The earliest lumbering in Michigan was done by the French in order to build forts, fur-trading, posts and missions. The British, and later the Americans, used Michigan’s hardwoods to build merchant and war ships. Beginning about 1855, white pine became the most desired tree species by the lumber industry of the Great Lakes states. Navigable rivers and extensive pine forests formed the basis of a flourishing pine industry in Michigan’s Lower Peninsula until 1895, and about 10 years longer in the Upper Peninsula. Pine logging in the Lake States was essentially completed by 1900, following which the lumbering of hemlock and hardwood species begin to gain in importance.

The pioneer settlers of the 1820s found a land covered by dense stands of virgin timber; scarcely 50 years later, Michigan was the leading lumber producer in the nation. The clear-cutting was so extensive that by 1910, the once-abundant forests had almost completely vanished. Yet for the brief time that lumber was king, Michigan prospered and grew.

The first group of people to set up lumbering operations were from New England, especially Maine and New York. The forests there were almost entirely cut, so the owners and experienced crews followed the work. Many felt that the huge forests of Michigan would last for many, many years, yet within a 20 year period, 1870 to 1890, most of the trees were cut. The first people to understand the immensity of the woods were the government surveyors, but their job was to get information about the topography. The timber cruisers worked for the lumbermen and would select the best land available and reserve it at the land office for their employers. Much of this land sold for as little as $1.25 an acre; and later, under the Homestead Act (1862), men were hired to claim a plot of 160 acres and stay until the timber on it was cut.

The migration of loggers, sawyers, rivermen, and investors in timber from Maine to Michigan, then to Wisconsin, Minnesota, and the far West played a vital role in the development of significant portions of the nation. One writer on the American frontier states that Michigan had nine times as many varieties of trees as Great Britain, but he fails to note that one of them was the white pine, the lumber from which was highly regarded because of its beauty and the ease with which it could be worked. In 1847, a shipment of white pine lumber from Saginaw reached Albany, New York where it was compared favorably with lumber produced in Maine, which was then the standard of high quality. Shortly afterward, investors began the process of acquiring tracts of timber in Michigan, and the migration of workmen, with their skills and tools, got underway.

The "shanty boys" and the "timber barons" of the lumbering era were some of the most colorful characters in Michigan’s history. Tales of the lumberjacks’ prodigious strength and of the company owners’ opulent houses and manner abound, but the lumbering industry produced more than songs and legends. A vast amount of housing in the Midwest was constructed of Michigan timber, and the profits taken from the state’s forests were in turn used to fund a variety of enterprises around the state.

The original forest cover of Michigan had been greatly altered by agriculture, logging, and fire. When white settlement first began, 90% of the land area of the state was timbered. By 1840 farms were scattered over most of the southern hardwood belt and land clearing was producing more timber than was needed. Also, it was hardwood timber and not easily worked with the hand tools of the day. Much of it was burned simply to get rid of it.

Timber was utilized early in Michigan’s history. The hardwoods, although found throughout the state, were most prevalent in the Lower Peninsula; the softwoods, chiefly pine, were found in the northern Lower Peninsula and in the Upper Peninsula. The British and French built ships, forts, and other structures from local hardwoods, and each town had a sawmill to take care of its own needs. Commercial lumbering did not begin in earnest until the 1830s, however, when the rich pine forests of the Saginaw Valley became the backbone of the emerging industry.

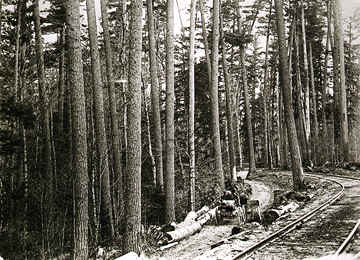

Geographic factors played an important part in the development of Michigan’s lumber industry. White pine, the wood most in demand for construction in the 19th century, grew in abundance in northern Michigan forests. The state was also crisscrossed by a network of rivers which provided convenient transportation for logs to the sawmills and lake ports.

By 1840 it was apparent that the traditional sources of white pine in Maine and New York would be unable to supply a growing demand for lumber. Michigan, the next state west in the northern pine belt, was the logical place to turn for more lumber.

