Economic prosperity due to the logging industry in Michigan was breeding ecological disaster. Timber waste, forest fires, and a total lack of interest in conservation practices all contributed to the devastation. A great fire in 1871, for example, damaged the entire Lake Michigan shoreline, destroyed the cities of Holland and Manistee, and spread across to Port Huron. By 1900, the lands of the northern Lower Peninsula and the eastern Upper Peninsula were stripped of pine, and scores of lumber towns were dying.

Fire has played a major role in shaping vegetation patterns. Native Americans set fires to clear wooded areas and improve wildlife habitat for hunting. European settlers suppressed brush fires, causing forests to replace some large prairies. Wasteful timber-cutting practices led to disastrous forest fires, including the deadly 1871 Peshtigo fire. In the early lumbering days, more timber was lost to fire than was actually harvested. Today, wildfires still affect the logging, tourism, and recreational industries. Most fires strike between March and November; they occur particularly often in drought years.

Forest fires were a part of the logging scene in Michigan, although not necessarily the result of it. Nor were forest fires new to the state at the time logging began. Extensive burned-over areas were reported by early surveyors long before the lumbermen arrived. But the great influence of people during the logging era, and the large areas of dry pine slash increased both the possibility of fire and the intensity of those which occurred. Many reached tremendous proportions, burning unchecked for weeks or months through slashings, standing timber, cities and settlements, causing human misery, death, and waste. There is evidence to show that these lumbering era fires destroyed more merchantable timber than was cut. Most of the pine areas in the north part of the Lower Peninsula have burned over at least once, and many several times. Fires were not confined to pine lands, for hardwood slashings also burned. Large parts of these once charred lands are now occupied by jack pine, oak, aspen, and white birch, species which form much of the young forest growth found in northern Michigan.

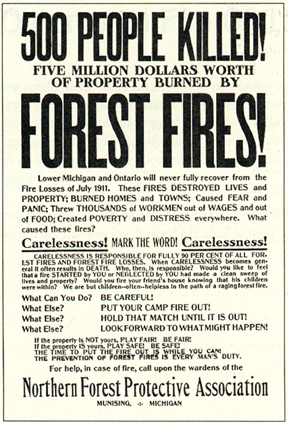

Forest fires have posed a danger throughout Michigan history, particularly in times of drought. The wasteful practices of the early timber industry worsened the hazard by leaving behind huge amounts of dry wood and brush piles.

After decades of logging activities, Michigan was littered with thousands of hectares of slash--dead branches, leaves, and wood. In their haste to move on to new cutting sites, loggers usually gave little thought to the lands they were leaving. By the 1870s stumps and branches already littered much of northern Michigan. There was no longer any barrier to erosion on cutover land, and the dried debris created an enormous fire hazard. At the end of the dry summer months fires frequently broke out, sometimes moving into still uncut timberlands or settled areas, as in 1871 and 1881, when fires broke out across the state.

Upon drying, these became highly flammable, and led to innumerable fires. Many of

these fires were immense, covered large areas, and burned for days. The scene below

shows an area near the Upper Manistee River after an 1894 fire.

Source: Unknown

Source: Unknown

Michigan’s first catastrophic fire was in the autumn of 1871. However, the

hundreds of lives lost in fires in Chicago and northeastern Wisconsin at the same time

overshadowed Michigan’s losses. A combination of numerous small and large fires, the

1871 fire swept across the Lower Peninsula, destroying Holland, Manistee and several

Saginaw Valley towns and leaving an estimated 20 dead. A decade later, in September 1881,

the Thumb was ravaged by fires that took 282 lives, blackened a million acres and cost

$250,000 in property damage.

