LOGGING PIRATES

Forests and rivers remain an important part of Benzie County’s economy. They provide

recreational attractions for camping, hunting, fishing and other outdoor activities.

During the lumbering heyday, between 1870 and 1920, vast stands of virgin timber fell to

the axe and were sent down rivers and across lakes to the many mills scattered around the

county.

Then, like now, dry weather had potentially devastating affects on our

rivers and lakes. Now there are recreational and commercial boating concerns. During the

lumbering era there were other "traffic" problems. The biggest headache for

moving logs down river was low water levels. Delays that played most havoc with log

transport were those due to lack of water for flotage. When it was dry and water was down,

great difficulties were experienced in driving logs downstream not only here in Benzie

County, but all over the state. This caused many mills to sit idle.

In 2000, the low waters of the Betsie were not causing concern about

log drives. Low water levels in Betsie Bay are revealing logs pushed against the southeast

shore along the M-22 causeway. Among these logs are some treasures, says Dean Luedders,

president of the Benzie Area Historical Society. There are pirate log ends, scattered

among the logs and driftwood piles along the southeast shoreline. Pirate log ends are

pieces sawed off with log marks by a thief. During the logging days, some unscrupulous

characters, would cut off one company’s log mark, or brand, and remark the log with

another company’s mark so they could steal it.

Source: Unknown

In the woods of Benzie County, dozens of logging operations would cut millions of board

feet of timber. Many of these were transported to the many mills along the streams,

including the Platte River and Betsie River. Moving logs from the forest to the mill would

be handled by driving and sorting crews. Laws in the early 1850s provided equal rights to

lumber companies and all persons using the rivers to float logs. As lumber activity

increased, logs became mingled in rivers. It was hard to distinguish owners and some

spilled their logs into the river forcing others to transport them downstream for a free

ride. Laws became necessary for smoother operations. Bark marks, brand slashed along sides

of logs, no matter how clear or simple, could not be sorted quickly enough with thousands

of logs coming down river. Trying to read these marks, it frequently was necessary to turn

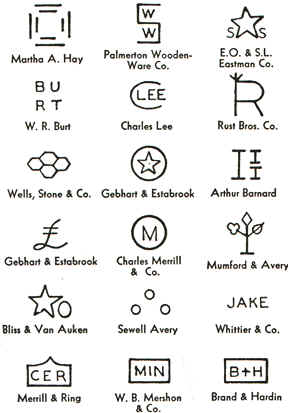

logs over in the water. Finally, in 1859, a law required log owners who floated logs to

mark the ends of their logs and to register these marks with the counties. End marks

worked far better. They were stamped into the log ends with heavy marking hammers. Each

end was marked in several places so the brand was always easy to spot.

This 1859 law had a provision also to deal with log thievery.

So many logs floating freely, representing easy money, were described

as a constant temptation to thieves. Marks were often obliterated or cut off in order to

give stolen logs another brand. In time, companies that transported logs down the river

were confined to work just one river, and owners of logs floating them on the river were

required to register their marks in the counties through which the stream passed.

Log marks became not only devices of orderly transportation of timber

to mills, but representatives of law in maintaining equities among the men who harvested

timber. On the Betsie, although it was controlled by the Whitman Boom Company, one

operator handled the drive.

The Betsie River never had a large volume of water, so its drives

depended heavily upon spring rains. The upper river was particularly poor, and, because

some of the stands of pine were around Green and Grass lakes, source outlets to the Betsie

River, special booms were devised to move logs across the lakes to other outlets. Before

logs entered the river, there was preparation work. An efficient drive required the

waterway channels to be cleared of rocks and trees that might catch logs and create a

dreaded jam. Often dams were built in the headwaters to control the flood stages, so that

a series of artificial freshets might be available to carry logs, rather than one big

natural flood that might leave some of the valuable timber behind to wait for the next

year’s flood.

A short-haul railroad was built to get

pine from the Karlin Hills south of the lakes, down to the main stream. Rail cars making

15 or more trips daily would carry about 100,000 feet of pine. In preparing to drive logs

on the Betsie logging companies were forced to raise a three foot head of water to carry

the big drive through to Betsie Bay.

Log marks are a part of Michigan’s logging past. Log marks are to

Michigan what cattle brands are to the grazing states of the West: symbols of order in a

romantic industry that would have been chaotic without them.

From the Benzie County Record Patriot (March 22, 2000)

This material has been compiled for educational use only, and may not be reproduced without permission. One copy may be printed for personal use. Please contact Randall Schaetzl (soils@msu.edu) for more information or permissions.