The first inhabitants of the Great Lakes

basin arrived about 10,000 years ago. They had crossed the land bridge from Asia or

perhaps had reached South America across the Pacific Ocean. Six thousand years ago,

descendants of the first settlers were using copper from the

southern shore of Lake Superior and had established hunting and fishing communities

throughout the Great Lakes basin.

One of the ways that the Indians would manipulate copper was with

"hammer stones." These hammer stone were found near prehistoric copper

diggings in the Keweenaw Pennisula. They are prehistoric tools used

3000-5000 years ago. The Indian "miners" would build a fire over the

copper vein which would heat the rock around the copper. After heating they

would pour cold water on it to crack the rock. Then they would pound out the

copper with rock hammers and stone chisels. These hammers usually had a

handle attached to them. Some hammers were held with the hands and

were not grooved. When they broke they tossed them aside. Grooves were

put in the hammers with smaller stones. The hammers are found today,

underground, anywhere from 6" to 3'. It is hard work digging for them.

The copper was shaped into spear points, arrow heads, knives, harpoons, and

jewelry.

The native people occupied widely scattered villages and grew corn,

squash, beans and tobacco, and harvesting wild rice. The state’s indigenous

peoples--its first true farmers--supported themselves through a combination of hunting and

gathering and simple agricultural techniques. Their modest plots produced corn, beans,

peas, squash, and pumpkins. However, the Indians used only a portion of their holdings for

crops and so caused few lasting changes in the countryside. They moved once or twice in a

generation, when the resources in an area became exhausted (GLERL 1995). Those not

in villages were scattered throughout the beautiful but inhospitable pine forests of the

north. Villages were relatively impermanent and, except in two or three very populous

areas, widely separated from one another. The crude and primitive means of subsistence

that the Indians had at their disposal seriously limited the number that a given area

could support. The greatest concentration of population coincided almost perfectly with

the area of deciduous forest. Maple and birch were the two most valuable trees: the first

for its sugar, the latter for housing material and canoes. Other sources of food supply,

such as game, wild apples, plants, and berries, as well as land suitable for agriculture,

were more likely to be found in the deciduous than in the coniferous forest lands.

A majority of Indian settlements were along waterways, as in the St.

Joseph and Saginaw River valleys--then the two most populous areas. Water provided an easy

means of transportation and, in fish, a plentiful supply of food. Some settlements along

the Lake Michigan and Lake Superior shores were regularly occupied in summer and abandoned

for more sheltered positions in winter.

When Etienne Brule', the first white man to set foot on Michigan soil,

landed at the site of Sault Ste. Marie in 1620 (see image below), the population of

Michigan was about 15,000. The southern half of the Lower Peninsula accounted for about

12,000. Others have estimated that the population of Native Americans in the Great

Lakes was between 60,000 and 117,000 in the 16th century, when Europeans began their

search for a passage to the Orient through the Great Lakes. Some estimate that 10% of all

the Indians north of the Mexico border lived in Michigan, at the time of first contact

with Europeans.

Etienne Brule is the first European to see Lake Huron

Native American Indians were the first to use the many resources of the Great Lakes basin. Abundant game, fertile soils and plentiful water enabled the early development of hunting, subsistence agriculture and fishing. The lakes and tributaries provided convenient transportation by canoe, and trade among groups flourished. By about A.D. 100, Native American inhabitants of the Upper Peninsula (Ojibwes) were using improved fishing techniques and had adopted the use of ceramics. They gradually developed a way of life based on seasonal fishing which the Chippewas/Ojibwes still followed when they met the first European visitors to the area. Scattered fragments of stone tools and pottery mark the location of some of these prehistoric lakeshore encampments.

Source: Unknown

The above picture shows Native American Indians at a camp on Mackinac Island in 1870. The picture is a bit misleading, however, since most Native Americans in the Great Lakes region lived in hogans or wigwams like the one shown below, not in teepees.

Source: Unknown

Today, evidence of these ancient cultures is meager. Some of the paleo-Indians left burial and other ceremonial mounds behind, like these in SW Lower Michigan. (Note the gravel pit in the foreground.)

Source: Pictorial History of Michigan: The Early Years, George S. May, 1967.

Archeologists often find their projectile points and arrowheads, indicating sites where they hunted or camped for extensive periods of time. But for the most part, evidence of Native American cultures in Michigan is not great.

Source: Pictorial History of Michigan: The Early Years, George S. May, 1967.

