The Chippewa Indians, also known as the Ojibway or Ojibwe, lived mainly in Michigan, Wisconsin, Minnesota, North Dakota, and Ontario. They speak a form of the Algonquian language and were closely related to the Ottawa and Potawatomi Indians. The Chippewas were allies of the French and French traders often married Chippewa women. Chippewa warriors fought with the French against the British in the French and Indian War. But political alliances changed with the times. During the American Revolution the Chippewas sided with the British against the Americans.

The Ojibwe (said to mean "Puckered Moccasin People"), also known as the Chippewa,

are a group of Algonquian-speaking bands who amalgamated as a tribe in the 1600's. They

were primarily hunters and fishermen, as the climate of the UP was too cool for farming.

A few bands of Ojibwe lived in southern Michigan, where they subsisted principally

by hunting, though all had summer residences, where they raised min-dor-min (corn),

potatoes, turnips, beans, and sometimes squashes, pumpkins, and melons.

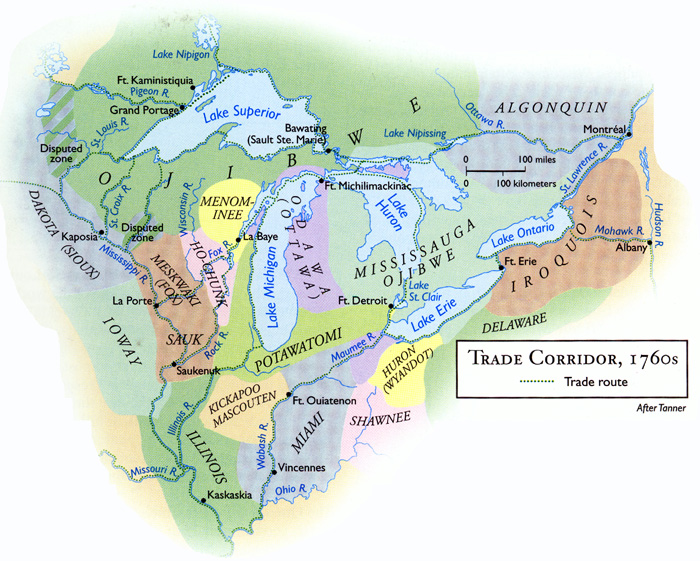

Click here for full size image (220 kb)

Source: Atlas of Wisconsin

By about A.D. 100, Native American inhabitants of the Upper Peninsula (Ojibwes) were

using improved fishing techniques and had adopted the use of ceramics. They gradually

developed a way of life based on seasonal fishing which the Chippewas/Ojibwes still

followed when they met the first European visitors to the area. Scattered fragments of

stone tools and pottery mark the location of some of these prehistoric lakeshore

encampments.

