INDIAN LAND CESSIONS

The status of the Indian tribes under American law was that

of nations within a nation. Each of the treaties with Indian tribes was subject

to the approval of the United States Senate, just as were treaties with foreign

countries.

What is now Michigan was included within the territories

ceded to the United States by Great Britain in 1783. But the land

of Michigan was the property of the Indian tribes and was legally recognized

as such. It remained the property of those tribes until it was ceded to the

United States by treaty.

The tradition of peace among the Indian tribes of the

Great Lakes region was rudely shattered with the penetration of the French

and English into the West. Even before the period of actual white settlement,

tribal boundaries had shifted as a result of pressure from the Iroquois on

the east and the Sioux on the west. The Sauk, reduced in numbers, combined

with the Fox and withdrew to Illinois; the Mascoutin and Miami were banished

from the region. The Wyandot (or Huron), an Iroquoian tribe east of Lake

Huron, were swept from their holdings by other tribes of Iroquois, united

in the famous Five Nations. They fled to various parts of the north in 1649

and, in 1680, settled around Detroit.

Before settlers could legally obtain any land,

the government first had to persuade the Indian tribes to relinquish their

claims to the land. To the American pioneer, the Indian had no positive effect

on the economy. As the fur trade declined and agriculture took its place

as the mainstay of Michigan’s economy, the Indian became a barrier to the

exploitation of the area’s land resources. What the Michigan pioneers wanted

was the Indian’s land; what became of the Indians was of no concern to them.

To the land-hungry pioneers who poured into Michigan during the early 19th

century, the Indian was not a romantic figure. He was a nuisance. Bullets,

rum, and treaties, hardly worth the paper their terms were written on, were

used without compunction to rid Michigan of its Indians and open the land

to the farmer, the road maker, and the lumberman. Of all these methods the

treaty was the most effective. The commissioners who negotiated the treaties

may have intended to treat the Indians fairly, but, more often than not,

their recommendations and promises were altered by a Congress less concerned

with the needs of the aborigines than the demands of would-be settlers and

land speculators. In almost every instance, the Government failed to live

up to its obligations. Later, the natives were rounded up without benefit

of treaty, and conducted, under military escort, to lands beyond the Mississippi.

The "American era" began auspiciously. Although the Ordinance

of 1787 provided for the government of the old Northwest Territory, of which

Michigan was a part, that government seemed remote and indifferent. British

influence kept the Indians uneasy and sullen, and there were few American

settlers in the region.

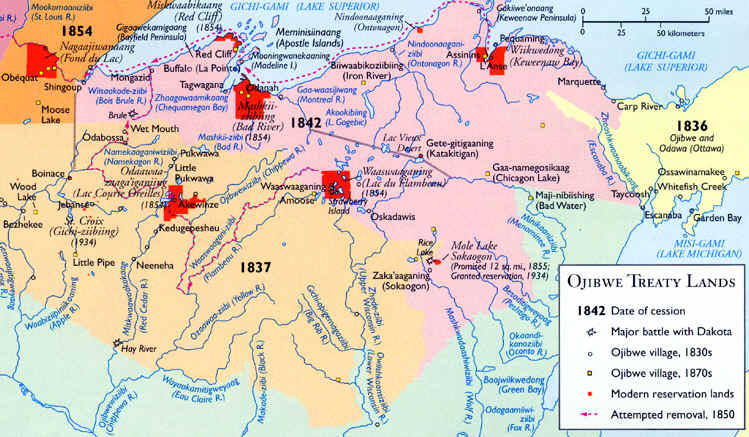

The first Michigan lands were obtained from the Indians

by the Treaty of Greenville in 1795, and a much larger tract had been secured

by the Treaty of Detroit in 1807. The Treaty of Greenville called for

the cession of a tract 6 miles wide extending from Lake St. Clair to the

River Raisin, as well as Mackinac Island, Bois Blanc Island, and other important

lands. The next cession in 1817 was of a small area along the Ohio

border just west of the lands described in the treaty of 1807. Under the Treaty

of Saginaw, signed in 1819, an immense tract in the northeastern sector of

the Lower Peninsula was ceded. By the terms of the Treaty of Chicago in 1821

most of the land in the southwestern part of the Lower Peninsula south of

the Grand River was acquired, while the northwestern section of the peninsula

and the lands in the Upper Peninsula to the east of the present city of Marquette

were ceded in the Treaty of Washington in 1836. Most of Alger County, in

the central UP, was included in the lands ceded by the Chippewa to the United

States government in 1836. The Chippewa retained reservations on Grand Island

and in the Munising area until 1855. In spite of attempts to move them west

of the Mississippi, most of the Alger County Chippewa remained in the Upper

Peninsula, and some of their descendents still reside in the county today.

By the time Michigan was admitted to the Union in 1837, only the western

part of the Upper Peninsula and a few tracts that had been "reserved" for

the Indians had not been obtained. The final major cession, involving the

western Upper Peninsula, came with the Treaty of La Pointe in 1842.

The 1842 Treaty ceded an area rich in copper and iron in

northeastern Wisconsin and the western UP of Michigan. This "Copper Treaty"

allowed mining companies to exploit the ore bodies. Although Native Americans

had carried out small-scale copper mining for centuries, the Ojibwe who signed

the treaty were more interested in retaining their ways of life elsewhere.

