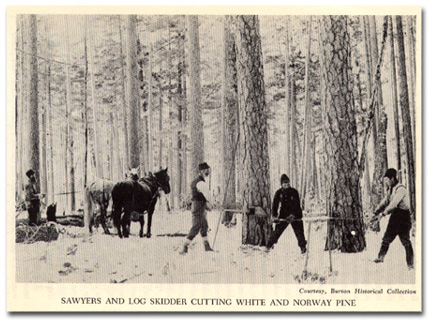

Let's discuss white pine logging in logical fashion. First, how were the trees cut?

Answer: by hand, with cross-cut saws or axes.

Source: Unknown

After the timber cruisers found the best stands of pine, the crew would come in and build

a camp, which consisted of a bunkhouse, cook shanty which had a dining room and kitchen,

the most important part of camp. There was a blacksmith and a carpenter as well as a

granary and barn for the animals. The camp store would have the basic supplies need by the

men, such as clothes and tobacco. These buildings were not very well built, as they were

often meant to be temporary, to be moved when the trees were gone. Each camp typically had

two foremen, about seventy men, twenty teams of horses and seven yoke of oxen. The men

came to the camp in late fall or early winter, as logging was a cold weather job. The food

was plentiful, if boring. The usual meal would be bread, potatoes, tea, beans and pork.

The crews worked from about 4 a.m. until dusk, even eating the noon meal in the woods. The

horses and oxen, on the other hand, were very well treated and rarely overworked.

Source: Unknown

Evidence of loggers still remains in the woods of early 21st century Michigan, as

evidenced by this white pine monolith in the woods near Otsego Lake. For some

reason, the tree was "notched" but not felled. Later, fire

scorched the stump.

Source: Photograph by Randy Schaetzl, Professor of Geography - Michigan

State University

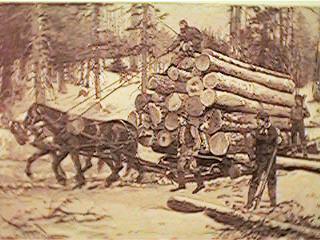

Next, how were the logs transported to the river? Usually, in winter, the logs

were transported via sleds, pulled by horses.

Source: Unknown

The logs were far too big and heavy to take from the woods by dragging, so the loggers

made ice-covered roads, where the logs could be pulled on sleds.

Source: Unknown

Source: Unknown

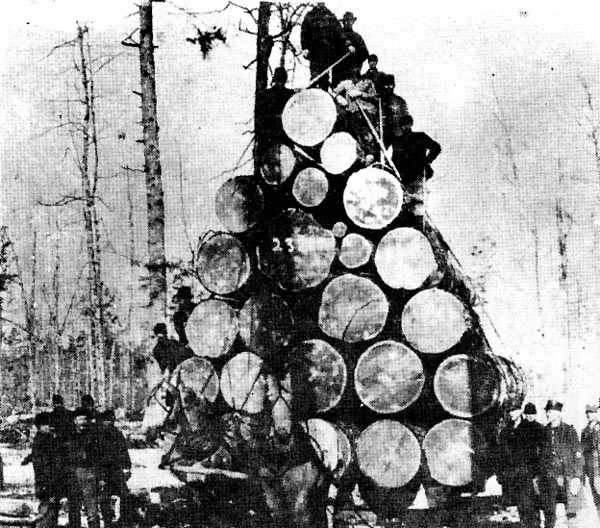

The loads were often extremely big and contests were held between rival camps to see which

could stack a load the highest. The logs were taken to the banks of rivers, where they

were piled twenty to thirty feet high, awaiting the spring thaw. When rivers melted, the

logs were pushed into the swollen rivers and floated to the mills. At the mills, the logs

were sorted in the boom area, each identified by a log mark on the end of the logs. They

were then sorted in the boom area, each company’s logs together.

When the winter season was well advanced the log hauling began.

The roads were plowed of snow and sprinkled with water; they then froze into smooth,

glassy ways. Over these the logs were hauled on sleds from the skidways to the rollways.

The cutting went on through the winter season until the trees were all felled, or the

spring thaws ruined the roads. By spring the last log was in place, the melting snow

flooded the creek, the rollways were "broken out" and the drive was on.

Source: Unknown

The sled tracks had to be iced down, so that they would slide easily. Thus, it was

the job of some men to, every day, go to the river, load up on water, and take the water

to the logging roads. These roads were then "iced down", so that the next

day logging could proceed easily. Below is an image or two of just such an ice sled,

filling up with water (see the barrel of water being pulled out of the iced-over river?).

Source: Unknown

Nicely iced logging roads allowed lumberjacks to load up and haul tremendously large loads of logs. Images below illustrate this point well.

Source: Unknown

Click here for full size image (290 kb)

Source: Unknown

Be aware that most of the time, the sleds were never loaded this high--it took too much

time and was too dangerous. These images were set up and posed, for show.

Source: Unknown

The image below illustrates not only how full these logging sleds could get, but also what

intensive logging did to the previously-forested landscape!

Source: Unknown

Many people wonder and ask, "How did the loggers ever get the logs up so high onto a

sled?" The image below may give you a hint.

Source: Unknown

The increased lumber production during the final decades of the 19th century was due in

part to changes in machinery and techniques which brought greater efficiency to the

industry. Throughout the first half of the 19th century lumbering had been a

weather-dependent and seasonally limited enterprise. Cutting was done during the winter

when timber could be pulled on large sleds, if there was snow, from where the tree had

been felled to banking grounds (rollways) along a river.

The river drive was also dependent on a good winter snowfall for it was

the spring runoff, which enabled the rivers to carry the huge pine logs to the sawmills at

the mouths of the rivers. Log drivers were usually men who had spent the winter in the

woods cutting timber. It was their job to control the flow of the river by building and

breaking dams and to break up log jams they could not prevent.

Sawmills were most often located at the mouths of the driving rivers.

Associations were formed to cooperate in the sorting of logs into a pond or bay where

floating "booms" of logs separated the property of one company from that of

another. From the booms logs were floated to the mills to be sawed.

Greater mill capacity coupled with a continuing demand for wood also

put pressure on the loggers to cut as much as possible each season. A number of small

changes improved the efficiency of woods operations somewhat. These included the

substitution of the cross-cut saw for the axe in felling timber and the replacement of

oxen with horses as sled teams.

Some of the images and text on this page were taken from various issues of Michigan History magazine.

This material has been compiled for educational use only, and may not be reproduced without permission. One copy may be printed for personal use. Please contact Randall Schaetzl (soils@msu.edu) for more information or permissions.