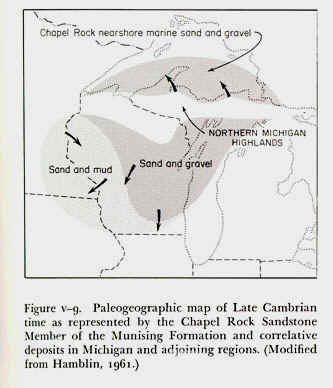

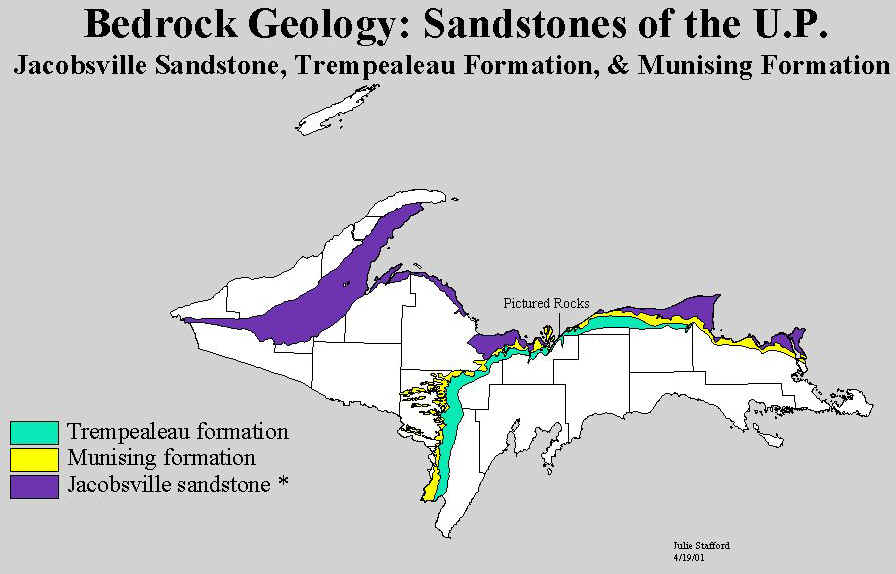

The first of Paleozoic seas, during the Cambrian period, received coarse sandy sediments from swift streams flowing southward from bare highlands to the north. The shore line was somewhere in the Lake Superior trough, and to the west, somewhere near the central part of Keweenaw County. The rocks representing Cambrian time are mainly sandstones, and cover large parts of the UP (see map below).

Source: Michigan State University, Department of Geography

As much of the sediment was derived from the iron formations in the west they range in

color from a deep dark red to mottled red and white, buff, white, and gray. Towards the

end of Cambrian time the sediments became finer, the sea shallower, and its shore farther

south; the sediments were clear white sand.

The Cambrian sandstones were, thus, the first rocks laid

down on the Precambrian basement.

Hamblin, W.K. 1961.

Paleogeographic evolution of the Lake Superior region from Late Keweenawan

to Late Cambrian time. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 72:1-18.

They are important reservoirs of groundwater in the Northern and Southern Peninsulas. The

red Jacobsville Sandstone, a good building stone, was formerly quarried at Jacobsville and

used for building purposes until shipping costs and cheaper cement-concrete materials made

production costs prohibitive. Michigan has large reserves of sandstone in the Peninsula.

Near the top of the AuTrain formation the sandstone is free enough of impurities to make

it a potential source of glass sand. At present probably the tourist receives greatest

value from the sandstone in viewing the scenic effects produced by weathering along

exposed edges at the lake shore, and in the little gorges cut back into the cliffs by

rivers--Pictured Rocks, Miner’s Castle, Miner’s Falls, and many others.

The Ordovician-St. Peters sandstone is also a good water reservoir (aquifer).

The Cambrian sandstones near Picture Rocks National Lakeshore.

Source: Michigan State University, Department of Geography,

used with permission.

The fossils suggest that the climate again became genial at the close of the Silurian, the seas warm, and the sea creatures returned to the region. Silurian time totaled 25 million years.

