There were two phases in the lumbering operations in Michigan. In the first of these, river logging, the timber was floated down the streams to the mills. The area which could be tapped by this method was limited to that within easy reach of the main rivers and their principal tributaries. In the second phase the railroads replaced the river as the main carriers, and, since logging branches could be constructed almost everywhere, this effectively cleaned up the rest of the merchant timber.

River logging was primarily a winter business. Only when the swampy ground had frozen over and ice covered the roads could logs be handled with minimum expense. The crew went into the woods in September and established a camp at a spot convenient to the area marked for logging. From that time until the beginning of winter the primary job was the construction of roads.

These roads had to be not less than 25 feet wide, without steep grades and free from all obstructions. Streams were bridged and swamps spanned by roads of logs called "corduroys". The easiest grades (i.e., slopes) were along the creek bottoms where, unfortunately, soft ground, piles of windfalls, vines, and bushes made road building most difficult. On the uplands the roads wound through the timber following the easiest grades and penetrating all parts of the district to be logged. At intervals along the road small square clearings were cut where the log piles would be established. When the actual cutting had started, narrow trails were made back from the roads through the timber. These were the "travoy" (travois) roads, or skid trails over which the cut logs were "snaked" out to the skidways.

In order to

process the timber, most cut logs had to be transported to rivers, and then down those

rivers to sawmills. There were rare occasions when there

was not enough water to float the logs, and in those years pine logs left in the woods

would rot or be destroyed by fire.

The early sawmills and lumbering centers were, therefore, mainly

situated at the mouths of rivers, which made harvesting the nearby timber a relatively

easy and efficient task. Communities such as Muskegon (1837), Traverse City (1850), and

Menominee (1865) owe their existence to the logging boom. As the coastal supplies were

depleted, cutting operations moved upstream and inland, and interior mill towns like

Cadillac, Roscommon, and Grayling were founded.

Source: Unknown

Before logs entered the river, there was preparation work. An efficient drive required the

waterway channels to be cleared of rocks and trees that might catch logs and create a

dreaded jam. Often dams were built in the headwaters to control the flood stages, so that

a series of artificial freshets might be available to carry logs, rather than one big

natural flood that might leave some of the valuable timber behind to wait for the next

year’s flood.

The second of the logging operations which has left its traces upon the

landscape was the clearing of the streams for the "drive" when, upon the high

water of spring, the logs would be floated down to the mills. The debris of centuries of

floodwater choked the streams; old snags and stumps lay imbedded in the ooze; decayed

trunks, moss-grown, blocked the current and all of this had to be removed. In some places

the carrying capacity (i.e., flow) of the stream was increased by a series of dams. Along

the stream banks were constructed very large skidways called "rollways"

on which the logs were piled ready to roll into the stream when the drive began.

Rollways were dangerous places--when the logs came toppling down, many a man lost a limb

or even his life.

Source: Unknown

Sometimes the lumberjacks built log slides, like the one shown below, to facilitate the

transport of logs from the uplands to the river.

Source: Unknown

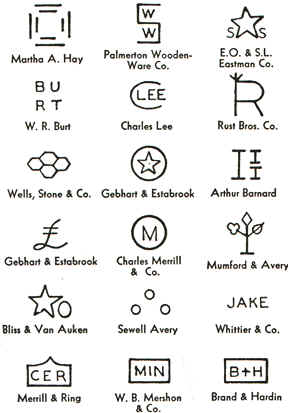

Before the logs were to be sent downstream, however, each had to be

identified by owner. To do this, log marks, each one different for each different

logging company, were affixed to the ends of the logs (similar to the cattle brands used

in the West). The design of a log mark might include the initials of the lumber company's

owner or symbols from the logging industry or from nature. The designs were cast into the

metal end of a marking hammer by a blacksmith. The symbols needed to be simple, clean

designs so the person who struck the log with the marking hammer could cut the design

easily into each log. According to an 1842 Michigan law, the marks had to be

registered in the county of the logs' destination (usually the location of the sawmill).

These are some Michigan log marks with the name of the person who registered each and the

year and county of registration: Examples of such marks are shown below.

