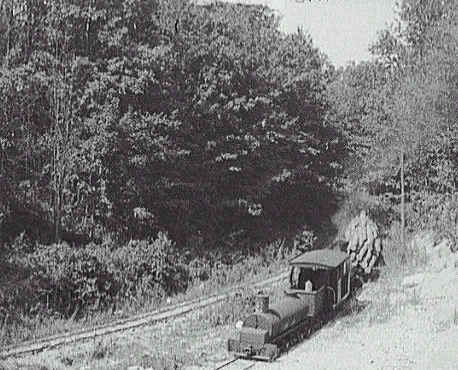

From 1870 to 1890, Michigan was the nation’s leading timber producer, and its sawmills were among the most efficient in the world. Logging had become a large-scale industry that utilized the latest technologies like steam-powered sawmills and circular saws. The spread of the railroad, accelerated by the development of narrow-gauge moveable track, made the more remote forest areas accessible. Production peaked in 1888 at 4,292,000,000 board feet. As technology improved, the wood in Michigan was more quickly taken, especially with the introduction of the logging railroad in the 1850’s. These small engines and their portable narrow gauge track made it possible to log farther away from the rivers. These railroads could haul loads of logs no matter the weather. Other improvements included the use of the crosscut saw to fell the trees much more quickly than the axe, the circular saw in the mills and the "big wheel" for logging in the summer months.

Construction of logging railroads became commonplace during the 1880s. By 1887 there were 89 logging railroads in Michigan (Williams 1989). Tracks would be picked up and re-laid through the forest as often as yearly in order to quickly clear out the last substantial trees (Williams 1989). Regions logged in this manner were efficiently stripped of all pine lumber within a short period of time, leaving few or no large pine trees standing. Fire frequently followed logging because the large amounts of dry slash provided ample fuel (Whitney 1987). In dry years, smoke from the constantly burning fires in the Lake States could be so thick that it became a hazard to navigation on Lake Michigan (Fries 1951).

Rusty spikes and broken rails strewn along abandoned railroad grades; splintered and weathered trestle pilings submerged in lakes and streams; rotting ties and ghostlike depressions on former right-of-ways; cuts, fills and Swede holes---all of these archeological remains are mute testimony of a once-vigorous era when enterprising lumbermen used steam locomotives and steel rails to transport their logs to market. More than 500 logging railroads penetrated the vast coniferous and deciduous forests of Michigan’s two peninsulas, bringing out merchantable timber for lumber-hungry customers throughout the Midwest and the Northeast. Although logging railroads lasted slightly more than a century, they completely changed the basic pattern of lumbering from depending on Michigan’s unpredictable weather to using modern technology to meet transportation needs.

Source: Image courtesy Michigan History Magazine

This earliest phase of "river lumbering" was

confined to areas near rivers and streams. It was unprofitable to haul the logs any

considerable distance by teams to the water. Therefore, there remained great stretches of

forests on the interfluves (high areas of land between the river valleys) which

could not be reached by this type of operation, but these also were soon to fall as the

railroads introduced the second phase of lumbering. It was apparent early in the

lumbering business, however, that there were great stands of pine which could be brought

to the mills only by railroads, but until about 1865 the rivers supplied the demand and

the railroads were having financial trouble.

Transportation was a major expense lumbermen encountered when

attempting to convert the wood of a tree into wealth. Horse-drawn sleighs were used to

haul pine logs over snow-covered frozen ground to streams where the logs were banked

(piled up) until these piles were broken and dislodged for the spring log drives in the

raging torrents that were Michigan’s rivers. Michigan’s unpredictable weather,

however, made river-logging a risky business. Frequent

mild winters made sleighing impossible, bankrupting loggers when they could not sleigh

their logs from the skids to the banks of streams. Occasionally, forests were so far from

a stream that lumbermen could not make a profit because of the cost of hauling logs by

sleigh. Lumbermen were forced into selective logging, leaving smaller, yet potentially

profitable, trees standing because sleighing was too costly.

Also, when all available forests near the main rivers were logged, more

"interior" forests were looked to for lumber resources. To get to these logs, big wheels and (more importantly) railroads were built into the

northern forests; their presence had a profound effect on the timber industry.

Source: Image courtesy Michigan History Magazine

In the years immediately following the Civil War there was an increased

demand for lumber in the west and the rivers of the Saginaw district could no longer

supply the capacity of the mills. Thus, railroad logging began in earnest. The first

of the logging railroads, the Pere Marquette, passed through the best of the white pine

lands of the state from Saginaw to Ludington on Lake Michigan. It tapped the pine and

hardwood country of the southern part of the High Plains in Clare, Osceola and Lake

Counties. The second railroad, the Michigan Central, took a more northerly slant into the

center of the High Plains and northward to Mackinac. It passed through Ogemaw, Roscommon,

Crawford and Otsego Counties. A third road, the Grand Rapids and Indiana, ran northward

from Grand Rapids through the western part of the High Plains. The progress of these lines

through the pine lands was marked by a chain of sawmills operating by somewhat different

methods than those of the river lumbering.

