THE ERIE CANAL

The Erie Canal: Facilitating Travel TO Michigan

Regardless of the prevailing views of Michigan’s land and climate,

a more important factor is delaying any large-scale movement into Michigan in the

immediate postwar years was the difficulty in reaching the territory.

Transportation to Michigan by water was "dangerous, unreliable, and fraught with

discomfort." Navigation on Lake Erie was regarded as more dangerous than on the

Atlantic. Accommodations for passengers were poor. To reach Detroit from the south by land

it was necessary to cross the Black Swamp in northwestern Ohio. In rainy

periods the swamp was virtually impassable. The horrors of the Black Swamp were widely

publicized. At a time when plenty of good land was still available in Ohio, Indiana, and

Illinois, there was little incentive for the pioneer to brave the hazards involved in

getting to Michigan.

The completion in 1825 of the Erie Canal (below),

connecting Lake Erie with the Hudson River, was an event of major importance in Michigan

history because it greatly facilitated the transportation of passengers and freight

between the eastern seaboard and Michigan ports.

Source:

Unknown

The canal, built by the state of New York at a cost of $7 million, was such a success that

within three years toll charges had paid the cost of construction plus interest charges.

For the first time, New England families, anxious to leave rocky and infertile fields for

richer lands in the West, had a route for reaching the "promised land."

Furthermore, the waterway provided not only an easier way to move to Michigan but access

to markets in the East. Freight rates between Buffalo and New York were reduced from $100

a ton to $25 a ton with the opening of an all-water route between the two cities, and the

rates soon fell even lower.

Important as it was, the Erie Canal did not cause the great migration

to Michigan; it only facilitated that movement. This is shown by the fact that

public land sales at Detroit reached a high point in 1825, the year the Erie Canal opened,

and then declined in the years immediately following. Whereas 92,232 acres had been sold

in 1825, sales were down to 70,441 by 1830.

The Erie Canal, in New York state (shown below), was 360 mi (580 km)

long, and connected New York with the Great Lakes via the Hudson River. Locks were

built to overcome the 571-ft (174-m) difference between the level of the river and that of

Lake Erie. It opened in 1825.

Source: Unknown

Source: Unknown

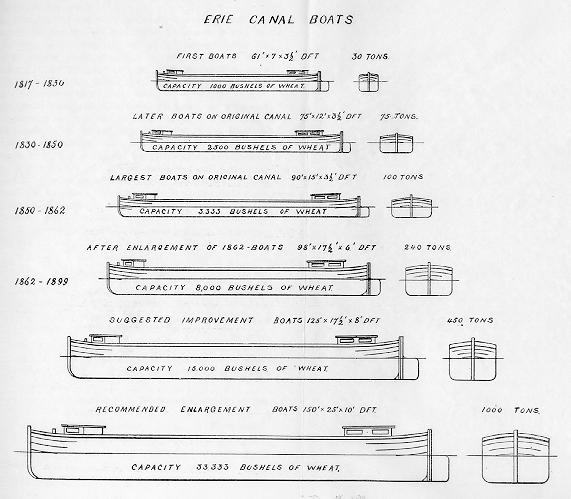

In its early days, the canal was not very large (see below), but it was large enough to

move Michigan's grain and wool east, thereby providing Michigan with a market for it's

commodities, which rapidly fueled the influx of settlers.

Source: Unknown

The boats used on the Canal were generally flat-bottomed, and usually hauled grains, wool, whiskey, and sometimes meat.

Source:

Unknown

Land Transportation

For the improvement of land transportation within the territory, Michigan relied heavily

on the federal government. In 1816 troops of the Detroit garrison began building a road to

the rapids of the Maumee River, near the present city of Toledo. By 1819 it was "cut

through" and bridges over rivers and marshes had been built, but the road was still

poorly located and almost impassable for wagons. A road across the Black Swamp from the

settled part of Ohio to the Maumee Rapids was completed the same year. Thus, by 1827 land

transportation to Detroit from the south had been greatly improved.

Roads from Detroit into the interior were required, however, before any

large-scale settlement of Michigan territory was possible. In 1816 the territorial

government launched a project to build a road northward from Detroit, but the road was

inadequate and by 1822 had reached only as far as Pontiac. A post road from Pontiac

through Flint to Saginaw was laid out in 1823. Intervening swamps made progress difficult.

The first road westward also was a military road, designed to connect

Detroit with Fort Dearborn. It followed the path of the Old Sauk Trail and is the

approximate route of the present US 12. It ran westward from Detroit to Ypsilanti, then

veered to the southwest, and continued through the southernmost tier of Michigan counties.