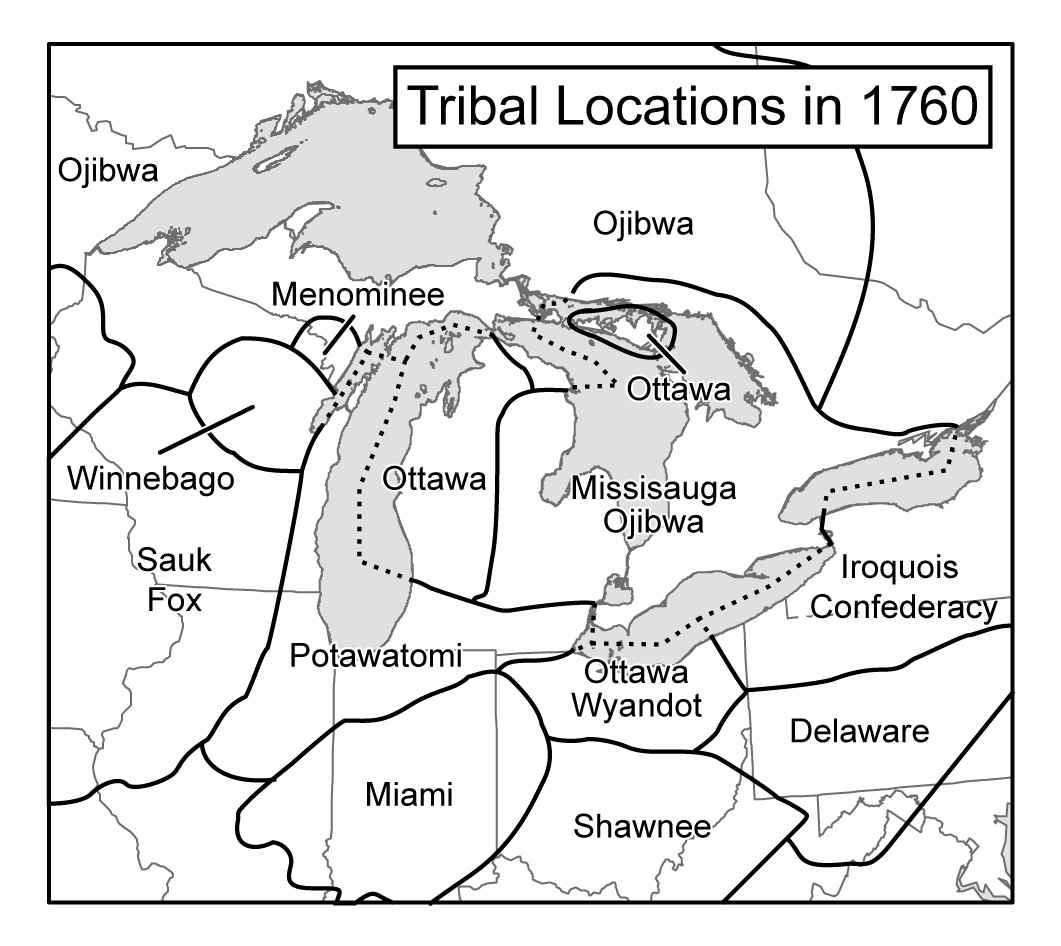

Native Americans lived and traveled primarily along water routes and water bodies.

Thus, as of about 1670, much of the dry inland areas of Michigan were essentially

unoccupied (see map below). Inland Michigan was used almost exclusively for travel, not to live. It was a place to cross, not to

live.

The Woodland Indian Tribes of the Great Lakes area and throughout the eastern and southern

part of the United States were farmers. In the fall and winter they hunted and trapped,

moving in small family groups to winter hunting camps. Beaver, muskrat, raccoon, deer,

elk, bison and black bear were taken for the meat and hides. In the spring, the Indians

made maple sugar in large quantities. It was a staple in their diet. They also harvested

nuts, berries, wild plums, wild cherries, and pawpaws. Wild rice was gathered around the

Great Lakes. Corn, beans, squash, and pumpkin were widely grown in North America, north of

Mexico. Besides multi-colored Indian corn the Indians developed varieties of eight and

ten-row corn. Beans grown by the Indians included the kidney bean, navy or pea bean,

pinto, great northern marrow, and yellow eye bean. The Indians planted corn and beans in

the small mounds of soil and often pumpkins, squash, or melons in the space between.

