When you drive on an icy road, eat a potato chip or wear a

pair of leather shoes, you may be using one of Michigan’s least known natural

resources---salt. During the Paleozoic Era, beginning about 600 million years ago and

ending about 230 million years ago, seawater invaded the Michigan Basin at least six

times. As the seas receded and evaporated, rock and mineral deposits such as halite (rock

salt), gypsum (calcium sulfate with water), liquid brines, petroleum, lime, clay,

sandstone and coal were left behind.

Source: Unknown

During the early decades of the 20th century, Michigan led the nation

in salt production. Michigan is a leading producer of many natural salines---underground

waters rich in chlorides, calcium, magnesium, sodium and, in lesser amounts, potassium,

bromine and iodine. Salt under Michigan has created fortunes, towns and manufacturing

centers. Michigan ranks first in the United States in the production

of calcium chloride (salt) and in gypsum, fourth in cement and sand and gravel, and is a

large producer of crushed stone for a variety of purposes. These minerals are found in the

sedimentary rocks of the Michigan Basin or in the extensive glacial deposits. Salt is

obtained from beds of rock salt (the Salina Formation is but one) over 1,100 ft below the

surface in Detroit and from natural and artificial brines of dissolved salt that are

pumped to the surface in Midland, Manistee, Muskegon, Wayne, and St. Clair Counties. The

salt layers were laid down as evaporite deposits in the seas of the middle Paleozoic

era---in the Mississippian, Devonian, and Silurian periods.

Long before settlers entered Michigan Territory, wild animals

discovered numerous salt springs and used them as natural salt licks (see the map below).

Discoveries of musk oxen and mastodon bones in Michigan are often related to these

salt seeps.

Source: Unknown

Indians took salt from the same springs and sometimes used it as an item of trade with

neighboring tribes. Some of the earliest white settlements were begun at brine springs in

the southeastern part of the state. (Brine is water saturated with common salt.)

Salt was so important to early pioneers that during the winter of

1836-37 in Branch County a 20-pound venison ham could be traded for a fist-sized lump of

salt. Used mainly as a preservative, salt was essential for survival on the Michigan

frontier. Though Michigan possessed an abundance of salt springs, they were not

commercially developed in the 1830s, and Michigan residents spent $300,000 annually on

imported salt. Salt was so important that those in favor of internal improvements in the

late 1830s used it as an example of an eastern commodity made more readily available by

the building of Michigan’s first railroad line.

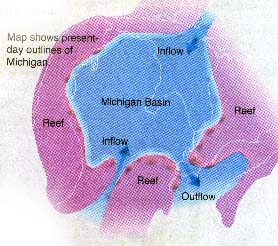

Evaporite deposits (gypsum and rock salt,

or halite) formed in the Michigan basin when waters flowed into the basin, and then

evaporated, depositing the salts. This is referred to as the "Salt Cycle".

Source: Detroit Free Press

ROCK SALT

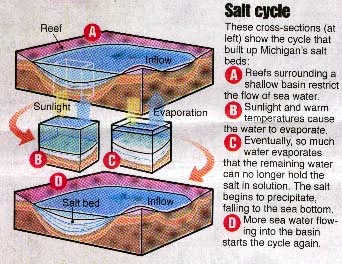

The rock salt of the Michigan basin is one of the major sources of salt in North

America. The map below shows where "table salt" or NaCl, is found (pattern

of larger dots). Note that the salts are found within the center of the Michigan

Basin, which was surrounded by higher, reef deposits.

The map below shows the North American Silurian reef system. The dots represent some of the major Silurian reefs. During the mid-Silurian, large pinnacle reefs surrounded the edges of the Michigan basin. Such reefs are often referred to as "bioherms". Each reef extended up, vertically, from the sea floor, some 200+ meters. They commonly are up to a km in width. Today, these reefs are important oil and gas "traps", and because the limestone in them is so hard and pure, the reefs themselves (when close to the surface) are important sources of limestone. The large quarry on the south side of Chicago, the Thornton Quarry, is crossed by I-94; perhaps you have driven across it!

