The early residents of Michigan were great travelers. Travel by water especially was common, a natural circumstance in an area with an extensive coast line. To most Native Americans, travel was by birchbark canoe, along lakes and rivers. Hence, few Indians actually lived in many of the upland, dry parts of Michigan. Rather, these were areas that were simply "passed through". The rivers maintained a regular flow, in those days, because of the standing forest, and the light Indian canoes could be propelled to their uppermost reaches. By paddling to the source of an eastward-flowing river, leaving the water for a short portage, and descending a westward-flowing river, the Indians could, and regularly did, cross the State at several places. The portages were used later by their European successors.

Source: Unknown

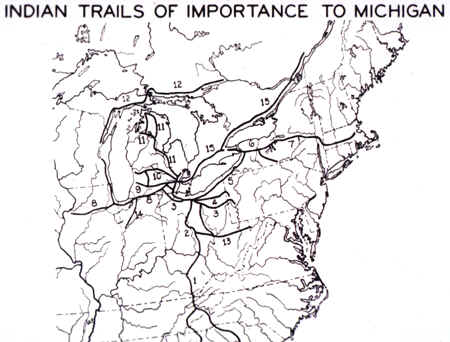

An even more important legacy was the network of Indian trails, which

became the routes by which French and English fur traders, and settlers from New York, New

England, and Virginia, penetrated the forests. Some still survive as modern highways,

notably the Saginaw Trail from Toledo through Saginaw to Mackinac, part of which forms the

modern Dixie Highway; the Grand River Trail between Detroit and Grand Rapids, whose route

is now followed by the trunk line US 16; the St. Joseph Trail out of Detroit, now known as

US 12 and I-94, and the Sauk Trail, which followed roughly the line of present US 112

between Detroit and Chicago. The Upper Peninsula was traversed from northeast to southwest

by the Sault and Green Bay Trail, the course of which is now followed by US 2 and State

Rte. 35. From these major thoroughfares branched numerous minor trails; and many of these

also persist as state and county roads.

Internal migrations (within the region) were so common that one person

has compiled a map (below) showing the major migrations within the region, that were

commonly undertaken.

Source: Unknown

Along the many Indian trails, archeologists have been able to identify

over 1,000 mounds, 80 enclosures and embankments, 30 so-called ‘garden beds.’

750 village sites, and 260 burying grounds. Other material cultural remains include

evidences of prehistoric copper mining in the Keweenaw Peninsula and on Isle Royale and a

host of miscellaneous artifacts, such as arrowheads, hammers, knives, drills, hoes, spade,

pipes, fragments of pottery, and large and small effigies in stone.

Discoveries that have been made, however, indicate that mound building

was a rather general practice among the aboriginal inhabitants, the purpose being usually

interment of the dead. By far the greatest number of mounds have been discovered in the

southern half of the Lower Peninsula, in a triangle having the Indiana-Ohio boundary as

its base and the head of Saginaw Bay as its apex.

One of the largest mounds was on the Rouge River, at what is now

Delray. As described by Bela Hubbard, in his Memorials of Half a Century, it was 40

feet high and several hundred feet long. It gave evidence of having been used for burial

by successive generations, and possibly by successive tribes, as the soil containing

skeletons was evidently stratified. Some mounds formed effigies, many of which were

serpentine in shape; others were surrounded by enclosures, or associated with them.

Enclosures usually consist of circular or elliptical embankments, from

2-5 feet in height, about an area of one acre or slightly more. Sometimes they are

surrounded by a moat, hence the belief that they may have been forts. Some show evidence

of not having been used for more than 250 years. In addition to the mounds and enclosures,

ditches and pits, large and small, are among the most common earthworks as yet

undestroyed. The pits were most frequently used for cooking and for storage, some yielding

up kernels and ears of corn preserved from decay for years, perhaps centuries.

Source: Unknown

There is an ancient highway in Northwestern Lower Michigan. Native

American artifacts and campsites can be found along the trail. Artifacts and burial mounds

were also found. In one area along the trail near Mesick, approximately 50 mounds were

found. Near Buckley, 150 circular fire pits were discovered by US Forest Service

personnel.

Those who travel its fading lanes often find themselves on a journey

that leads them back in time. Faded and worn stone markers remain at certain sections of

the trail to point the way down the old highway which has nearly been lost in the pages of

time. The evidence that it was also an old stagecoach route is that there are tracks of

wagon wheels found along certain parts of the trail. Information available at the forest

service also states that a silver oxidated cross, which is believed to have belonged to a

Jesuit priest was found at Buckley. A sword and pieces of metal that resembled armor were

additional relics obtained at the site. Records indicate that a sword and armor found at

the location may possibly have been from the french explorer La Salle, who is known to

have visited St. Joseph, Michigan at one time.

Trails were not haphazard undertakings which merely followed deer

trails, but were part of an elaborate statewide highway system used by Native Americans.

Trails like the Cadillac to Traverse City trail were used for long distance travelling.

The Indians who built them were not just people who were wandering around, they knew where

they were going. There was a trail network that crisscrossed the entire state.

There was an economy in how they chose a trail. These trails were used

for regular transportation. They were established by criteria. The trails weren’t

just for 25 year old men, there were entire families walking them. The paths followed the

areas of least resistance, and crossed rivers where they were the shallowest.

Forest service records indicate that the trails were so systematically

planned that they later became modern highways. Mackinaw Trail in Cadillac, and parts of

U.S. 131 are examples.

After the settlers arrived, the Native American travel-ways became

stagecoach highways.

For a more regional look at the major Indian trails, see the map below.

Source: Unknown

Parts of the text above have been paraphrased from C.M. Davis’ Readings in the Geography of Michigan (1964).

This material has been compiled for educational use only, and

may not be reproduced without permission. One copy may be printed for

personal use. Please contact Randall Schaetzl (soils@msu.edu)

for more information or permissions.