The October 15, 1908 Metz

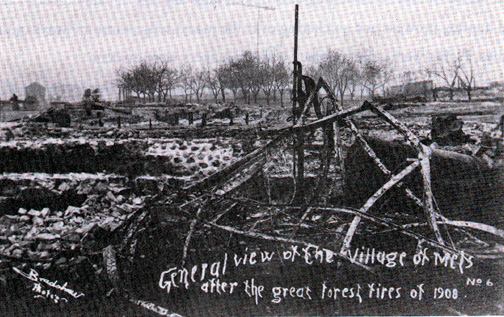

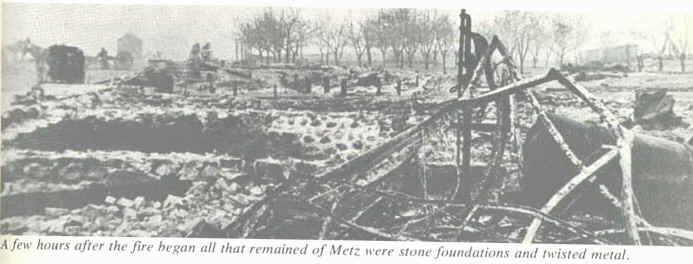

Fire. The image below shows all that was left of the village of Metz (in

Presque Isle County), after its major fire. The fire essentially burned the village

to the ground. As some said, "Metz vanished". All that remained was

blackened rubble. Metz had become the victim of the forest fire that immortalized its

name. Before the Metz fire burned out on the shores of Lake Huron, it had killed 42

people, destroyed over 200,000 acres in Presque Isle County alone and helped arouse

concern that resulted in Michigan’s first effective forest fire prevention and

control measures.

Source: Betty Sodders, Michigan on Fire

The setting.

Climatic conditions in the NE lower peninsula were at their worst since

the scores of devastating fires that had swept across the Thumb of Michigan during the

fall of 1881. The year 1908 began with a wet spring, which caused forest undergrowth to

flourish dramatically. The warm humid weather with frequent warm rains, covered a long

period during the early summer season. The late summer was extremely dry and hot,

withering the plants. The deficiency in rainfall for the months of July, August, September

and October in that year was shown to be greater, in the records of Michigan Agricultural

College, than for the same months of any year since 1864, when the meteorological station

at the college was established. In late August and early September, several light

frosts turned the larger than normal ferns, weeds and other plants into powdery

kindling---eagerly awaiting an opportunity to feed and fuel a pending disastrous fire.

Several killing frosts occurred in the Upper Peninsula on October 2 and in the

northern counties of the Lower Peninsula on October 3. These frosts added dead hardwood

leaves to the dry, already dead undergrowth, and the hot dry weather following, with hot

southerly winds, produced a condition for fires not before occurring in Michigan.

Drought was widespread. Chisholm, Minnesota was destroyed when

encroaching flames ate up 20,000 acres. Isle Royale was not immune to adverse weather

conditions. Uncontrollable fires swept the island, which was the home to native Michigan

moose, threatening their natural browse as well as their very existence. Weather-wise, the

stage was properly set for disaster at the small turn-of-the-century village of Metz.

Thus, on October 14, 1908 the very air seemed to be charged with inflammable gases.

What was Metz like before the fire?

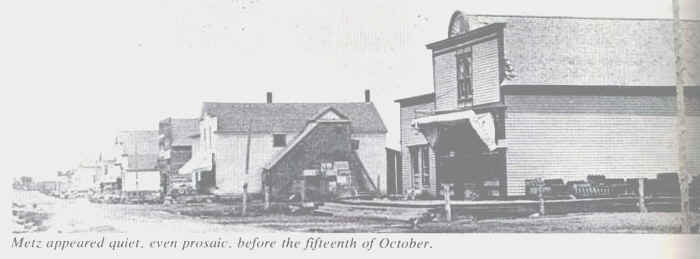

The township of Metz had been founded in 1878 and drew its strength

from a sturdy stock of Polish and German immigrants. By 1900 more than 600 families

resided in and around the village of Metz. In addition to scores of neat homes, this

railroad shipping center also proudly sported three hotels, three general stores, a

boarding house, a shingle mill, a sawmill, livery stables, a blacksmith shop, three

saloons, plus a post office and train station. Two trains passed through Metz in

each direction, and a person could travel to Alpena or Cheboygan and return the same day.

