THE NIAGARA ESCARPMENT

In the long interval between the Jurassic (about 200 million years ago) and today, few

rocks were actually forming in Michigan. Instead, all the forces of erosion were at

work creating much of our scenery, exposing our mineral wealth, and creating some of it.

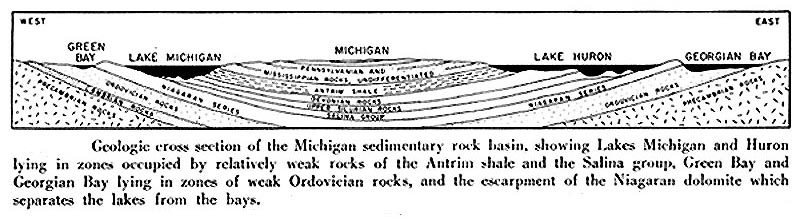

In the Paleozoic area (the Michigan Basin) the edges of the rock layers

("bowls") were leveled off and their rocks exposed. The thin edges the hard

resistant formations were worn away so that the outer edges are now high cliffs or

escarpments. Such a structure --- a short steep slope over the exposed edges of rock

layers, and a long gentle slope in the opposite direction down the top of the strata, is

called a cuesta. The summit of a cuesta may be miles in length. The steep slope of the

Cambrian cuesta borders Lake Superior. In the red and white sandstone of the escarpment

the famous Pictured Rocks, Miner’s Castle, Chapel Rock have been carved. Over the

edge of the Cuesta escarpment streams fall in misty beauty to the lake and the Tahquamenon

drops in majestic grandeur over its ledges from quiet river reaches to rapids below. On

the back of the escarpment, the Cambrian rocks slope gently under the Southern Peninsula.

The Ordovician Trenton limestone stands as an escarpment farther south,

floored on the Cambrian sandstones, but is not so pronounced as another escarpment eight

to twelve miles still farther south --- the edge of the massive Niagara (Silurian)

limestone. The softer rocks between the Trenton limestone and the Niagara dolomite were

eroded into a deep moat between the two resistant formations so that these two rock

formationss stand like ramparts across the peninsula guarding the lands to the south.

Other, soft rock rims were also eroded to troughs, therein forming the curving channels

where we now find Green Bay and Georgian Bays, Lakes Michigan, Huron, Erie, and Ontario.

In these channels, curving around the Michigan Basin, a river system was developed which

carved the basins for four of our Great Lakes. The Devonian limestones were carved into

low cuesta ramparts around the northern edge of the Southern Peninsula from Thunder Bay to

Traverse Bay. But the Devonian strata of the southeastern part of the State are flatter

and were therefore not carved to pronounced escarpments like the Niagara was.

Finally, when the older underlying shales were eroded, the resistant

edges of the Mississippian formations were left as cuestas that almost encircle the

Southern Peninsula.

After Dorr, J.A. Jr. and D.F. Eschman. 1970. Geology of Michigan. Univ. of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor.

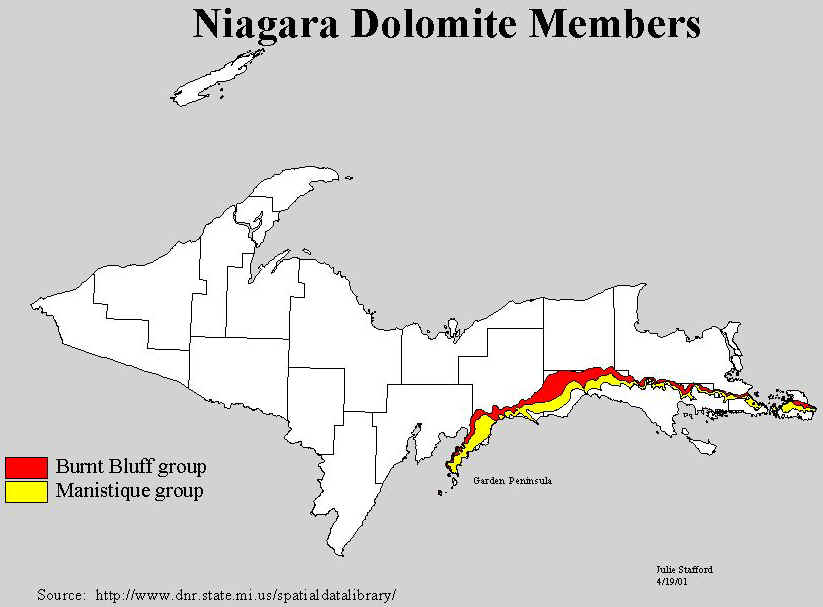

The thick sequence of

Silurian (Niagara) dolomite that surrounds, and dips gently under, the Michigan Basin is

very resistant to erosion. Therefore, it tends to form a prominent topographic feature

(the Niagara cuesta) and it outcrops in many places as high, rocky cliffs.

The eroded edge of these rocks forms an escarpment that can be traced almost continuously

along the eastern part of Wisconsin, the Upper Peninsula of Michigan, and on east to New

York State were Niagara Falls is formed by waters flowing off the Niagara dolomite onto

the softer underlying shales. This escarpment is generally referred to as the Niagara

Escarpment.

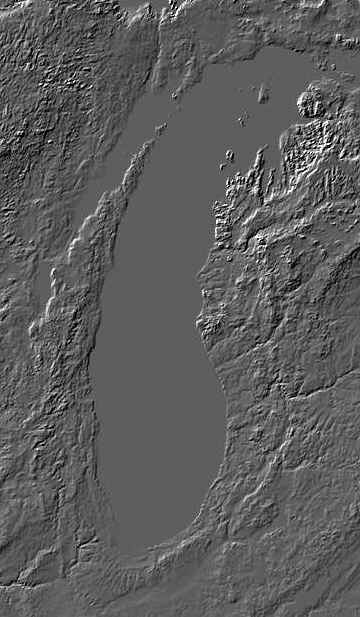

On the image above, the Niagara escarpment is the ridge on the west side of the Door

peninsula (Wisconsin), which continues across to Michigan's Garden peninsula, and then

east across the southern UP.

Note in the geologic map and cross-section below, how the Silurian rocks (primarily the

Niagara dolimite) stand up as resistant layers on the west side of the state, as the Door

and Garden Peninsulas, and the Bruce Peninsula and Manitoulin Island.

This material has been compiled for educational use only, and may not be reproduced without permission. One copy may be printed for personal use. Please contact Randall Schaetzl (soils@msu.edu) for more information or permissions.