Many other vegetables were grown by the Indians: turnips, cabbage, parsnips, sweet

potatoes, yams and "Irish" potatoes, onions and leeks. Watermelon and muskmelon

were introduced into North America in the 17th century and were being grown in the

interior within a few years. The nature and extent of Indian agriculture are

revealed in the observations of George Will, a soldier in General Anthony Wayne's campaign

against the Indians along the Auglaize and Maumee Rivers (Ohio) in the summer of 1794.

"Here are vegetables of every kind in abundance," Will wrote, "And we have

marched four or five miles in cornfields down the Oglaize [sic], and there is not less

than one thousand acres of corn around the town."

When the first French explorers pushed into Michigan, early in the 17th century, the

country was inhabited by Indians of Algonquin stock. This family embraced a large number

of tribes in the northeastern section of the continent, whose language apparently sprang

from the same mother tongue. It was Algonquins who greeted Jacques Cartier, as his ships

ascended the St. Lawrence. The first British colonists found Algonquin Indians hunting and

fishing along the coasts and inlets of Virginia. It was Algonquins who, under the great

tree at Kensington, made the covenant of peace with William Penn, and when French Jesuits

and fur traders explored the Wabash and the Ohio, they found their valleys tenanted by the

same far-extended race. In the 1700's travelers might have found Algonquins pitching their

bark lodges along the beach at Mackinac, spearing fish among the rapids of St. Mary’s

River, or skimming the waves of Lake Superior in their canoes.

The Algonquin had resided in Michigan for at least a century before the

coming of the whites. Who preceded them, no one knows, although certain archeological

finds suggest the bearers of the Hopewell culture, which is now extinct.

Source: Pictorial History of Michigan:

The Early Years, George S. May, 1967.

The chief tribes in the Michigan region in the late 1700's were the Chippewa,

or Ojibwa, occupying the eastern part of the Lower Peninsula and most of the UP; the Ottawa,

in the western part of the Lower Peninsula; and the Potawatomi, occupying

a strip across the southern part. None of these tribes, apparently, had exclusive

possession of the section it occupied. The Saginaw Valley, in the very midst of the

Chippewa terrain, was the stronghold of the Sauk. The Mascoutin

had a precarious hold on the Grand River Valley, until the Ottawa, having driven them from

the Straits of Mackinac, subsequently drove them beyond the borders of the present State.

The Miami, in the relatively populous St. Joseph River Valley, shared a

similar fate at the hands of the Potawatomi. Other subtribes that once dwelt in the

southwestern part of the State were the Eel River, the Piankashaw, and the Wea, while the

Menominee, established in the wild-rice country of Wisconsin, included a part of the Upper

Peninsula in their domain.

The Algonquin peoples and their descendants were an agricultural people and

depended more upon producing vegetables than upon hunting. In Michigan, corn was the

staple foodstuff, although wild rice, which was common throughout the State in mud-bottom

lakes and sluggish streams, tended to take precedence in the northwestern, especially

around Green Bay. Corn was often planted in the midst of the forest--the trees having been

killed by girdling, to admit the sunlight--together with squash, tobacco, and kidney

beans.

Corn was stored for the winter in cribs--similar to those of the

present-day American farmer--and in pits (caches) in the ground. Corn, like the land

itself, was the property of the family or clan. So deeply ingrained was this notion of

communal ownership of land that, when later the Indians agreed to "sell" it to

the whites--oftentimes several thousand acres for a barrel or two of whiskey--they assumed

they were simply granting permission for joint use and occupation of the land. It was

beyond their comprehension that land could be fenced-off as private property.

To the Europeans, the Indians owed, in addition to spirituous liquors and tuberculosis,

the extension of the practice of scalping. Taking the scalp lock of vanquished foes had

long been a rite among virtually all North American tribes; but, because it was a

difficult operation with crude stone knives, it was, perforce, held within limits.

Europeans brought steel knives and offered bounties for scalps especially during the War

of 1812, when Chippewa sided with the British. Thus, in much the same way that the

Michigan Indians were transformed from an agricultural to a nomadic hunting people by the

European demand for furs, they were transformed from a peaceful to a warlike race by the

French and English demand for scalps.

The basic political unit of the Indians was the tribe, consisting of people speaking the

same dialect, occupying contiguous territory, and having a feeling of relationship with

one another. The chief was elected to hold office until he died or the electorate became

dissatisfied with his leadership and chose another. Often a son was chosen to succeed his

father. Besides the chief, there were other dignitaries, notably the priests, and advisory

council of minor chiefs, and sometimes a special war chief.