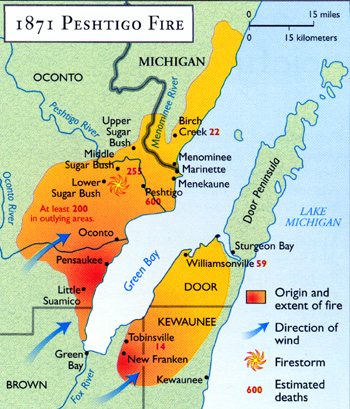

The 1871 fires

Let's start with the first big fires in the region--which also happen

to be the most famous and the largest! Inevitable disaster occurred in the drought

year of 1871. On the night of October 8, hot winds from the south caused normally

controllable small fires to shift suddenly and gather force. They swept through a 60-mile

stretch north of Green Bay, Wisconsin and a 50-mile stretch on the Door Peninsula, and

collectively became known as the "Peshtigo Fire." The conflagration claimed an

estimated 1,200-1,500 lives. Survivors later told of jumping into rivers to escape the

flames, and witnessing firestorms, or "tornadoes of fire," that devastated

enormous areas. Many of those who sought shelter in the Peshtigo River literally

boiled to death.

Source: Atlas of Wisconsin

On October 8, 1871, at about the same hour, two devastating fires started, one in rural

Peshtigo, Wisconsin, the other in downtown Chicago. Both fires remain today among

the worst natural disasters to befall the Midwest. In fact, no forest fire since the

Peshtigo disaster has taken more lives; and the Chicago fire remains the most

destructive metropolitan blaze in the

nation's history, having caused some $200,000,000 in property damage and all but

obliterating the city's core.

The Great Chicago fire caused an estimated 250 deaths. Numerous fires on Michigan’s Lower Peninsula also started on October 8, 1871, at places like Holland, Lansing, and Port Huron (see map below). Because they started during the day, the Michigan fires claimed fewer lives, though they destroyed more land and timber. Newspapers of the time publicized the Chicago fire widely, making it the most infamous of the three disasters. The Peshtigo Fire stands today as the deadliest forest fire in modern world history.

Source: Unknown

The Holland fire, like the others, was due to a combination of high winds and extremely

dry conditions. The heart of the Dutch settlements in western Michigan (at Holland)

shared the same kind of disaster that struck Chicago, Illinois, October 8 and 9, 1871. At

the time, Holland was a small, insignificant town in comparison to Chicago, but for the

Dutch immigrants in Michigan, the "Colony at Holland" (pop. 2400), as it was

first known, was the focal point for religious refugees who had come in 1847.

A devastating economic tragedy, the fire of 1871 nearly wiped out the

town founded by the Rev. Albertus C. Van Raalte. The results of hard work of 24 years were

practically wiped out in the early morning hours of October 9. But it was also a disaster

for the concept and vision that brought the Dutch to western

Michigan. Although the basic concept was fading into the background when the tragedy

occurred, the ideas which brought the village into existence were still operative in the

functioning of the town. Fortunately the fire impeded the growth and development of De

Kolonie only temporarily.

Most of the townspeople were Dutch immigrants, but a mixture of native

Americans was evident by the fact that two lodges functioned in the town (to which Dutch

immigrants by religious conviction did not belong), and some English speaking

congregations, such as Methodist and Episcopal, had been organized. The Dutch were members

of either the predominant Dutch Reformed Church or the True Reformed Church which broke

from the Dutch Church in 1857. All in all, Holland was a very flourishing little city that

had a harbor and new rail connections, making it a natural market for all the outlying

agricultural districts.

A period of extensive drought preceded the fire of 1871. Several fires

had broken out around the town before October 8, and Hope College had been threatened only

a week before. An added hazard was the cut timber and brush that lay in the woods

surrounding the town. The old river bed and ravine along Thirteenth Street behind the

Third Reformed Church was filled with such debris. The situation became critical on Sunday

afternoon, October 8, when a southwesterly wind began to build up in intensity. The

townspeople turned out en masse to fight fires that were flaring up on the southern

and southwestern part of the town even though that first alarm sounded during the time of

the afternoon church services. Disaster was upon the town with the development of

"hurricane" winds in the evening. Any thought of saving the town was forgotten

when two major structures on the west side caught fire. Within the space of two hours the

fire took its toll. "The entire territory covered by the fire was mowed as clean as

with a reaper; there was not a fencepost or a sidewalk plank and hardly the stump of a

shade tree left to designate the old lines," said one resident.