Michigan's white pine stands were truly a tremendous resource and an awesome sight.

Source: Photograph by Randy Schaetzl, Professor of Geography - Michigan State University

The pine grew primarily as pure stands, on sandy, dry soils in the northern 2/3 of the

state.

Source: Unknown

North of an imaginary line from Muskegon and Saginaw, the pines grew: white,

jack and red, as well as other conifers. It was the white pine that allowed

the heyday of the lumber industry. Many white pines were over 200 years old,

200 feet in height and five feet in diameter. Michigan�s pine became

important as the supply of trees in the northeast was used. By 1880,

Michigan was producing as much lumber as the next three states combined.

But as magnificent as these stands were...

Source: Unknown Source: Photograph by Randy Schaetzl, Professor of Geography - Michigan State University

just as quickly they were gone (same image a few years later)...

Source: Unknown

The flood of pioneers to Michigan and the Midwest needed white pine for construction.

Michigan had it in quantities believed to be inexhaustible. Its harvest was inevitable,

and Michigan became the leading lumber-producing state in the nation, a position held for

a quarter of a century prior to 1900. This was the great, and now legendary, lumbering

era, an important period in our history, and one filled with romance and glory, as

well as tragedy. The wealth produced in this period was largely responsible for the great

financial and industrial rise of the state.

Initial logging/cutting satisfied local demand, but subsequent changes

in communication, urbanization, and transportation--particularly shipping on the Great

Lakes--soon caused rapid growth and expansion of markets in the Midwest. Throughout the

1840s, the market shifted east to such places as Albany and west to Chicago and the

prairie states, until most of the settled United States was receiving lumber from

Michigan. While the Saginaw region prospered in the eastern Lower Peninsula, the founding

of Muskegon in 1837 marked the west coast’s entrance into the lumber business. At one

time, the Muskegon River floated more pine logs than any other stream in the world.

Once under way, logging progressed rapidly. Significant

commercial lumbering began in Michigan in the 1830's with the appearance of sawmills and

increased dramatically during the middle decades of the 19th century.. By the 1870's

there were over 400 sawmills and 800 logging camps in the Lower Peninsula, mostly in the

pine region which extended from the Saginaw valley and the Muskegon area north to the

Straits of Mackinac. Many individual sawmills in 1882 were producing from 10-20 million

board feet of lumber per year. The industry grew rapidly from the 1850s

through the 1890s, encouraging the settlement of the state’s northern regions and

development of a wood products industry. The Saginaw Valley was the leading

lumbering area between 1840 and 1860, when the number of mills in operation throughout the

state doubled. By 1900 most of the pine in the Lower Peninsula was gone. Pine

logging in the Upper Peninsula began to assume importance in the 1880's and the virgin

stands lasted until about 1920. The peak of Michigan’s great timber harvest was

reached in 1889-1890 when mills cut a total of 5.5 billion board feet of lumber, mostly

pine. This is 10 times our present annual production of all species. White and red pine,

once the backbone of the industry, now make up less than 5% of the cut.

Many rivers, such as the Muskegon, that could carry logs quickly were

transformed into a valuable means of transportation. By 1869 Michigan was producing more

lumber than any other state, a distinction it continued to hold for 30 years. During that

time loggers penetrated and settled the interiors of both peninsulas and moved away from

the rivers in search of timber. Lumbermen became less selective as the years passed,

cutting inferior quality white pine and logging other kinds of trees in order to meet a

continuing demand for wood. In 1889-1890, the year of greatest lumber production, Michigan

produced approximately 5 � billion board feet.

Lumbering grew dramatically for three reasons. First, Treaties with

Ojibwe and other tribes made the timber lands available. Second, the agricultural frontier

was advancing westward into the treeless prairies, as waves of settlers arrived in

Illinois, Iowa, Kansas, and Nebraska. Finding rich soil but few building materials, the

settlers looked to the northwoods timber for their lumber. Third, and most important,

Michigan had an extensive network of waterways that flowed from the woods to the Great

Lakes, from which the logs and lumber could be shipped just about anywhere. The Saginaw,

Au Sable, Manistee, Escanaba, Muskegon, Thunder Bay and Menominee rivers (and their

tributaries) provided transportation for many of the harvested logs to mills and markets,

and provided power for the mills. Numerous sloughs, oxbows, lakes, and bays provided ideal

holdings areas for cut timber waiting to be milled and for building "log booms"

for sorting and storage.

