Human intervention, such as harvesting, fire and clearing for development, has profoundly affected the composition of Michigan’s forest base. While the area of forest coverage has generally rebounded since the timber boom period of the last century, few regions of the State contain the same mixture of tree species that existed prior to settlement.

This section is about the basic economic values involved in forestry, such as jobs and wages, but to many people the most important aspects of the forests lie in the beauty to be enjoyed, the deer and grouse to be seen and hunted, or the flowers, berries, mushrooms, birds, and a multitude of other things found therein. Every one of these items is a part of the forest. None are separable. The forest at work can provide all of these benefits in bountiful measure while producing the economic wealth which makes it possible for people to enjoy them.

Although it is an old story, the history of the forest resources and industries in Michigan must be kept in mind in order to appraise its present condition and value, to know why and what the present industrial activities are, and to see the possibilities and probabilities of the near future.

As can be said of every forest area east of the Rockies, and most of those farther west, Michigan is a "cut over" area. This term to most people implies something that is/was destroyed, but forests are a renewable resource, and Michigan’s forests have both feet firmly planted on the road to recovery. There is very little likelihood of interruption in the future of a steady improvement in the forest wealth and benefits it produces in Michigan.

Except for occasional inaccessible patches, and a few areas which were reserved from cutting, the virgin forests of Michigan are essentially gone. The few remaining areas of old hardwood timber which are still available to loggers have long ago yielded the big pines.

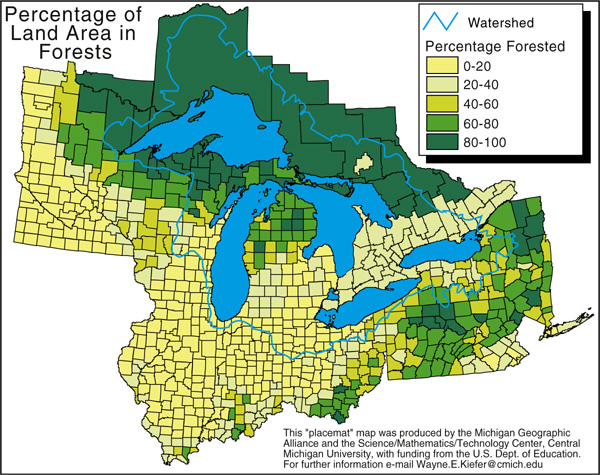

Content, rather than size, has defined postsettlement forest change in the northern lower peninsula and upper peninsula. Pine, and pine-oak species flourished throughout drier areas in the north, with smaller areas of hemlock, birch, and spruce. Logging and a series of destructive fires decimated virgin pine forests, leaving previously minor species such as aspen and birch as dominant species. In many areas, paper birch, jack pine, oak, and maple survived; they were either able to sprout from soils scarred by fire, or were considered less valuable as timber and thus not harvested. In some areas, these early-successional species grew to dominate new forest growth, favoring wildlife populations such as whitetail deer. Large-scale planting programs helped re-establish species of pine in many forest areas. The map below is a composite image that shows percentage forest on the landscape. Greener areas are more densely forested.

Source: Unknown

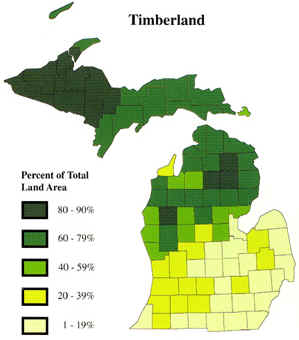

Note (below) that most of Michigan's densely-forested land is in the western UP, where over 90% of the surface is forested.

This "placemat" map was produced by the Michigan Geographic Alliance and the Science/Mathematics/Technology Center, Central Michigan University, with funding from the U.S. Dept. of Education. For further information email Wayne.E.Kiefer@cmich.edu

Forest cover varies widely throughout the State. Major cover types combining tree

species found together are often used to describe cover conditions. The oak-hickory, elm-ash-silver/red maple, maple-birch, and aspen-birch cover types currently

represent 3/4 of all timberland area. The maple-birch group alone accounts for 38%, or 7.1

million acres, increasing by 17.6% between 1980 and 1993. Another similar group,

aspen-birch, occupied nearly the same area in 1955 but has since decreased to 17% of the

total timberland. Softwoods such as white, red and jack pine continue to grow at levels

smaller than hardwood groups in an area of 1.9 million acres--one tenth of the total

timberland area.

Much of the post-timber boom forest cover has reached maturity. Overall

timberland resources in the State are composed of 25% softwood and 75% hardwood. Nearly

one-quarter of all standing growth (in 1995) consisted of sapling-sized trees; larger

pole-timber-sized trees occupy 30%, and the larger sawtimber-grade trees account for 46%

of timberland. The maple, beech and aspen groups predominate, followed by spruce-fir and

oak-hickory. Changes in composition for 1980 to 1993 are reflected by decreasing species

groups such as aspen-birch.

This "placemat" map was produced by the Michigan Geographic

Alliance and the Science/Mathematics/Technology Center, Central Michigan University, with

funding from the U.S. Dept. of Education. For further information email Wayne.E.Kiefer@cmich.edu

The proportion of Michigan’s rural landscape that is forested today is fairly

stable, or slowly increasing. Forest land, as a percentage of the landscape, is

lowest south of the tension zone. There, the agricultural potential, as well as land

values, is relatively high, and much of the land that was originally cleared for

agriculture is cultivated. The remaining woodlots, have been left when they are on

less-than-choice land thought too rocky, sloping, wet, or otherwise unsuited for

agriculture. Few of these woodlots have remained uncut as nearly all have been subject to

at least occasional firewood culling and many have been grazed, a practice that interrupts

normal regeneration within the woods. The most extensive woodlands today are generally

under state ownership (game areas) and were among the least attractive for agriculture

because of various physical limitations.

Source: Unknown

North of the tension zone, the amount of woodland increases

significantly, signaling a decline in agricultural potential because of the greater

sandiness and acidity of the soils combined with the cooler summers and a shorter growing

season. Pockets of better soil have remained in cultivation since lumbering activity

ceased, but the poorer soils have been left to forest regeneration after brief episodes of

farming. The proportion of forested landscape decreases westward toward Lake Michigan

where dairying and fruit growing, particularly, become more economically attractive. In

the Upper Peninsula, nonforest land is the exception, and, again, it corresponds to the

patches of better soil or is located near urban markets where dairy produce is in some

demand. In many areas across the entire state, farmland continues to be abandoned because

of increasing farming costs, and fields that have not been cultivated for only ten to

fifteen years are slowly reverting to a woody condition.

Parts of the text on this page have been modified from L.M. Sommers' book entitled, "Michigan: A Geography".

This material has been compiled for educational use only, and may not be reproduced without permission. One copy may be printed for personal use. Please contact Randall Schaetzl (soils@msu.edu) for more information or permissions.