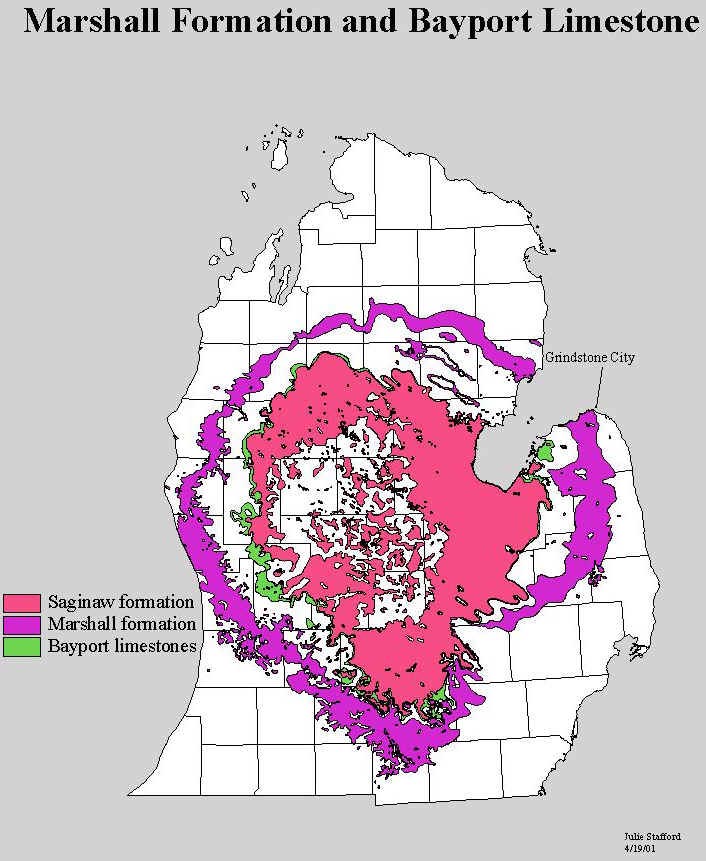

The rim of the Marshall

sandstone comes to, or is near, the surface in many places from the tip of the Thumb

where it is carved to interesting scenery, through Huron, Jackson, Calhoun, and Ottawa

counties. In the early day many quarries were opened in it and the Marshall Sandstone used

for building purposes. One of our ghost towns is Grindstone City, Huron County, where once

a flourishing industry produced the largest and finest grindstones, scythestones, and

honestones in the world. Artificial carborundum, however, killed that industry. But when

particularly fine grind-and hone-stones were needed the quarry was occasionally

operated.

Source: Michigan State University, Department of Geography

An abbreviated history of Grindstone City

An article written by Dorothy Mitts, in the Port Huron Times Herald, states that

most Michigan natives are aware of the importance of Grindstone City’s Historic past

and its importance in the grindstone industry. Its name is synonymous with the finest of

abrasive stone, which was found at no other place in the United States.

In the year 1834, Capt. Aaron G. Peer, with his Schooner, the Rip Van Winkle, was forced

to take haven in this natural harbor, during a storm. Capt. Peer is known as the

"father" of Grindstone City, and located the first land in what is now Huron

County. The sloop took anchorage here in a storm, and that Capt. Peer, his crew and his

father came ashore to what was then a wilderness of pine, cedar, ash, beech, and maple,

the cedar being so thick that snow remained in places although it was midsummer. In

their exploring they found some big flat stone along the beach and on further examination,

found evidence that these strata of rock was underlying the area to a lesser or greater

extent. Samples were taken to Detroit where they were found superior to the Ohio flagstone

which city officials were planning to use to pave some of the streets. He later took some

of this rock to Detroit, where it was used to pave a few blocks on Jefferson and Woodward

Avenues. This was the first use made of grindstone rock as far as is known. It is

interesting to note that the foundations and basements of early brick buildings in Port

Huron; including the Harder and the old Johnston-Howard block later known as the Hartstuff

Block and which now houses the Barnet Drug Store, were built of these stones.

On one trip, the sailors rigged up in a crude fashion a stone

slab and used it to sharpen their tools. That year (1838) Capt. Peer, getting the idea

from the sailors began shaping the grindstones at the place later known as Grindstone

City. The industry was carried on here for a century by Capt. Peer and several other

people and companies. Capt. Peer later bought 400 acres of land, on which to

produce grindstones. It was operated by Jacob Peer, Capt. Peer’s father. Later Pierce

and Smith took over the quarries, and "turned stone" for ten years, until Pierce

died and his share reverted to Capt. Peer. They then built the first mill run by water

power. Previously the turning had been done by horsepower. In 1888, The Cleveland

Stone Company purchased all the properties and quarries around Grindstone City and became

sole proprietors of the industry. They were the last company to own and operate the

quarries and company store.