Source: Unknown

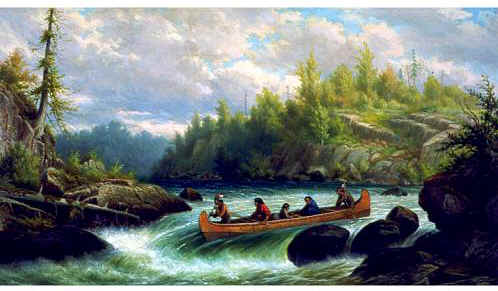

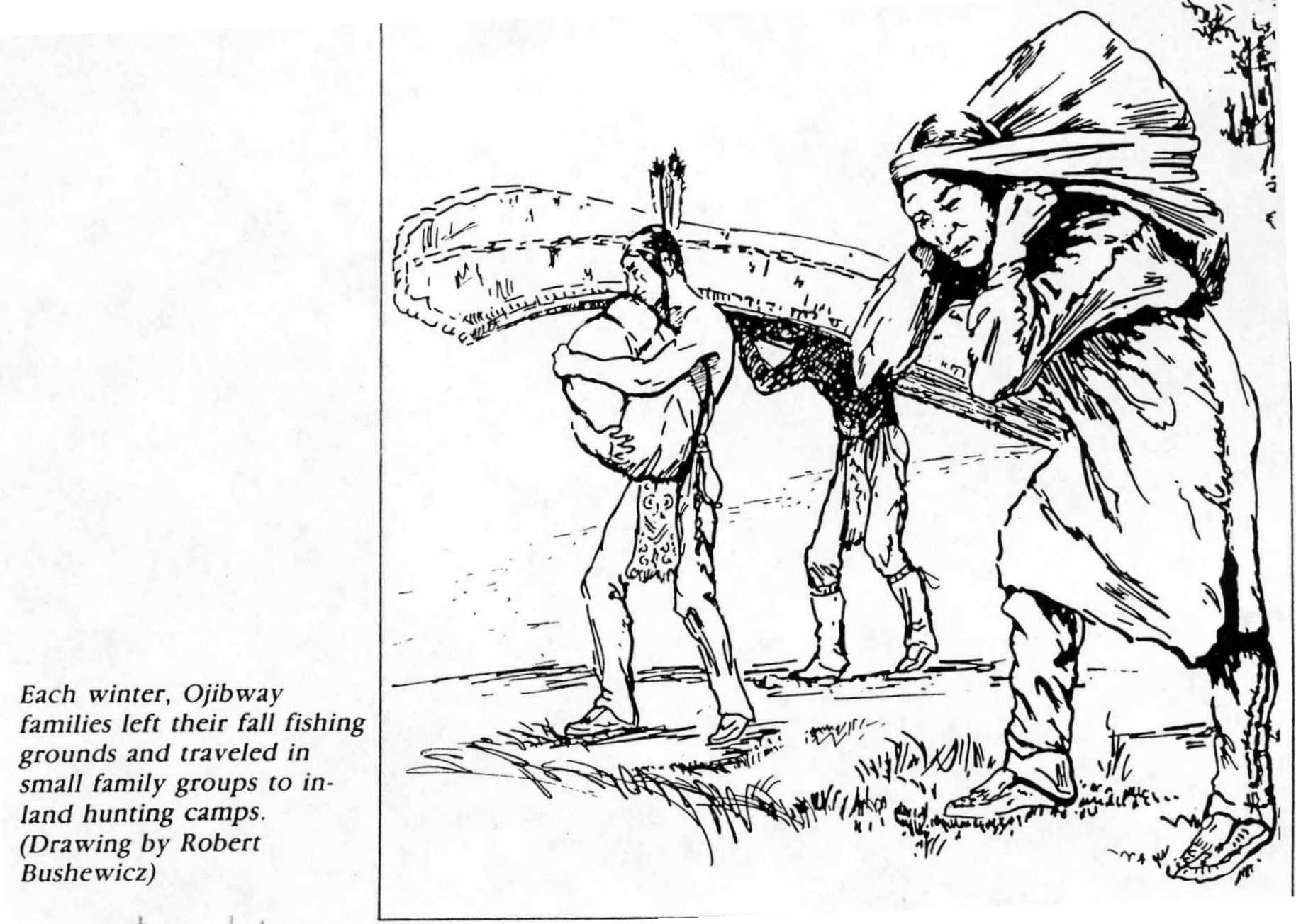

Organized into independent migratory bands, the Ojibwe were ideally

suited to fur trade with the French. They moved

according to a seasonal subsistence economy---fishing in the summer, harvesting wild rice

in the fall, hunting, trapping, and ice fishing in the winter, and tapping maple syrup

(see below) and spearfishing in the spring. Their main building material, wiigwaas

(birch bark), could be transported anywhere to make a wiigiwam (lodge shelter).

Social organization was somewhat egalitarian, and women played a strong economic role.