Although the disaster was nearly total, the recovery was rapid, and

Holland today is a thriving city in its own right.

The 1881 Thumb fire:

The fire of 4-6 September 1881, commonly known as

the Thumb Fire, burned well over one million acres, cost 282 lives, and did more than

$2,347,000 damage. The fire destroyed a major part of Tuscola, Huron, Sanilac, and St.

Clair counties. It consumed 1,531 houses and 1,480 barns and outbuildings, and left

14,448 homeless. Like the 1871 fire, the fire of 1881 came at the end of an

extremely severe drought and was the result of hundreds of land-clearing fires whipped

into a cauldron of flame by high winds. In the Saginaw Valley and the Thumb region it

burned over much the same territory that had been burned by the 1871 fire. This fire, 10 years previous, had been so strong that winds associated with it had

blown over trees, and many of these were still laying around, dry. Also, 1871 fire

did not consume all the slash left by the logging operations of the previous decades, so

much was left to burn. No one is sure just how or just where in Tuscola County the

fire started. It was the time of year when people used to burn brush piles and other

debris left by lumbermen and those engaged in clearing the land. Many people think the

wind may have whipped a brushpile fire out of control. The fire probably started as

a series of small blazes in slash fires coalesced into a wall of flame moving to the NE.

Its severity is accounted for not only by the drought and high winds that

prevailed, but by the fact that the country was full of slash from logging and land

clearing, and of dead and down timber killed, but unconsumed, by the fire of 1871.

The appalling thing about this loss of life was the large number of children

involved due to whole families being wiped out. One detailed account of the fires

that burned in the Thumb is given in a report of a man who traveled over the burned area

after the fire and interviewed many of the survivors. He emphasizes the extreme dryness

that prevailed, the presence of vast areas of logging slash, the debris left by the fire

of 1871, the prevalence of land-clearing fires, and the occurrence of winds of hurricane

force, all of which combined to produce the holocaust which resulted. There have been bad

fires in Michigan since, but none as severe or extensive as the great fires of 1871 and

1881.

Source: Photograph by Randy Schaetzl, Professor of Geography - Michigan State University

Persons who have not experienced a big forest fire cannot conceive of the appalling

conditions which occur and the terror and helplessness of those in its path. The following

excerpts from contemporary accounts give some idea of the conditions that prevailed in the

1881 fire:

From the Evening News, Detroit: Thursday, September 1, 1881:

"The drought all over the Mississippi Valley and throughout the

northwest continues with unabated rigor. Atmosphere scorches and blisters

everything...vegetation dried to a cinder, gives nothing but material for fire. Trees

shedding their leaves a month before the usual time; grass brown and withered. Pastures

and streams dried up. Milk scarce, butter a luxury. If it does not rain and rain hard

soon, food will be scarce this winter...Buyers paying the unheard price of 18 and 20 cents

a pound for butter."

Saturday, September 3: "Farmer near Stark

overcome while fighting fire and burned to death."

Tuesday, September 6: "Women burned to death

while fleeing for shelter near Lapeer...terrible fires reported raging in the forests

northwest and north of Bay City...air full of cinders... people suffering from heat and

smoke...Fires devastating the woods around Flint."

"Saginaw: Intensely warm and smoke

suffocating. East of the city forest fires raging fiercely. ...hundreds of acres afire.

Fires plainly visible from the city at night...

"Detroit: Heat and drought almost

unprecedented. Throughout the timber regions great forest fires are raging in all

directions from the Mississippi to the ocean. In many places the earth is so dry that

fires have penetrated into the soil, following the vegetable fibers and moving

mysteriously by this means over many miles only to break to the surface in a destroying

conflagration wherever the surface vegetation furnishes fuel. (Fires) seem to break out

spontaneously from the bosom of the earth.

"Port Huron: Tremendous fires in Sanilac and

Huron counties...Richmondville destroyed and Deckerville reported burned... Many people

horribly burned."