They had a mill to make whet stones and scythe stones. The stones

made here varied in size and weight from small kitchen stones weighing from 2 � to 10

lbs. and from 6 to 10 inches in diameter; to the huge grinding stones that weighed over

two tons. The largest stone ever turned weighed over 6600 lbs. The memorial stone on the

corner of Copeland and Rouse Road, in Grindstone City, is said to weigh 4750 lbs.

Grindstone City received its name in 1870. It happened in this way. Mr. James Wallace,

one of the owners of the quarry at that time was talking to Mrs. Sam Kinch Sr., when she

remarked that the village was growing so fast that it ought to have a name. They were

discussing Stonington as a name when Mrs. Kinch suggested Grindstone and Mr. Wallace added

City and from then on the village has been known as Grindstone City.

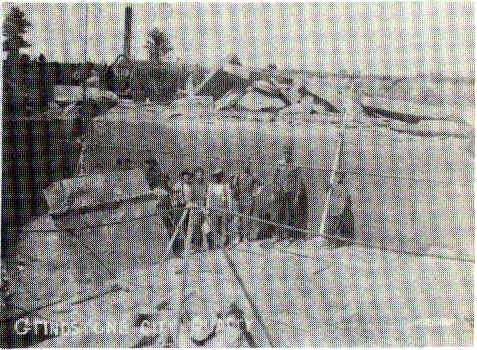

Quarrying the stones

The first step in quarrying the stone was stripping the field to be worked. This was done

by removing all the brush, top soil and shale rock near the top of the ground. The shaling

of rock is caused by water freezing and thawing. This was started in the Fall but finished

in the Spring, at which time the actual work got under way. There were two grades of

rock, light and heavy, the light rock was found from 10 to 15 feet deep and the heavy rock

from 5 to 10 feet deeper. The rock lies in strata or layers, these varying in thickness

from a few inches to a foot or more. The stone was cut with a steam or gasoline operated

drill into square blocks of approximately the size wanted. Then the blocks were loosened

by picks, bars, wedges, etc., after which a hoist lifted them to the top of the ground.

The heavy rock was cut in the same manner, but often had to be loosened by charges of

dynamite strategically placed so as not to damage the stone.

"Grindstone" is a special rock formation from the

Marshall Sandstone. It is a grit stone finer than sandstone and used exclusively as a

sharpening stone, which produces a finer edge than carborundum which has replaced it.

There were two grades of this stone, one called light because it was nearer the top

of the ground and softer. The second grade was called heavy stone and was found several

feet under the ground. Besides being heavier it was finer, thought to be due to the

pressure from the upper layers.

The first step in quarrying this stone had to be done from the

top of the ground. Men would stake out an area thought to be large enough to produce all

the stone they could make in one season. To clear the area all trees, shrubs and soil must

be removed. After removing trees and shrubs, the soil was removed by horse-drawn scrapers.

Following this, all shale had to be removed to get to the usable sandstone. Stone picks

were used to loosen the shale. The stone is in layers and freezing and thawing

causes it to split in layers in frozen areas. Usually the men started to clear the area in

March or April depending upon the weather. The real quarrying was not done until all frost

was out of the ground. The whole system of quarrying in this area was done by hand

tools and manual labor, except for steam engines, derricks and horse-drawn vehicles, as

there was no electricity in the area at that time.

The industry lasted for early 100 years.

After the area called a field was cleared for the actual getting

out of stone the men had to get down to the layers of rock. This was done by drilling

holes and dynamiting to get to the rock where they could start to actually take out stone.

When they had a hole large enough they drilled into the rock from the sides. This was done

by controlled dynamiting and would split the layers of rock apart. Then by a gin pole

arrangement the stone was raised to the top of the ground. Steam drills were used to cut

the stone in squares. After the stone was cut, bars and wedges were used to pry them loose

and they were wedged apart so the gin pole affair could be fastened to them. A gin pole

was made by fastening two poles together, one in the ground and the other fastened to the

bottom by a hinge arrangement. These had two pulleys and a long cable fastened to them.

One end was fastened to the engine and the other had clamps which were attached to the cut

stone. The steam engine operator pulled the stone to the top of the ground by a device

that would the cable around a pulley on the engine. When the two poles were parallel the

stone would be on the top of the ground. It was swung away from the hole and laid flat on

the ground, where men with picks trimmed off the corners and then picked a square hole in

the center. Then the men put the grappling hooks on the stone and the engine

operator lifted it on to a flat car. The grindstone company built and operated its own

narrow gauge railroad truck and cars and engine for this purpose.

