chippewa County and set up Camp Raco--Michigan's first Civilian

Conservation Corps (CCC) facility. Within months, dozens of similar camps open across

northern Michigan. One of President Franklin D. Roosevelt's most popular New Deal relief

programs, the CCC is a massive conservation program that employs tens of thousands of

young men all across the nation. The CCC revitalizes Michigan's state park system,

establishes Isle Royale National Park and builds campgrounds in Michigan's national

forests. All will benefit the state as tourism becomes one of its main economic resources.

Michigan enrollees also send home $20 million of their monthly salaries and acquire

invaluable training that will make their transition to military service in World War II

easier. When the program ends in 1942, over 100,000 Michigan men will have served in the

CCC. Their accomplishments will include: planting over 484 million seedlings (more than

twice the number in any other state), expending 140,000 man-days in fighting forest fires,

placing 150 million fish in rivers and lakes, and constructing 7,000 miles of truck

trails, 504 buildings and 222 bridges.

Source: Image courtesy Michigan History Magazine

This material has been compiled for educational use only, and may not be reproduced without permission. One copy may be printed for personal use. Please contact Randall Schaetzl (soils@msu.edu) for more information or permissions.