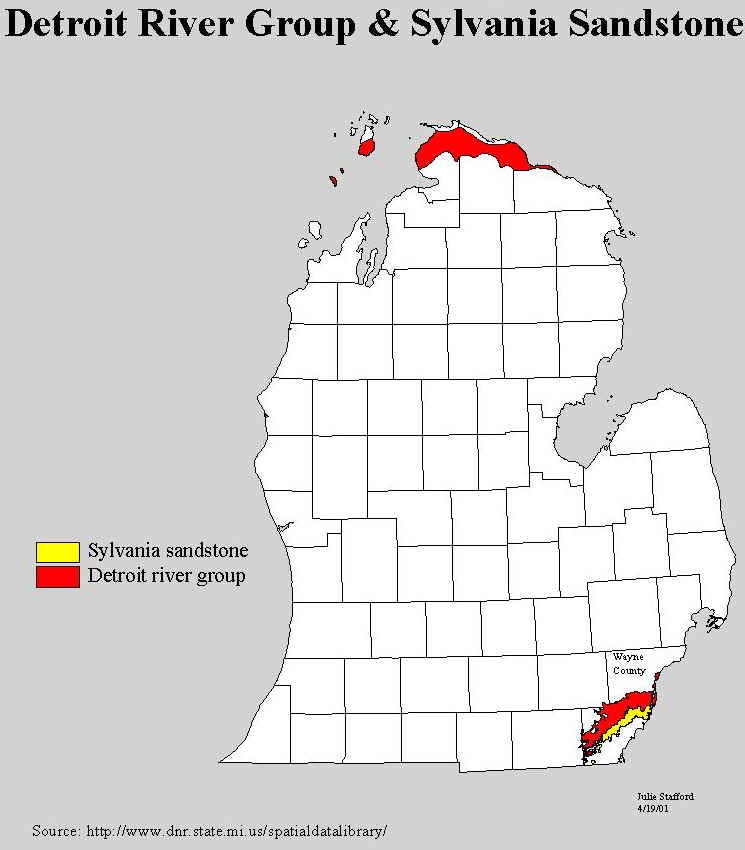

The climate changed to warm and moist in the Devonian period, which was to last 35

million years. Michigan was almost an enclosed pool of the Devonian sea and the northern

shore of the sea was somewhere in Lake Michigan across the St. Ignace Peninsula into

northern Lake Huron basins. A part of the southeastern shore cut diagonally across Monroe

County from northeast to southwest. On the southeastern shore sand dunes were whipped up

by the Devonian winds and are now beds of white sandstone --- the Sylvania. Spreading deep

into the basin from the southeast, layers of sand and lime and salt were deposited which

became the formation we know term the Detroit River formation.

The Sylvania Sandstone

Devonian rocks supply a variety of mineral resources. A

Devonian sandstone formation known as the Sylvania Sandstone located at or near the

surface in Wayne and Monroe counties contains high silica, uncontaminated sand grains.

Source:

Michigan State University, Department of Geography

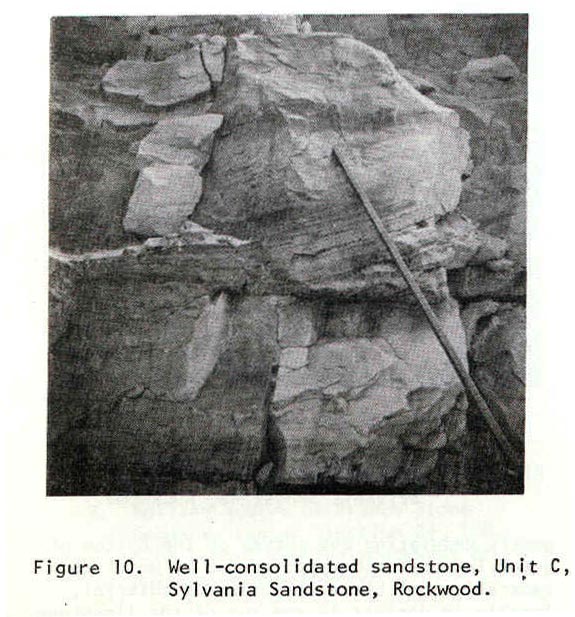

Mining sandstone involves different techniques (i.e., blasting, crushing, etc.) and the

process is more expensive. However, the requirements of the glassmaking industry for

high-silica sand with negligible contaminants motivate the operators to mine the

sandstone, even at great expense.

Source:

Unknown

From the outcrop of the basal Sylvania sandstone in Wayne and Monroe

counties we obtain sand used in the manufacture of glass. Some of this sand is so free

from iron, the most vexing impurity, that the sand is suitable for optical glass. During

and shortly after World War I most of the glass used for the manufacture of optical glass

for the federal government was obtained from the Michigan quarries. The sand is now used

for the manufacture of plate glass, fine table glassware, and common glassware of many

uses. These sandstone beds are believed to be ancient dunes blown up on the shore of an

ancient Devonian sea. As we trace the Sylvania towards the center of the Michigan Basin,

we find from the logs (records) of wells drilled into it that it becomes thicker with

lenses of limestone and shale, and that the porous parts of the formation contain brines.