Source: Unknown

Source: Unknown

Source: Unknown

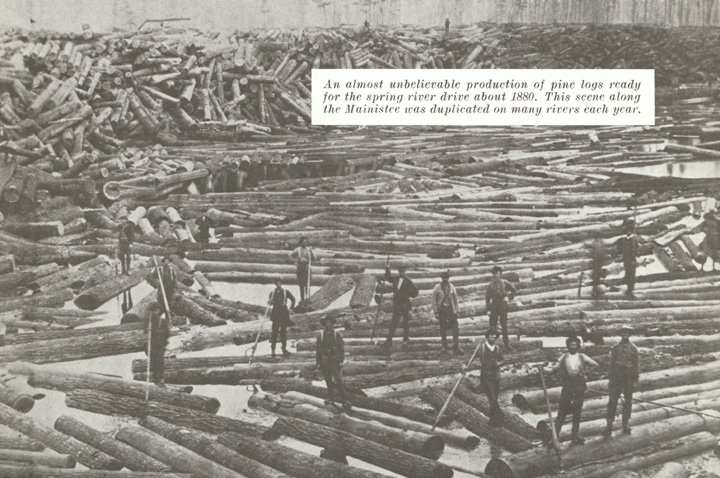

Once marked, chutes or rollways such as the one below on the Manistee River, were used to get the logs to the water. Logs would be piled up at the top of the chute all winter long, and then when the spring floods came, the logs would be chuted/rolled down into the river. Where chutes did not exist, the logs would simply be piled up neatly on a high bank (below), and then at an appropriate time, the bottom logs would be pulled out and the entire pile would go rolling down to the river.

The log drive was the most exciting and picturesque of the logging

operations. The logs went down the stream, in many cases for a hundred miles of more, but

not always smoothly or easily. A few logs would catch on an obstruction or on one another;

more would follow in, and soon a log "jam" was formed.

In some places this could be blasted loose, in others, the courageous lumber jacks would

pick out the "key logs" until the whole thing gave way. The men followed along

with the drive keeping the timber moving and riding on the logs. There was much to do; the

logs would drift out of the current and become stranded, dams and sluices had to be

passed; jams formed and were broken. The work lasted from dawn until dark. At the rear of

the drive came the cook's clumsy flatboat.

As you can imagine, dry weather (especially low-snow winters) had

potentially devastating affects on river and lake levels. During the lumbering era these

issues developed into "traffic" problems. The biggest headache for moving logs

down river was low water levels. Delays that played most havoc with log transport were

those due to lack of water for flotage. When it was dry and water was down, great

difficulties were experienced in driving logs downstream. This caused many mills to sit

idle, and some lumber companies to go out of business.

Finally, however, the logs floated into the quiet water of the mill

booms, the men were paid off and another drive started -- this time toward the saloons.

Source: Unknown

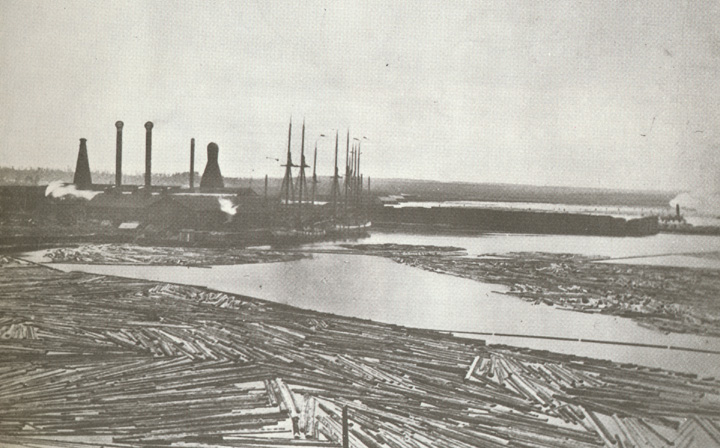

The end point of all this effort was the sawmill, typically

located at the mouth of the river, on the Great Lakes.

Source: Unknown

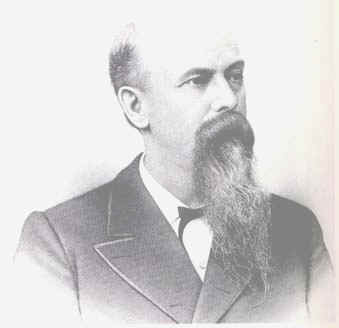

One of the more famous of the many "lumber barons" in Michigan was Charles

Hackley, of Muskegon (below). Although he amassed great wealth via his lumbering

operations, much of this money he gave back to the city of Muskegon for schools,

hospitals, and the like.

Source: Unknown

Source: Unknown

Hackley's mansion in Muskegon.

This material has been compiled for educational use only, and may not be reproduced without permission. One copy may be printed for personal use. Please contact Randall Schaetzl (soils@msu.edu) for more information or permissions.