The railroad was a dependable substitute for the river. Like

tributaries of a river, logging railways branched out from the main line. These narrow-gauge

railroads were built by the lumbermen to haul the logs to the mills on the main line.

Although the rails have long since been taken up, the old grades of these railroads can be

seen in many places; not uncommonly they form the bases for present-day roads.

Railroad lumbering was an all-year business. In the summer high-wheeled

carts replaced the bob sleds and double sand trails, the iced roads. Logging had lost much

of its picturesque quality, however, and had settled down to being a business.

Logging railroads could be built almost anywhere and permitted

operations to expand rapidly. Within three or four years after the main lines had been

extended, logging was being carried on in almost all parts of the pine country and the

forests which 10-15 years before had "caused the speculative eye of the timber hunter

to dilate with joy, "now sang their swan song to the music of the axe and saw".

Source: Image courtesy Michigan History Magazine

The demand for Michigan’s pine lumber soared when the Illinois and Michigan (I&M)

Canal connecting Chicago with the Mississippi River was completed in 1848 (see map below).

But the mild winters of 1848, 1849 and 1850 prevented lumbermen in the Grand and Muskegon

River valleys from getting logs to their sawmills fast enough to supply Chicago merchants

with lumber for customers living on the prairies.

In 1850 two Grand River valley lumbermen attempted to speed up the

process of moving logs from the skidways to the banking grounds by constructing wooden

railroads and using horses to pull carloads of logs. These two experiments in horse

logging by wooden rails were successful enough that at least three additional logging

railroads were built in the Grand River valley during the next decade.

Trains led to a gradual decline in log driving and rafting on rivers,

and enabled logging to continue year-round. Previously, logging had ceased in the summer

months because of the difficulty of transporting logs overland to navigable streams, and

because some species of trees (those not of the Pinus genus) were of high density

and did not float well on water.

Railroads also permitted deeper penetration into forested areas: spur lines made it

possible to cut all marketable timber. Like the Big Wheels,

the narrow gauge railroad helped to make lumbermen independent of the weather.

The First Successful Railroad "Experiment"

In 1857 the Blendon Lumber Company purchased a seven-year-old Michigan Central locomotive

and began hauling logs on wooden rails. They built their railroad southwest from the Grand

River several miles into the Bass River valley to reach "2500 acres of good pine,

almost in a body, on a part of which there was some good white oak." Old Joe, as the

Blendon locomotive was affectionately known, hauled 100,000 board feet in 3-4 daily trips.

The logs were dumped into the Grand River at Blendon Landing (now the southeast corner of

Grand Valley State University’s campus) and floated down to the Nortonville sawmill

(just upstream from the site of present-day Spring Lake).

Logging railroads made it profitable for lumbermen to clear-cut forests, taking not

only trees containing less merchantable timber, but cutting hardwood stands as well as

white pine. Ash, cherry, hickory, oak, walnut and other hardwood trees were cut and

transported to the Blendon Landing sawmill for conversion into ship timbers and other

hardwood products. Litchfield built a shipyard at Blendon Landing, loaded the hulls of

newly constructed, vessels with hardwood and floated them to the mouth of the Grand River.

Cordwood was also cut for fuel and shipped via scows to Grand Rapids. An estimated

40,000,000 board feet were transported on the Blendon Lumber company railroad before it

ceased operating in the late 1860s.

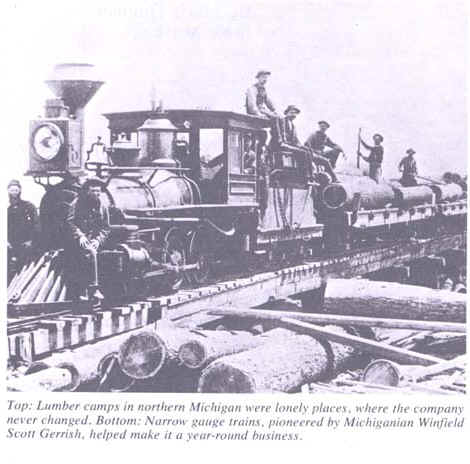

Winfield Scott Gerrish’s logging railroad, which first began

operating in 1877 and connected Clare County’s Lake George with the Muskegon River,

often has been claimed to be Michigan’s first logging railroad. However, more than

fifteen logging railroads were built and operated in Michigan prior to1877, including at

least three that used steam locomotives.