These brines are in use as brine reserves for chemical industries, and also possible oil

and gas reserves.

At its close the Devonian seas became shallow and were bordered by

low-lying lands from which sluggish rivers brought sediments black with decayed

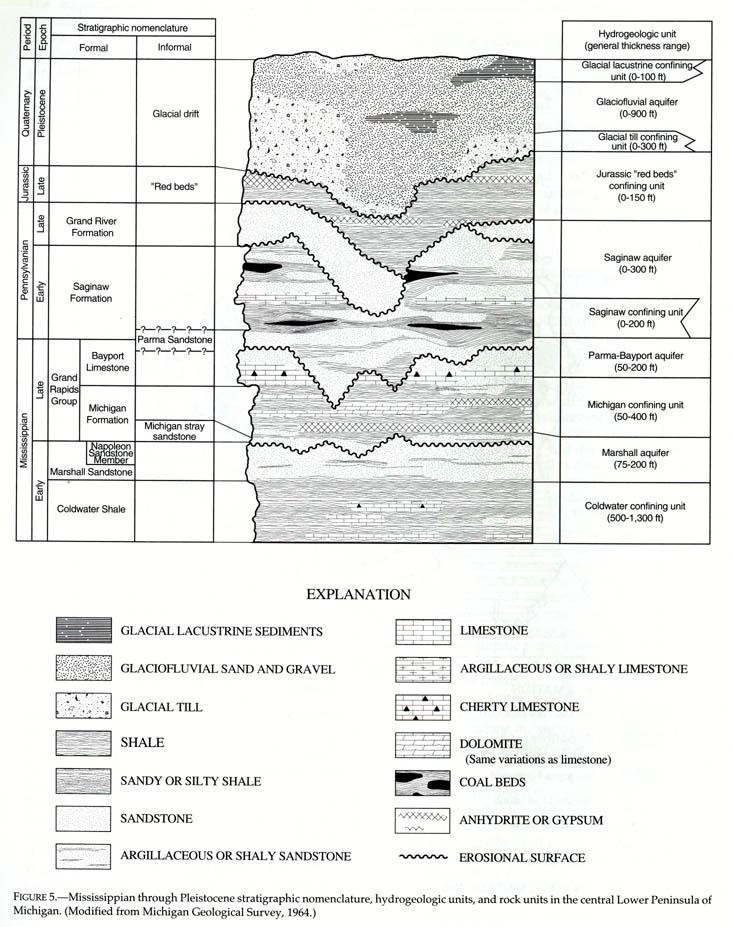

vegetation. Gradually the time changed to the Mississippian --- the first part of the

Carboniferous Period, or the Coal Age. For 35 million years the Mississippian sea

alternately entered and partially retreated from the bay which covered most of the

Southern Peninsula. Note that now the water in the Michigan basin is better described as a

bay, not a sea–it is shallower and warmer. The condition of the lands about our

"Michigan bay" varied so that a variety of sediments were deposited; nor were

the sediments the same in all parts of the basin: we have incomplete bowls. Thick shales

--- black Antrim, green Ellsworth, blue Coldwater --- underlie the Marshall sandstone,

which in turn is overlain by the Michigan shales, sandstones, limestones, and the thick

gypsum beds which indicate an arid climate and chemical precipitation. Near the end of

Mississippian time the Bayport limestone sediments were deposited. Thus, the Mississippian

is characterized by varying depositional environments, but all were shallow-water

sediments of mud and sand. The stratigraphic column below should make all these rock

strata more clear in your mind.

Source: C.M. Davis, Readings in the Geography

of Michigan (1964).