The eastern portions of this road were in use by the latter 1820s, and by 1835 two

stagecoaches a week operated between Detroit and Fort Dearborn. This highway, known then

as the Chicago Road, became "practically an extension of the Erie Canal and...a great

axis of settlement in southern Michigan". Another road westward was known as the

Grand River Road. It generally followed the route of the present I-96 freeway, and in

places is still known as "Grand River Avenue". It followed an old Indian

trail.

These roads were a far cry from their modern counterparts. It can

hardly be said that they were "built" at all, as we think of highway building

today. Surveyors selected the route, often following Indian trails, axemen cut away the

brush and felled trees low enough along the path so wagons could pass over the stumps, and

workman constructed crude bridges over streams which could not easily be forded. Logs were

laid across the road over bogs and swamps to prevent wagons and animals from miring. This

was known as a "corduroy road". Other than this, little was done to provide a

surface for the roads. They were notoriously bad.

Settlers along the roads took a proprietary interest in the mudholes,

and the right to pull wagons out of one of them for a price was recognized as belonging to

the man who lived nearest to it. It was said that these mudholes were fostered

carefully in dry weather; one tavern keeper found a buyer for his property partly, it was

said, because he had nearby an especially profitable mudhole.

Since the roads were laid out to follow the routes having the fewest

obstacles, they were seldom straight. A description of the Chicago Road stated that it

"stretches itself by devious and irregular windings east and west like a huge serpent

lazily pursuing its onward course utterly unconcerned as to its destination.

Bad as they were, these roads were of utmost importance in the early

settlement of Michigan. Trails branched off along the routes followed by the major roads,

which served to guide the traveler to a destination beyond the main roads. Along the chief

roads taverns were built and towns sprang up.

Finally, by the end of the 1820's, with the relinquishment of Indian

claims to the lands in southern Michigan, the rapid progress of the surveys, the opening

of land offices, and the improvement of transportation facilities, the way had been

prepared for what shortly developed into one of the great land booms in all of American

history as settlers poured into and across the lower third of Michigan’s southern

peninsula.

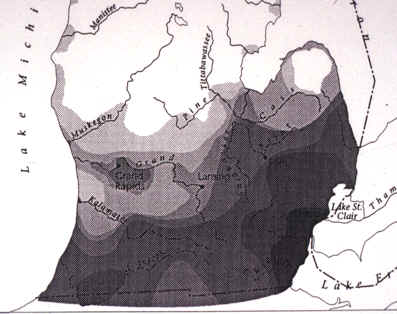

The map below shows the tremendous influx of settlers to the state during the early

1800's, especially in the 1830's.

Source:

Unknown

And below is a close-up of that map for the southernmost part of Michigan.

Source:

Unknown

The majority of the newcomers came by way of the Great Lakes, making the journey from

Buffalo to Michigan by steamship or sailing vessel. Detroit was the major point of entry.

Some settlers landed at Monroe and a few at smaller ports on the east, while some, seeking

land in western Michigan, went by lake vessel around the Lower Peninsula, landed at St.

Joseph or other ports on Lake Michigan, and proceeded from there into the interior.

Sizable numbers came northward overland from Ohio and Indiana into the southern counties

of Michigan. Some used the "Michigan Road," which the federal government built

between Madison, Ohio, and the foot of Lake Michigan.

Below is an excerpt I found on the web. It's an e-conversation between two people.

I found it interesting:

Q: I am interested in any information anyone might have

one how the ancestors got from WESTERN NEW YORK to MICHIGAN in the mid 1800's. I have

heard that some came over the lakes once they froze over. Many of our ancestors roots are

originally in New York, how did they get here??

A: One relation of ancestors that I have been able to track found

their way to Hubbardston, Ionia County. Angeline and her husband arrived in Hubbardston,

Michigan in 1854. They came by way of the Erie Canal to Buffalo, NY, and then sailed on a

ship to Detroit. From Detroit, they took the railroad to Owosso, Michigan, where the

railroad ended. From there they caught the work train from Owosso to Saint Johns and then

traveled by oxcart to Plains. They stopped at a friend's house in Matherton for two weeks

before going on to Hubbardston. They lived there for two years fighting malaria. Then they

bought and cleared land in Bloomer Township, in Montcalm County two miles away form the

then-non-existent Carson City, where Angeline pulled her end of a crosscut saw and had to

contend with Indians who were numerous.

Some of the text on this page was adapted from Dunbar and May's Michigan A History of the Wolverine State.

This material has been compiled for educational use only, and may not be reproduced without permission. One copy may be printed for personal use. Please contact Randall Schaetzl (soils@msu.edu) for more information or permissions.