Source: Unknown

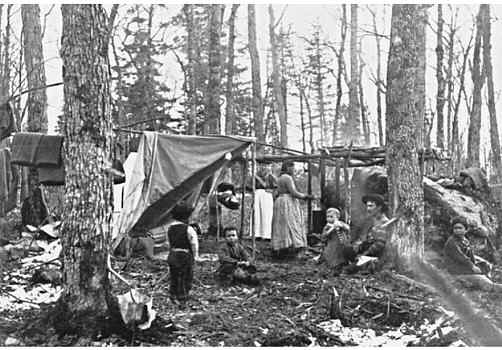

Ojibwe Indians in a maple syrup camp

The manufacture of sugar was one of the principal Indian industries. They

produced large quantities of this article, and of good quality. Having completed its

manufacture for the year, they packed it in mokoks (vessels or packages neatly made of

birch-bark) and buried it in the ground, where it was kept in good condition for future

use or sale. Their sugar-making resources were, of course, almost unlimited, for groves of

maple abounded everywhere.

Once a year, soon afer sugar-making, nearly all the Indians of

the interior repaired to Kepayshowink (the great camping-ground) which was where Saginaw

now stands. They went there for the purpose of engaging in a grand jubilee of one or two

weeks’ duration engaging in dances, games, and feats of strength. Many an inveterate

Indian feud reached a bloody termination on the "great camping ground" at

Saginaw.

Source: Unknown

It has already been mentioned that the ancestors of the later Saginaw Chippewas imagined that the country which they had wrested from the conquered Sauks was haunted by the spirits of those whom they had slain, and that it was only after the lapse of years that their terrors became allayed sufficiently to permit them to occupy the "haunted hunting-grounds." But the superstition still remained, and, in fact, it was never entirely dispelled. Long after the valleys of the Saginaw, the Shiawassee, and the Maple became studded with white settlements, the Indians still believed that mysterious Sauks were lingering in the forests and along the margins of their streams for purposes of vengeance. So great was their dread that when (as was frequently the case) they became possessed of the idea that the munesous were in their immediate vicinity, they would fly, as if for their lives, abandoning everything, - wigwams, fish, game, and peltry, - and no amount of ridicule from the whites could induce them to stay and face the imaginary danger. "Sometimes, during sugar-making," said Mr. Truman B. Fox, of Saginaw, "they would be seized with a sudden panic, and leave everything, - their kettles of sap boiling, their mokoks of sugar standing in their camps, and their ponies tethered in the woods, - and flee helter-skelter to their canoes, as though pursued by the Evil One. In answer to the question asked in regard to the cause of their panic, the invariable answer was a shake of the head, and a mournful ‘an-do-gwane’ (don’t know)." Some of the northern Indian bands, whose country joined that of the Saginaw Chippewas, played upon their weak superstition, and derived profit from it by lurking around their villages or camps, frightening them into flight, and then appropriating the property which they had abandoned. A few shreds of wool from their blankets left sticking on thorns or dead brushwood, hideous figures drawn with coal upon the trunks of trees, or marked on the ground in the vicinity of their lodges, was sure to produce this result, by indicating the presence of the dreaded munesous. Often the Indians would become impressed with the idea that these bad spirits had bewitched their firearms, so that they could kill no game. "I have had them come to me," says Mr. Ephraim S. Williams, of Flint, "from places miles distant, bringing their rifles to me, asking me to examine and resight them, declaring that the sights had been removed (and in most cases they had, but it was by themselves in their fright). I have often, and in fact always did, when applied to, resighted and tried them until they would shoot correctly, and then they would go away cheerfully. I would tell them they must keep them where the munesous could not find them."