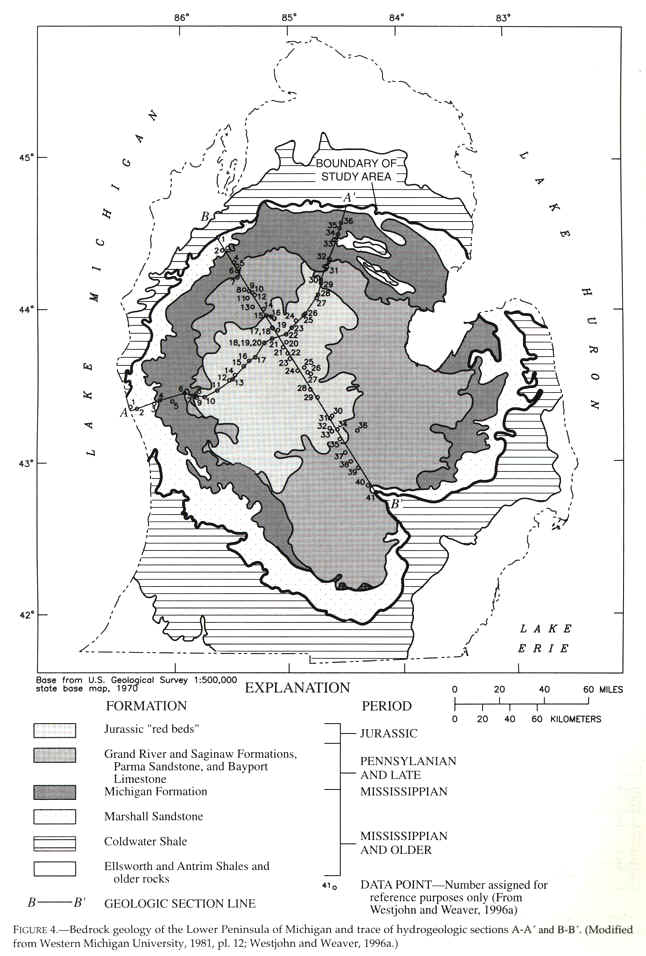

Water within the Marshall sandstone is fresh at the edges of the Michigan Basin, and here

the rock unit is a very good freshwater aquifer. The rim of the Marshall sandstone

comes to, or is near, the surface in many places from the tip of the Thumb where it is

carved to interesting scenery, through Huron, Jackson, Calhoun, and Ottawa counties. In

the early day many quarries were opened in it and the sandstone used for building

purposes. One of our ghost towns is

Grindstone City, Huron

County, where once a flourishing industry produced the largest and finest grindstones, scythestones, and honestones in the world. Artificial carborundum, however, killed that

industry. But when particularly fine grind-and hone-stones were needed the quarry was

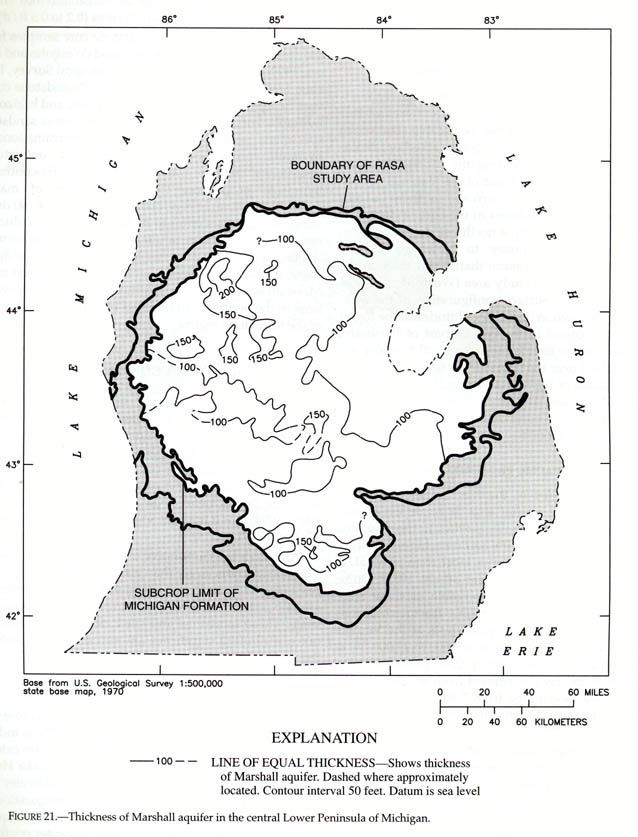

occasionally operated. The map below shows where the Marshall sandstone is the

uppermost bedrock unit.

Source: C.M. Davis, Readings in the Geography

of Michigan (1964).

