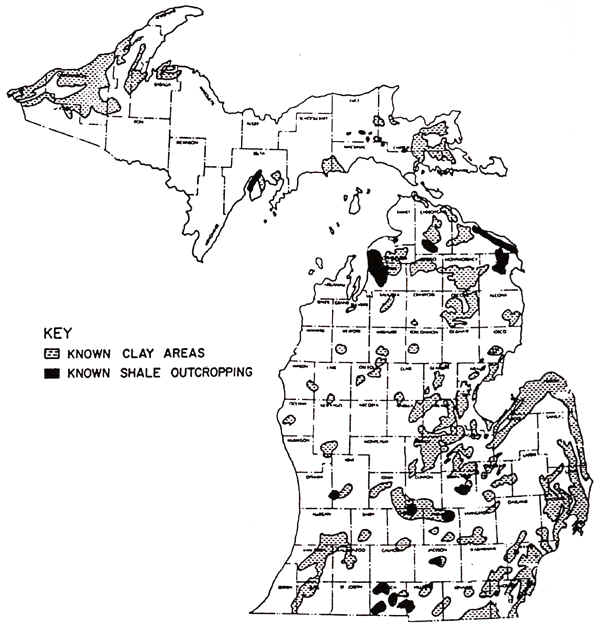

Clay is an important raw material in the manufacture of bricks; in fact, it is the main raw material in such manufacturing. Michigan produces many millions of tons of bricks annually. The clay for these bricks comes from two sources: clayey sediments laid down in glacial lakes, and shale bedrock. The map below shows where such locations exist in the state.

Source: Unknown

Shale was originally deposited in shallow waters of the Michigan basin, as clay. It

eventually hardened into shale. Clays laid down by the receding ice sheets primarily

were deposited in the deepest waters of proglacial lakes.

The black Mississippian shale, the

Antrim shale, the green Ellsworth shale, and the blue Coldwater shales are very useful in

the manufacture of cement, brick and tile. Quarries are worked in them in Alpena,

Charlevoix, Antrim and Branch counties.

The mining, production and uses of cement, clay and shale are

quite similar. Cement is made from shale or clay, and limestone. The term

"cement" is most often used to refer to Portland cement. Portland cement, when

mixed with sand, gravel, and water, makes concrete, which is an essential element of the

construction industry. Portland cement accounts for more than 95% of all cement produced.

To make Portland cement, clay, shale and limestone is ground to a powder and baked in a

kiln. The baked mixture forms clods (clinkers), which are then ground up and mixed with

gypsum. Most of the raw materials are mined in open pits. Michigan traditionally ranks in

the top five states in terms of cement production. One of the largest cement plant in the

state is in Alpena. Making Portland cement requires lots of heavy raw materials and a

tremendous amount of energy.

Source: Unknown

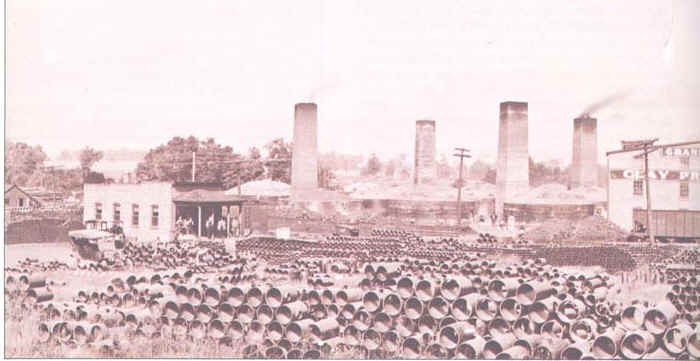

Clay is also used to make pottery and tile (clay pipes). The city of Grand Ledge

has a history of manufacturing based on clay as a raw material.

Until it closed, Grand Ledge Clay Products remained an old-time

industry, retaining many of the methods and equipment that were used decades ago. For the

first 35 years of its operation, Grand Ledge Clay Products manufactured conduits for

underground telephone wires. Chicago was a prime market for that product, and many a

street in Chicago still has Grand Ledge tile underneath it. These telephone

conduits---hollow, pipe-like tiles, see below---were also used as building materials. The

plant’s horse livery, built in 1908 and later used as a garage, had mortared conduit

tile for its foundation and walls. Other houses and buildings in Grand Ledge also were

made of the tiles whose ends were often filled in with cement.

Source: Image courtesy Michigan History Magazine

In 1937 a fire razed the factory building, destroying the molds that

were used to make the conduits. Then the market for clay drain tile declined, and the

company shifted production to agricultural drain tiles, chimney tops and sewer pipe

fittings.

The process used to produce tiles has not changed much over the years.

Nearly all the raw material----actually a shale, not a clay----was mined from the

property. In the early days, horses pulled railway carts full of the soft rock from open

pits to the factory; later, a small locomotive did the job. The chunks of shale were then

ground and sifted into a fine granular powder that was mixed with water to form a soft

clay. The clay was then forced down through a bore and extruded through a die to form

tiles.

The fragile, "green" (unbaked) tiles were dried and then

transported to the kilns. Firing took from 50 to 140 hours, depending on the thickness of

the tiles. Vitrification occurred at 1860-1940 degrees F, the temperature at which clay

particles liquify slightly and are thus bonded together.

For many years, salt was added during firing to create a glaze on the

tiles that made them less permeable to water. However, testing proved that salt also

weakened the tile. After the conversion to gas firing, which allowed more precise control

of firing times and temperatures, better vitrification could be achieved, and glazing was

no longer needed.

Grand Ledge Clay Products was not the only such industry in Grand

Ledge. Across the street, the American Sewer Pipe Company (later the American Vitrified

Company) took advantage of the rich subsurface deposit from which fine clay products could

be made. That deposit, called the Saginaw shale, is an extensive formation of soft,

layered rock that was deposited in the quiet waters of an ancient ocean. These rocks are

well known for preserving fossils of the prehistoric ferns and trees. Coal, the

concentrated carbon residue from the partial decay of those swamp plants, is also found in

the area.

Saginaw shale is a mixture of fine silt and sand particles. Although

harder to work with than most deposits used in the clay industry, it made an extremely

fine product. With a large, rich deposit of high quality raw material and decades of

successful operation, why did Grand Ledge Clay Products close? Part of the reason can be

stated in one word----plastic. Plastic sewer pipes and drain tiles have largely replaced

their clay counterparts. Lansing and Flint were two of the last cities in Michigan to

still use clay sewer pipes.

Because of the slackening demand for clay sewer pipe and tiles,

production at Grand Ledge Clay Products in the late 1960s and early 1970s moved to chimney

flue liners. In the early 1980s, a series of new plant managers introduced the manufacture

of veneer tiles and paving bricks. Although the spotted bricks were very popular, it took

some time to discover that architects were the key customers for them. By the time that

discovery was made, the company’s capital was exhausted. Rather than renovate the

plant, the stockholders decided to close and liquidate its stock.

The presence of Grand Ledge Clay Products will not be easily erased.

Acres covered with hills of unused clay form a desolate, eerie landscape behind the

factory---a miniature badlands. The stream beyond flows over pottery shards, so much a

product of this land that they seem to belong there. Near the stream, huge old sewer pipes

have been captured like spools on a stick by 20 year-old poplars growing through their

center.

Some of the images and text on this page were taken from various issues of Michigan History magazine.

This material has been compiled for educational use only, and may not be reproduced without permission. One copy may be printed for personal use. Please contact Randall Schaetzl (soils@msu.edu) for more information or permissions.