A very singular superstitious rite was performed annually by the Shiawassee Indians at a place called Pindatongoing (meaning the place where the spirit of sound or echo lives), about two miles above Newburg, on the Shiawassee River, where the stream was deep and eddying. The ceremony at this place was witnessed in 1831 by Mr. B. O. Williams, of Owosso, who thus describes it: "Some of the old Indians every year, in fall or summer, offered up a sacrifice to the spirit of the river at that place. They dressed a puppy or dog in a fantastic manner by decorating it with various colored ribbons, scarlet cloth, beads, or wampum tied around it; also a piece of tobacco and vermilion paint around its neck (their own faces blackened), and after burning, by the river-side, meat, corn, tobacco, and sometimes whisky offerings, would, with many muttered adjurations and addresses to the spirit, and waving of hands, holding the pup, cast him into the river, and then appear to listen and watch, in a mournful attitude, its struggles as it was borne by the current down into a deep hole in the river at the place, the bottom of which at that time could not be discovered without very careful inspection. I could never learn the origin of the legend they then had, that the spirit had dived down into the earth through that deep hole, but they believed that by a propitiatory yearly offering their luck in hunting and fishing on the river would be bettered and their health preserved."

Click here for full size image (210 kb)

Source: Unknown

The decline of the fur trade transformed the traditional Ojibwe

society. When the British ousted the French from the region, the Ojibwe allied with

British traders and soldiers to drive away American settlers. After the US took control of

the region, however, the Ojibwe fell on hard economic times. The men took menial

jobs in the timber industry, and the role of women weakened. Nevertheless, the

bands’ isolation enabled the Ojibwe to preserve much of their religion and cultural

traditions through the 19th and into the 20th century.

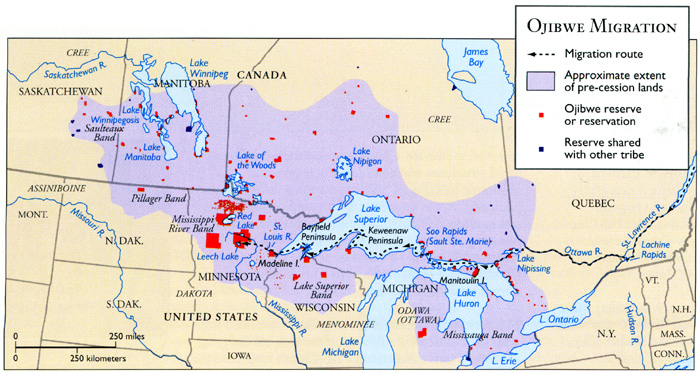

Starting about 1640, many Ojibwe moved (or were driven) westward from

the Sault Ste. Marie area. Some turned south into the Lower Peninsula, later joining the

Odawa (Ottawa) and Potawatomi in the Three Fires (three

brothers) Society. Others continued west along the Lake Superior shore and settled

on Madeline Island (in Lake Superior) about 1680. The map below shows not only where

the Ojibwe peoples lived prior to European settlement, but also where they migrated to and

where they eventually settled (on reservations).

Source: Atlas of Wisconsin

Many Ojibwe eventually migrated westward and southward along river

systems confronting the Dakota (Sioux) in bitter battles. They exchanged furs for firearms

and other European implements. Many French fur traders married into and adopted

Ojibwe culture.

Click here for full size image (436 kb)

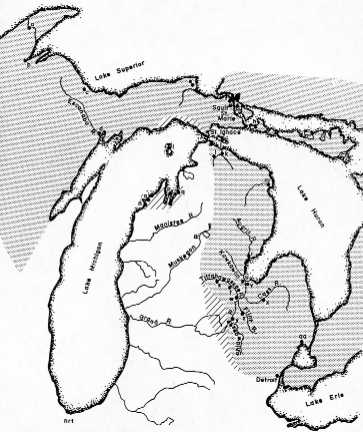

OJIBWE VILLAGES AND OCCUPIED LANDS IN 1820

Source: Unknown

Some of the text on this page is excerpted from the HISTORY OF SHIAWASSEE AND CLINTON COUNTIES, MICHIGAN (1880) by D.W. Ensign & Co.

This material has been compiled for educational use only, and may not be reproduced without permission. One copy may be printed for personal use. Please contact Randall Schaetzl (soils@msu.edu) for more information or permissions.