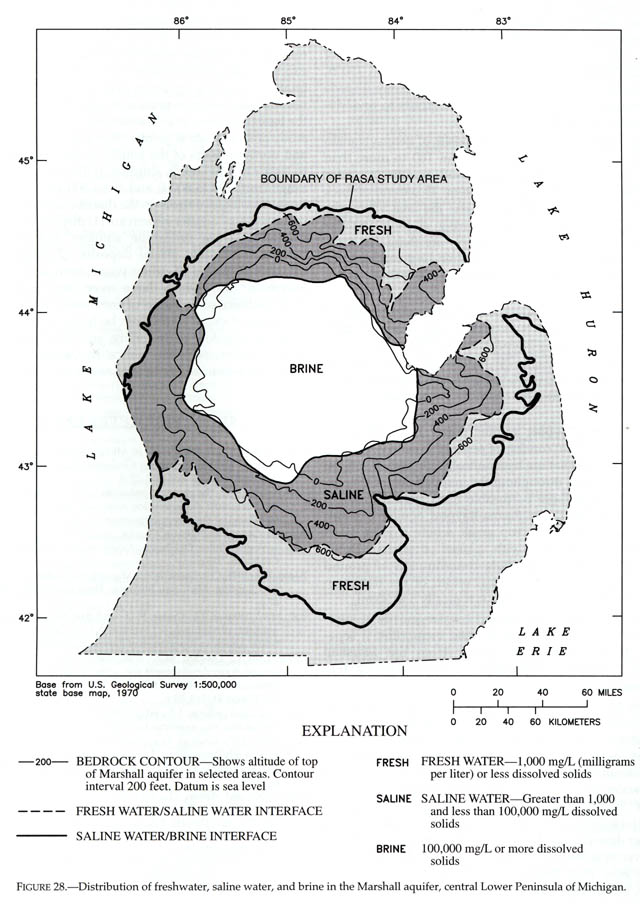

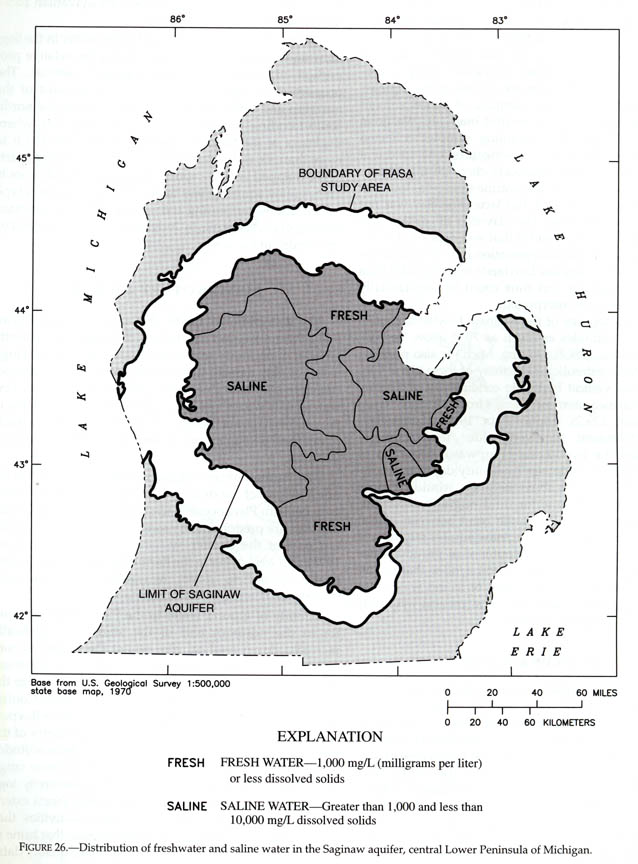

In the center of the basin, however, the sandstone contains very saline

water--6 times as salty as the ocean! The map below illustrates this point.

Source: C.M. Davis, Readings in the Geography

of Michigan (1964).

Source: C.M. Davis, Readings in the Geography of Michigan (1964).

Similar to the Marshall sandstone, and above it, is the Saginaw Formation. It,

too, is a valuable freshwater aquifer that becomes quite saline in the

center of the basin (below).

Source: C.M. Davis, Readings in the Geography

of Michigan (1964).

In most places, the Saginaw is 100-200 feet thick (see below).

Source: C.M. Davis, Readings in the Geography

of Michigan (1964).

Some of the Pennsylvanian sandstones have been used for building

purposes-quarries were operated near Flushing, Corunna, Jackson, and Ionia.

Parts of the text above have been paraphrased from C.M. Davis’ Readings in the Geography of Michigan (1964).

This material has been compiled for educational use only, and may not be reproduced without permission. One copy may be printed for personal use. Please contact Randall Schaetzl (soils@msu.edu) for more information or permissions.