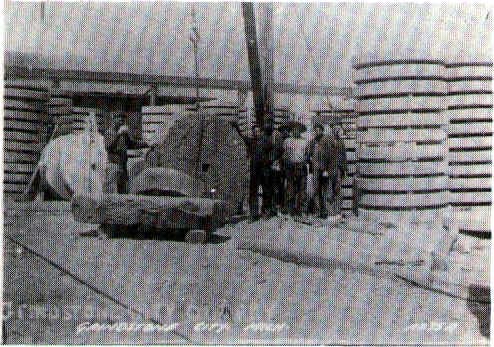

"Turning" the stone

"Turning" a stone means to carve the rock into a flat, round grindstone.

To do this, the stone was first hauled to the mill where it would be finished. Here

another steam engine was used to pick up the stone and it was guided by men to a machine

called a mandrill, where it was put on a large iron bar and securely fastened there by

bolts and washers. However due to the hole in the stone ropes instead of cables were used

in this operation. Men stood on each side of this stone, which was upright on the bar.

With long iron tools held against the stone, they cut the sides and edges of the stone.

These tools were kept sharpened by the blacksmith who worked in a small building close to

the mill. These tools looked similar to our crowbars. The stone was kept turning by

means of a steam engine and pulleys, and the men held their tools against the side of the

stone as it turned, thus cutting and shaping it. When they had done one section they moved

the tool forward to the next spike etc., until they had turned it to the center. The stone

had to be exact for perfect balance or they would not be saleable. When a stone was

finished, it had to be carefully removed from the mandrill so as not to chip the edge,

which would ruin the stone. Stones were soaked to soften them before turning, as the stone

is porous and does chip easily when not wet. The finished stones were piled with

wedges or pieces of lumber between them to allow them to dry. Companies purchasing the

stone wanted it dry as it would be much lighter and they purchased it by the pound. Stone

sold for abut 3 to 3 � cents a pound. Smaller farm stones usually had a flat price

as did both whet stones and scythe stones. They were made in a separate small

factory. Mitchell G. Cook was at one time manager of this operation. Its output was about

140 gross a day.

To regress – The quarry had to be kept clear of rubble, so all the broken pieces of

stone were loaded on two-wheeled horse-drawn carts and dumped into piles or often into a

worked out quarry hole.

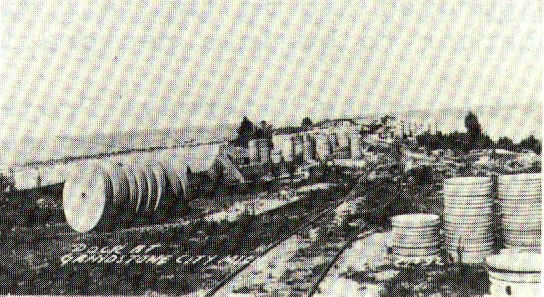

After the stone was ready for market, it was often moved out on a long dock , which still

stands; and piled there to await transportation. Here again they maintained their own

railroad. When they received an order for stone, they would put the stone on the flat cars

and move it to the end of the dock where it was loaded on scows. The scows carried it out

into the lake where steamers awaited and it was loaded on to the steamer to be carried to

its destination. There are two buildings in this town built almost entirely of this rock.

Grindstones from Grindstone City, Michigan found a ready market in Canada, Germany,

Russia, Africa, here in the United States, and many other places throughout the world.

Since 1929....

Due to carborundum taking the place of grindstone after the First World War, the industry

was discontinued about 1929. According to some, this is just one more example of science

and technology killing an industry and a town. Such is progress. All of the good machinery

was shipped from here to Cleveland, Ohio, or sold at private sale. The worn out machinery

was cut up by a steel cutter and shipped to Detroit where it was used for scrap iron.

At the corner of Copeland and Rouse Roads, in Grindstone City, is a huge grindstone

(see below) donated to the town by the Cleveland Stone Co., in honor of the pioneers who

spent their lives working at the grindstone industry here. Mr. Steve Kreinke picked and

shaped the base stone on which the large stone rests. It was dedicated to The Pioneers of

Grindstone City by Dr Wm. Lyon Phelps of Yale University on Sept. 3rd, 1935.

Dr. Phelps was the head of the Literature Dept. at Yale and had a summer home "The

Seven Gables" at Huron City. This stone said to weigh 4750 lbs. stands as a fitting

tribute to a very important industry that was once famous as the only place in the United

States where this particular stone is found.

The text on this page was edited from Mabel Cook's "History of

Grindstone City New River and Eagle Bay" (1977).

This material has been compiled for educational use only, and may not be reproduced without permission. One copy may be printed for personal use. Please contact Randall Schaetzl (soils@msu.edu) for more information or permissions.