Within the Indian community it was customary for the women to do the

gardening, cooking, and housekeeping; and the men engaged in hunting, fishing, tool

making, and, when necessary fighting. Medicine was the exclusive province of the

priesthood, who also officiated at burials. These consisted either of interment near the

village, without a marker or with houses of bark and wood over the graves, or of interment

in mounds, large and small.

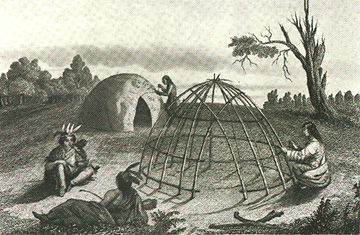

The Indians of Michigan were housed in dome-shaped bark- or mat-covered

lodges in winter, and in rectangular bark houses in summer. Among the Chippewa, the summer

residence was the conical skin or bark-covered tepee, popularly associated with Indians in

general. Homes were furnished with wood and bark vessels, some splint basketry, woven bags

for storage, reed and cedar-bark mats, and copper tools and utensils; a hole in the roof

permitted egress of smoke from the cooking fire. Native pottery was of a primitive order,

as was work in wood, stone, and bone.

The men wore leggings, breechcloths, and sleeved shirts--all made of

animal skins; while the women wore skirts and jackets of the same material. Moccasins were

soft-soled, with drooping flaps. Robes of skin served for additional protection during

cold weather and as blankets at night.

Besides mining copper, the natives quarried stone to a certain extent,

although a great deal of the stone for arrowheads and spearheads came from other areas,

chiefly Ohio. Some was imported from beyond the Rocky Mountains. Michigan cherts and

flints are generally drab in color, course-grained , and often marred by fossils,

blemishes, and flaws. The richest source of supply was around Saginaw Bay. Heavy stones

for axes were plentiful along the banks of streams and lakes. A gray stone, from which

pipes were made, is reported to have been quarried in the vicinity of Keweenaw Bay.

The attitudes toward the Indians have changed greatly since the 1800's.

The text below is taken from an 1880 history text, in which the Indians in

south-central Michigan were being characterized:

Of the character of the Indians of this region: "They were

hospitable, honest, and friendly, although always reserved until well acquainted; never

obtrusive unless under the influence of their most deadly enemy, intoxicating drink. None

of these spoke a word of English, and they evinced no desire to learn it....I believe they

were as virtuous and guileless a people as I have ever lived among, previous to their

great destruction in 1834 by the cholera, and again their almost extermination during the

summer of 1837 by the (to them) most dreaded disease, smallpox, which was brought to

Chesaning from Saginaw, - they fully believing that one of the Saginaw Indians had been

purposely inoculated by a doctor there, the belief arising from the fact that an Indian

had been vaccinated by the doctor, probably after his exposure to the disease, and the man

died of smallpox. The Indians always dreaded vaccination from fear and suspicion of the

operation.

"The Asiatic cholera in 1834 seemed to be all over and was

certainly atmospheric, as it attacked Indians along the Shiawassee and other rivers,

producing convulsions, cramps, and death after a few hours. This began to break up the

Indians at their various villages. The white settlements becoming general, and many

persons selling them whisky (then easily purchased at the distilleries for twenty-five

cents per gallon), soon told fearfully on them. When smallpox broke out in 1837 they fled

to the woods by families, but not until some one of the family broke out with the disease

and died. Thus whole villages and bands were decimated, and during the summer and fall

many were left without a burial at the camps in the woods, and were devoured by wolves. I

visited the village of Che-as-sin-ning - now Chesaning - and saw in the summer-camps

several bodies partially covered up, and not a living soul could I find, except one old

squaw, who was convalescent. Most of the adults attacked died, but it is a remarkable fact

that no white person ever took the disease from them, although in many instances the poor,

emaciated creatures visited white families while covered with pustules. Thus passed away

those once proud owners of the land, leaving a sickly, depressed, and eventually a

begging, debased remnant of a race that a few years before scorned a mean act, and among

whom a theft was scarcely ever known. I do not think I possess any morbid sentimentality

for Indians. I simply wish to represent them as we found them. What they are now is easily

seen by the few wretched specimens around us."

"

This material has been compiled for educational use only, and may not be reproduced without permission. One copy may be printed for personal use. Please contact Randall Schaetzl (soils@msu.edu) for more information or permissions.