Logging and milling had begun in earnest between 1830 and 1840. In

general, the pine lands and the central, southern, and eastern areas were logged first and

most completely, and were then subject to damaging fires which

followed. These were the drier sites which had most pine to begin with, and were so

situated and continuous as to be in the paths of many fires which raced from west to east

with the prevailing winds. These were also the areas in which ill-advised agricultural

efforts, encouraged by land speculators, stimulated land clearing by early settlers.

Patches of timber of varying size, protected on the west by either open water or wet

swamps, or, to a lesser extent, hardwood sites, escaped some of the fires which swept

around them, but sooner or later many of these burned too.

Source: Unknown

High Plains logging

Some of the largest and best pine stands in Michigan were in the area known as the

"High Plains" (the High Plains are the high, sandy areas near Grayling and

Gaylord). In the 1850's "land lookers" were busy in the High Plains area

locating and filing land claims on choice timber acreage. There were still no settlements

in the pine country except along the lake shore but the Land Office Survey had been

through the country and had marked the township and section lines.

Occasionally two parties of "lookers" would meet in choice timber country and a

spirited race would follow, the destination being the Land Office at Ionia, two hundred

miles south. Previous to 1820 the price of public lands at the Land Office was $2.00 per

acre, on the installment plan, 50 cents down and 50 cents per year. In 1820, due to the

"cost and difficulties of collecting arrears" and "to check

speculation," the policy was changed to that of the sale in 80 acre plots at $1.25

per acre, for cash.

A lively speculation in timber lands grew up, although most of these

were beyond the reach of lumbering for the time being. At the price of $1.25 per acre

there was heavy profit in the timber lands. The average yield of timber from the Michigan

pine lands was 5,000 board feet at an average stumpage value of $3.00 per thousand. In

addition these early lands were not average, some of those on the western side of the High

Plains yielded almost 30,000 board feet per acre. A township near Houghton Lake was sold a

few years later for $100,000, which was probably less than half the stumpage value of the

timber on it. The pine of Michigan made more millionaires than the gold of California.

The earliest lumber operations in the High Plains were along the

principal rivers, especially the Au Sable, Manistee, Muskegon and their tributaries. From

Saginaw Bay, the mill owners had extended their operations up the east coast. In 1863

Loud, Gay & Co. had a mill at Oscoda at the mouth of the Au Sable and owned 60,000

acres of pine along this stream. There was a mill at Alpena as early as 1860 drawing upon

the timber up the Thunder Bay River. On the western side, logs had been driven down the

Muskegon for shipment to Chicago in 1839 and there were mills at Muskegon and at the mouth

of the Manistee by 1850.

By 1860, lumbering was second only to agriculture as the state’s

principal means of livelihood, and the industry created new towns, new railroads, new

jobs, and new profits. The excellent reputation of Michigan pine initially attracted

thousands of lumbermen from the cutover forests of Maine and elsewhere in the East, but

later, Scandinavians, French Canadians, and Irishmen all flocked to Michigan with dreams

of wealth and riches. Unfortunately, of the countless numbers who tried, few people really

made their fortunes from Michigan timber, and those few were often eastern lumber barons

whose interests lay more in personal gain than in public economic development. Huge and

elaborate mansions in fashionable towns such as Petoskey and Cheboygan stand as testaments

to the opulence of the timber boom, but staggering profits were the exception, not the

rule. Most of the small operators struggled to survive recessions, panics, and a

devastating Civil War; bankruptcies were common. Lumber workers, too, suffered

disillusionment. Unhappy with their pay, they made unsuccessful attempts to strike and to

unionize. With no alternative employment options available, these attempts were doomed to

failure.

Parts of the text above have been paraphrased from C.M. Davis’ Readings in the Geography of Michigan (1964).

This material has been compiled for educational use only, and may not be reproduced without permission. One copy may be printed for personal use. Please contact Randall Schaetzl (soils@msu.edu) for more information or permissions.