Source: Unknown

Wednesday, September 7, 3:00 p.m.: "Wholesale

devastation in Saginaw Valley and Huron peninsula. Entire townships becoming roaring

furnaces and let in ashes.., Over 30 lives lost...survivors fleeing to the lake.

4:00 p.m.: "At least 100 lives lost in

Sanilac County alone. Men, women and children burned on the roadside while seeking

shelter.

Friday, September 9: "The worst ever:

Thirty-one townships and 11 villages swept by the flames...45 bodies found near Paris in

Sanilac County...fire started in NW part of Sanilac County and in adjoining Huron County

from settlers burning to clear land...spread east and north to the lake shore, then west

through Huron County, then south and southwest, then east across Cass River where it met

another part of the fire and raged for twelve hours...500 to 600 dead, 2,000 families

homeless, 15,000 destitute."

An intimate account of conditions is found in the story told by a

Reverend of the First Baptist Church of Harbor Beach, who said: "At sunrise, Monday, September 5, the air was clear. By 1:00 pm the sky was

copper colored. At 2:00 it was so dark that lanterns were necessary out of doors to find

one’s way around. Darkness continued all afternoon. Many thought the end of the world

was at hand. Terror heightened by the approach of flames, the stories of destruction to

the west, and the arrival of charred remains and refugees. This continued until Wednesday

morning, when at 8 am the wind changed to north and brought relief."

Said one, a resident of Minden City, speaking to a local reporter three

days after the flames subsided, "By six o’clock the people

began coming into Minden from the west, having barely escaped with their lives, and when

morning arrived hundreds had found their way here in a half-nude condition, burned and

blinded by the smoke. We then began to have a faint realization of the extent of the fire.

Then we first understood that not property alone, but human lives had been swallowed up.

To the west and north the roads were lined with the carcasses of horses, cattle, sheep,

swine and poultry, etc., cooked and charred almost to a crisp. Then human beings, also

cooked and charred, were found. Some were still alive, with the feet, hands and face

literally baked. Some had their ears and nose burned off, and their eyes almost burned out

of their sockets. It is too horrible to contemplate!"

Farmers along the Cass River fled to the water for safety as the fire

rolled over them, again and again. They saved their lives, nothing else. Cinders and ash

fell into the river. The water was so hot the fish died and floated on the surface by the

hundreds.

The fire appeared at Bad Axe, 20 miles northeast of Cass City, a little

after 1:30 p.m. Monday. The winds had begun at noon and, according to observers, trees

were broken off at the stump, boulders rolled along like pebbles, and people lifted off

their feet into the air. Above the wind, a strange roar was heard, the sound of the

approaching flames. Shortly after 1 pm there was darkness, as though a curtain had fallen.

Four hundred people fled to the new brick courthouse. As they watched,

building after building burned around them. Thirty men pumped water from the adjoining

well and kept the walls and tile roof wet. After a few minutes they had to return inside

because of the heat, and another 30 would take over. Across the street, barrels of

kerosene and gunpowder ignited when the hardware store burned. The store turned dark, then

blew into a bright, red glare.

Thirty townsfolk made it east to a plowed field on W.F. Thompson’s

farm, the fire gaining on them. They dug a ditch and covered it with boards and blankets.

While the women and children remained under cover, the men took turns keeping the blankets

wet.

"It grew so dark at Zinger’s Hotel at

12 noon," said William Bope, "that they were

obliged to light lamps." At about 1 p.m. the wind changed and blew at

hurricane force from the west. At the same time the fire started all over the large

clearing in small patches of blue flame. In every direction small fires could be seen

starting up. By 1:30 a solid wall of flame, from 50 to 100 feet high, was sweeping from

the west over Paris. At nearly every house, women and children were out in the road,

wailing and wringing their hands in despair. The smoke was so dense that nothing could be

distinguished 300 yards away. The fire seemed to burn everywhere at the same time, as

though it dropped from the clouds. The sky looked like one sheet of flame.