Source: Unknown

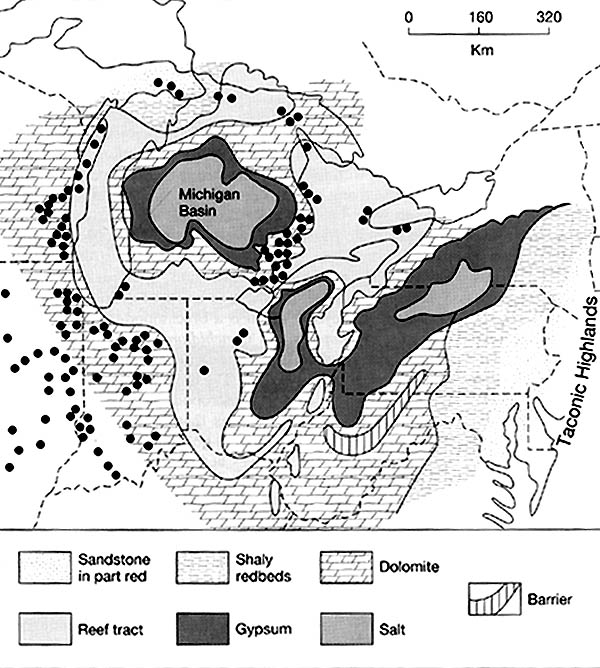

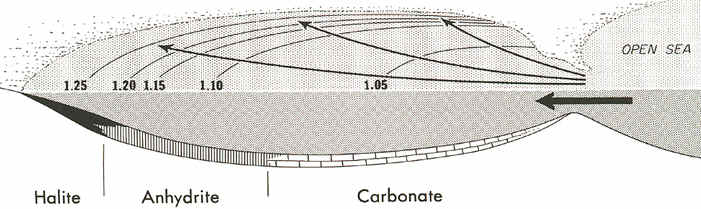

While these reefs were forming, limestone and dolomite were precipitating in the deep

waters of the basin, but near the "inlets" to the basin. In the farthest

and cleanest parts of the basin, however, halite salts and gypsum salts (anhydrite) were

precipitating out in sedimentary beds (see below).

Source: Unknown

The image below shows salt beds exposed in a Michigan salt mine. The red markings are

spray paint, put on the walls to identify the location in the mine. From the top to

the base of the image is about a meter. Note that the salt occurs in distinct beds,

or layers. This layering is due to the fact that the salt was deposited

layer-by-layer in an evaporation basin. The darker layers are still salt, but

contain some admixtures of silt and clay (i.e., the water was muddier then).

Source: Photograph by Randy Schaetzl, Professor of Geography - Michigan State University

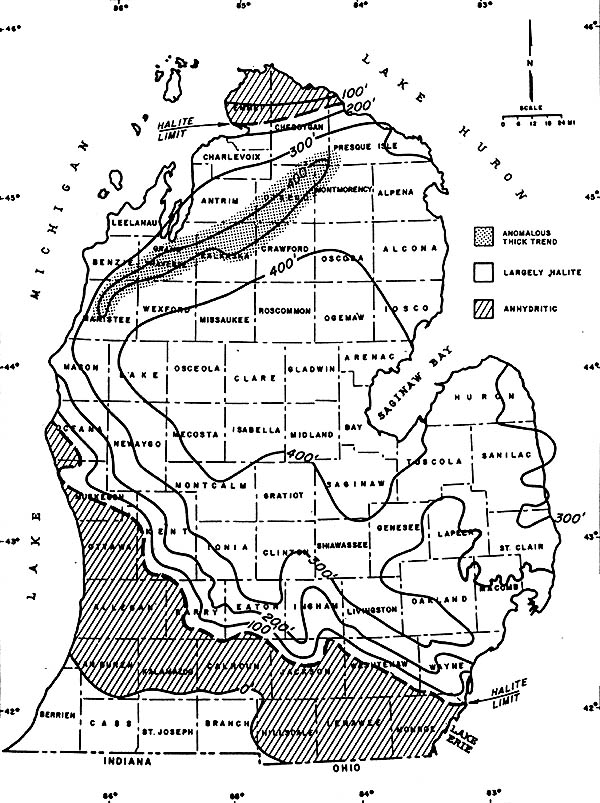

The map below shows the thickness of one of the salt deposits, the Salina Salt, in

southern Michigan. The salt is thickest (over 400 feet thick!) where the basin was,

presumably, deepest. One notable exception to this trend exists in NW Lower Michigan,

where a 400+ foot thick layer extends to the SE of the barrier reefs that also exist

there. Note also that this salt is predominantly halite in the center of the basin,

and has more anhydritic (gypsum-like) characteristics at its edges.