Source: Image courtesy Michigan History Magazine

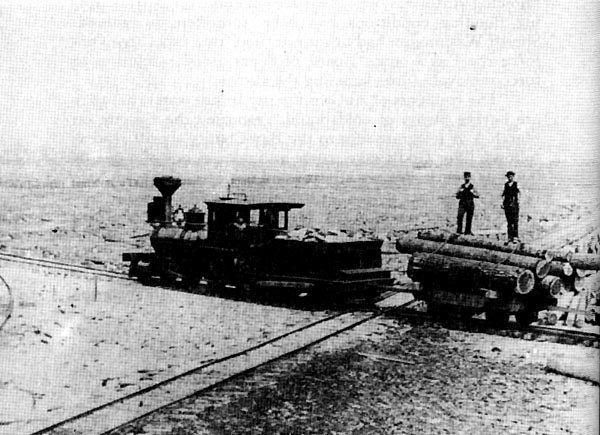

Trains could be used in place of sleds year round for the relatively short run to the

riverside banking grounds, or the river drive itself could be avoided entirely by carrying

the logs to a mainline railroad depot. In addition, the logging railroad was sufficiently

economical to allow cutting in areas that had been considered too far from the nearest

driving stream to make sledding practical.

Source: Image courtesy Michigan History Magazine

Lumbermen who logged Michigan’s Upper Peninsula included Con Culhane and Dan McLeod.

Culhane reportedly moved his logging equipment and railroad south from the Little Two

Hearted River to the Tahquamenon River valley one winter by laying tracks in front of him

as he went across frozen swamps, then picking them up behind him. McLeod built a logging

railroad across one of the Upper Peninsula’s worst cedar swamps without even

bothering to fill in the grade with sand or build trestles. He did anchor the ties to long

stringers and build two bridges where his railroad crossed branches of the Two Hearted

River.

Source: Image courtesy Michigan History Magazine

Michigan lumbermen were not the first to use railroads to carry logs, but the idea of

using temporary narrow gauge track to supplement other means of transportation did

originate within the state.

The image below is typical of a narrow gauge logging railroad--note the narrowness of the

rails.

Source: Image courtesy Michigan History Magazine

Railroads also allowed for logging of the drier, upland sites in the extreme interior of

the state, such as those areas north of Grayling where tremendous stands of pine forest

existed.

Source: Image courtesy Michigan History Magazine

Rail transport became essential as the availability of the prized softwoods declined:

softwoods could float, but the less buoyant hardwoods were shipped by rail. Rail also

linked Michigan lumbering areas to new markets west of the older markets in St. Louis and

Chicago.

Source: Image courtesy Michigan History Magazine

Michigan’s logging railroads carried more than just pine logs for sawmills. Huge

timbers were cut for use in the shipbuilding industry, as well as for the homes of wealthy

European aristocrats. Many Upper Peninsula railroads carried timbers for shaft and tunnel

supports in iron and copper mines. The primary function of several large logging railroads

was to provide charcoal wood to numerous charcoal kilns in both the Lower and Upper

peninsulas. Logs were hauled to chemical manufacturers at Cadillac, Manistique, Marquette

and Newberry. Hemlock bark was hauled for use in tanning. Hardwood was cut to produce

cordwood for fuel and pulpwood for the paper industry. Cedar poles for telephone and

electric power lines and cedar posts for fences moved over the rails. Oak and later cedar

railroad ties were delivered to main-line railroads. Hardwood logs were delivered by the

trainload to numerous Michigan manufacturers such as furniture

factories in Grand Rapids, a basket factory in Holland, a shoe last factory in

Cadillac, a refrigerator factory in Belding, a maple-flooring factory in Hermansville and

an automobile factory in Iron Mountain.

Logging railroads dominated Michigan’s pine-logging and

hardwood-logging eras. Pulpwood loading yards and gondola cars scattered throughout

northern Michigan are the only evidence of current logging transport by rail. Today, the

steam locomotives that ran only where tracks were laid have been replaced by diesel-engine

trucks that travel almost anywhere on their rubber tires.

Railroad lumbering oriented itself upon the pattern of the main railroad lines. The mills were close to the cutting areas instead of at the mouths of the rivers, thus bringing settlements into the timber lands. Although lumbering had been carried on along the rivers for some years before the railroads came in, the towns along these rivers are on the railroads, and ordinarily date from their coming.

The lumber industry helped to shape the state’s industrial landscape. Wood product industries manufactured furniture, sashes, doors, blinds, barrels, wagons, carriages, housewares, caskets, and railroad ties. Wood industries grew rapidly in the 1860s and 1870s, with a large influx of skilled immigrant labor and access to new raw material. The lumber industry also enabled Michigan to become a leader in pulp and paper production. Changes in papermaking technology is the 1870s - away from cloth and straw and toward wood pulp - allowed of a continued demand for logs too small for lumber ("pulp" wood logs).

Some of the images and text on this page were taken from various issues of Michigan History magazine, and parts of the text above have been paraphrased from C.M. Davis’ Readings in the Geography of Michigan (1964).

This material has been compiled for educational use only, and may not be reproduced without permission. One copy may be printed for personal use. Please contact Randall Schaetzl (soils@msu.edu) for more information or permissions.