Hundreds found refuge in wells while the flames passed over. Others

survived by reaching an open field and burying their faces in the dirt to breathe. They

dug holes with their hands, lay face down in ditches or waded out into a river or the

lake. Survival was often a matter of chance. In Paris Township, where 23 bodies were found

the first night, the fire traveled 10 to 20 mph, the speed of a running man. "Horses

did gallop before it, but were overtaken and left roasting."

Many bodies were found untouched by the flames, killed by suffocation,

smoke inhalation and the heat. Some survivors died later of burns and inflammation of the

lungs. "The heat from the flames was so intense,"

Said William Bailey, stationed at Port Huron, "that sailors

felt it uncomfortably even though the hot air had moved over the cold water of Lake Huron

a distance of seven miles. It withered the leaves of trees two miles from its path. Whole

fields of corn, potatoes, onions and other growing vegetables that were not touched by the

flames, roasted by the heat."

Monday night the winds abated. Fires burned across the entire area from

Saginaw east to the lake where the walls of flame had passed, "lighting

up the heavens." Tuesday night the winds reversed and pushed the fires back

over the burned districts. Heavy rains late Wednesday put an end to most of the burning,

but the suffering and afflictions had only begun.

Flames leapt to treetops and raced along on strong winds. The fire

raced northeastward to the lake shore at the tip of the Thumb. Then winds shifted to the

west and the fire spread eastward through Sanilac and St. Clair counties.

Mr. Spencer recalls how farmers in the Deford area (at the boundary of

Tuscola and Sanilac counties) saw the fire coming and thought the end of the world was

upon them. He tells of how minutes before the fire reached his parents’ farm, and

while the wall of flame was more than a mile away, a large stump in the middle of a

cleared field suddenly burst into flames.

Wild animals took refuge in buildings with humans. Men put women and

children into wells. Some people escaped by wading into rivers and covering their heads

with wet blankets. Those who lived near the lakeshore took refuge in the waters of Saginaw

Bay and Lake Huron.

Mr. Spencer recalls that a neighbor’s team of oxen came through

the fire alive but lost their hooves; that another neighbor turned six hogs loose and

never found a hair of them...but did find six large grease spots several yards from where

he had released them.

The fire acted queerly, it seemed to those early Thumb residents.

Flames would engulf one building and suddenly extinguish themselves while destroying other

buildings nearby.

One neighbor was sure all would be lost in the fire. This man boarded

up all openings to his barn, then slit the throats of all his livestock and ended his own

life with a shotgun. He was found later, after fire passed by and left his buildings

untouched.

"To realize how these fires could be so destructive and

extensive one must understand the condition of most of the unimproved land in Huron

County. The fires of 1871, which were so general, converted a great portion of the green

woods into windfalls.

"All of the timber (consisting largely of pine, hemlock and cedar

with some hardwoods) on thousands and thousands of acres fell down and were piled and

interlocked in every shape in impenetrable masses. It has been a common remark that there

would yet be another fire greater than the one which caused these windfalls before they

could be gotten rid of. During these ten years something has been done towards cleaning

them up. Large quantities of cordwood and timber had been taken from them.

In spite of the horror and devastation brought to the inland portions

of the county, an optimistic item appeared in the Caseville locals-no doubt read with some

bitterness by those who suffered in the fire: "Although bringing misery to so

many, we can hardly realize at present the great benefit the country will derive from the

fires in the near future by rendering the land more available for settlement. Everything

will progress with rapid strides. Railways will be pushed through; a tide of immigration

will pour in; farming and pasturage will be largely engaged in and in ten years from now

the country will be 50 years ahead."

Click here to go to part II of this page on Michigan's post-logging fires.

Note: some of the text and images in this section have been paraphrased and taken from Betty Sodders' book, "Michigan on Fire", and from various issues of Michigan History magazine. Finally, parts of the text above have been paraphrased from C.M. Davis’ Readings in the Geography of Michigan (1964).

This material has been compiled for educational use only, and may not be reproduced without permission. One copy may be printed for personal use. Please contact Randall Schaetzl (soils@msu.edu) for more information or permissions.