THICKNESS OF THE SALINA SALT IN THE MICHIGAN BASIN

Source: Unknown

From the Salina (late Silurian) salt beds we are assured of a salt supply

of some trillion tons. Beds of pure rock salt 400 to 1600 feet thick, with additional

thinner beds alternating with shales, dolomites, and gypsum, underlie the Southern

Peninsula. At Port Huron, St. Clair, and Detroit, hot water is pumped into the salt to

form artificial brines which are then pumped up and used in the manufacture of salt and in

the chemical industries. The last active salt mine in Michigan (now closed) was 1100 feet

under Detroit in the clear Salina rock salt. One of the largest gas wells in the State is

obtaining gas from the Salina formation; thus it is a potential producer of gas in other

parts of the Michigan basin which it underlies.

The rock salt is used for packing meat and fish, for the manufacture of

soda ash, caustic soda, bleach, and other chemical preparations, refrigeration, and

agricultural purposes. Salt

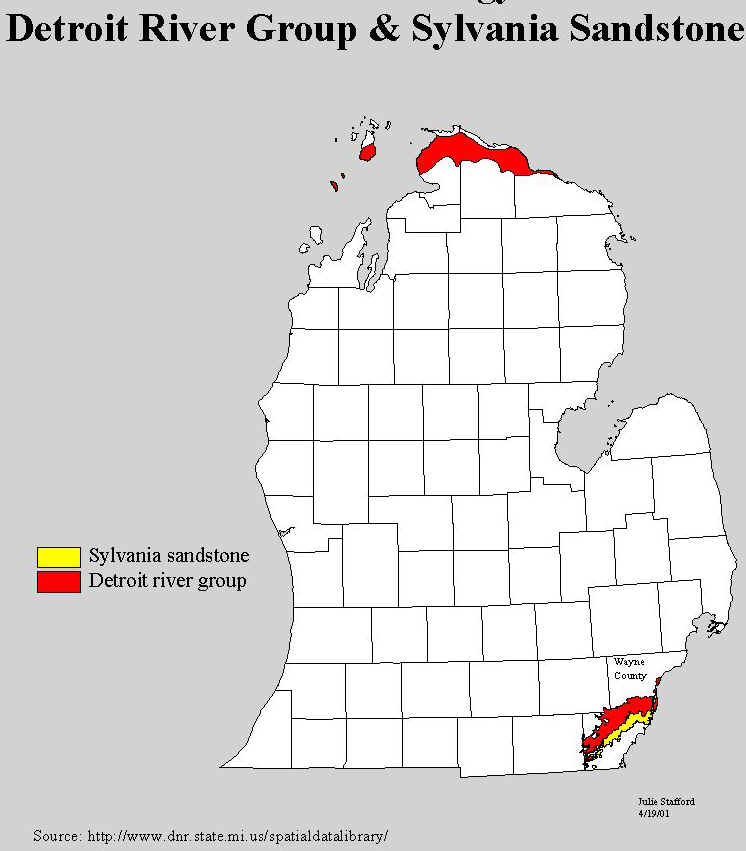

brine is also pumped from the overlying Devonian rocks. The deeply buried Devonian

rocks (above the Sylvania) have made mineral contributions that are the most recent and

most spectacular. For many years salt brines have been obtained from the lowest of these

rocks (the Detroit River formation, see map below for the location of the outcrops of the

Detroit River Group rocks) to supply the salt industry in Manistee and Ludington.

Source: Michigan State University Department of Geography

Some of the images and text on this page were taken from various issues of Michigan History magazine and from C.M. Davis’ Readings in the Geography of Michigan (1964).

This material has been compiled for educational use only, and may not be reproduced without permission. One copy may be printed for personal use. Please contact Randall Schaetzl (soils@msu.edu) for more information or permissions.