Source: Atlas of Michigan, ed.

Lawrence M. Sommers, 1977.

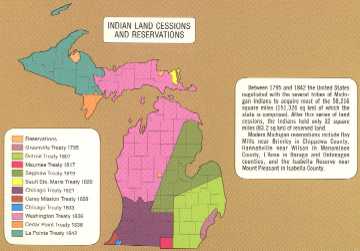

The completion of a canal around the Soo Rapids facilitated the copper rush

into the region in the late 1840s. The map below shows the dates and

areas of the various Indian cessions in Michigan, in their entirety.

Click here for full size image (255 kb)

Source: Atlas of Michigan, ed. Lawrence M. Sommers, 1977.

The story of the Treaty of Saginaw illustrates the manner in which

these Indian land cessions were often secured. The incentive for the treaty

came from individuals who had visited the Saginaw Valley, believed the area

had a great future, and hence were ambitious to secure lands for settlement

or speculation. They made their desires known in Washington, and Michigan’s

Governor Cass was then instructed to negotiate the desired treaty. Cass then

sent word for the Ottawa and Chippewa to meet with him near the junction of

the rivers flowing into the Saginaw. The date set was the full moon in September,

a time when the Indians had gathered their harvests but before they had set

out on winter hunting. Two ships were loaded in Detroit with provisions and

liquor for distribution at the proper time, and soldiers were put aboard

to protect the negotiators. A council house, which consisted of a roof of

boughs supported by trees, the sides and ends left open, and in the middle

a long platform with rustic benches for Cass and the other officials, was

constructed at the site. Cass arrived on September 10, 1819, with a staff

of assistants and interpreters. Preliminaries lasted for about two weeks,

during which time anywhere from 1,500 to 4,000 Indians assembled. Cass started

with a lengthy speech, with necessary pauses for translation by interpreters.

In his remarks he made known the extent of the lands that he desired to purchase.

Indian orators replied at length, and meanwhile the Indians pondered the

question of whether they would cede their lands.

The tract Cass proposed to buy from the Indians consisted

of some six million acres---nearly one-sixth of Michigan’s total land area.

The Indians would receive a lump sum of $3,000 in cash, and an annual payment

of $1,000 plus "whatever additional sum the Government of the United States

might think they ought to receive, in such manner as would be most useful

to them." The government also agreed to furnish the Indians with the services

of a blacksmith and to supply them with farming implements as well as teachers

to instruct them in agriculture.

The treaty was then signed. To celebrate the occasion,

Cass authorized five barrels of whiskey to be opened and the contents distributed

among the natives.

It is not entirely correct to assume that the US paid the Indians

little or nothing for their land. Up to 1880 the total cost to the United

States government of the public domain acquired from the Indians amounted

to $275 million, and the surveys of the land cost another $46 million. Total

receipts from the sale of these lands to that date were $120 million less

than these expenditures. The Indians received for their lands cash, goods,

and promises, and often the government agreed to pay annuities to a tribe

over a period of years.

INDIAN TREATIES WITH THE U.S. GOVERNMENT

(Between 1795 and 1842, Michigan Indians essentially gave up the state.)

TREATY NAME DATE AREA OF CONCERN

Greenville 1795

Detroit area.

Detroit

1807 Southeast Michigan.

Maumee

1817 Most of today’s Hillsdale County.

Saginaw

1819 Alpena-Lansing and east

Sault Ste. Marie 1820 Eastern Chippewa

County in U.P.

Chicago I 1821

Southwest corner of Michigan. Equivalent in size to Detroit treaty of 1807.

Carey Mission 1828 Most

of today’s Berrian County in the extreme southwest corner of Michigan.

Chicago II 1833

In today’s Berrian County

Washington 1836

Western half of northern lower peninsula of Michigan and the upper peninsula

east of and including Alger and Delta Counties.

Cedar Pint 1836

Today’s Menominee County and part of Delta County.

La Point

1842 The upper peninsula west of Alger and Delta Counties.

Ojibwe cessions

At first, American settlers avoided the northern Ojibwe

country, preferring the farming areas to the south. The Canadian Shield underlies

most of the region, which has mainly infertile soil, conifer forests, swamplands,

acid granite bedrock, and shallow, rocky soils. That combination did, however,

make it inviting for resource extraction, and soon the appeal of this land

prompted Americans to go after it with as much zeal as other lands in Michigan.

When forced migration of Indians began, some escaped to Canada, while others,

in scattered bands, moved north or west before the advancing settlers. The

remaining Chippewa, Ottawa, and Potawatomi gravitated toward the Upper Peninsula

and the northern part of the Lower Peninsula, where, for a while, the pressure

upon them was less intense than in the more densely populated counties. Here

the broken remnants of the tribes endeavored to adjust themselves to their

altered status. They did odd jobs and made souvenirs; they fished and hunted,

usually to supply their own needs, sometimes for commercial profit. Many

retired to a dispiriting existence on reservations, which, until a recent

date, were indifferently managed.

This material has been compiled for educational use

only, and may not be reproduced without permission. One copy may be

printed for personal use. Please contact Randall Schaetzl (soils@msu.edu)

for more information or permissions.