The village was the hub of surrounding farm and lumbering areas. Most

of the men in Metz were farmers, lumbermen or both. Most of the men in Metz were

farmers or lumbermen; some did both, working their farms in the summer and the forest

during the winter. If they were not cutting down trees, they might be peeling hemlock bark

used to create tannic acid at the Alpena tannery. At the sawmill near the railroad tracks

were piled stacks of logs, railroad ties, cedar posts and poles as well as hemlock bark

for tannery use; all waiting for shipment by rail to market sources. Space was limited, so

additional wood products were stacked on cutover land directly across the road from the

village.

Source: Betty Sodders, Michigan

on Fire

The Detroit & Mackinac Railway was the town’s focal point, for

it not only brought business to town, but offered easy accommodations to both Cheboygan

and Alpena as well. Two trains traveling in both directions stopped daily. At the sawmill

next to the tracks stacks of logs, posts, poles, ties and hemlock bark waited to be loaded

onto railroad cars for shipment. Because space near the sawmill was limited, large stacks

of logs, posts and ties lay across the road from the village on cutover land.

The origin of the fire.

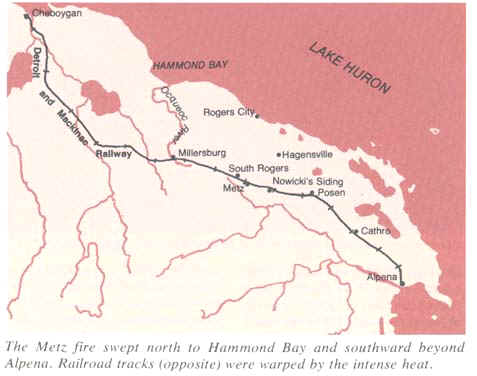

The blaze originated from an out-of-control brush fire near Millersburg

(a few miles to the west) where workers were clearing land. The fire spread southeastward

to portions of Alpena and Alcona counties before it eventually died on the shores of Lake

Huron.

Strong winds evidently upgraded this smoldering of debris into a

full-fledged inferno cutting a swath some 30 miles long by three miles wide on a course

that ended only when the flames reached the shores of Lake Huron. From there, a sudden

wind shift turned this conflagration westward, traveling toward the ill-fated village of

Metz. Other sources reported the fire was mainly due to flying sparks passed off from a

D&M passenger train.

Source: Betty Sodders, Michigan on Fire

Thus, the Metz fire, bad as it was, was not simply a localized

conflagration. The blaze may have started near Millersburg and traveled toward Lake Huron,

only to double back again. During the course of days, fire also threatened the towns of

South Rogers, Nagel’s Corner, Hagensville, Hammond’s Bay, Cathro and Liske.

Facts about the fire

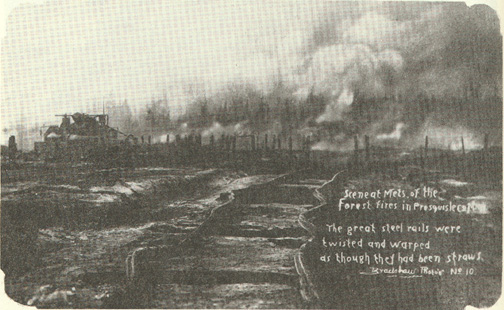

The worst tragedy of the Metz fire was the derailment at Nowicki’s Siding, about two

miles south of Metz along the Detroit and Mackinac Railway. There, large quantities of

hemlock bark and cedar posts, ties and poles were stored before being loaded onto railway

cars for shipment.

A train, composed of an engine, a coal car, a gondola (an open flat car

with sides) and several other cars, had arrived at Metz in the early afternoon. As the

fire approached, about 30-40 men, women and children climbed into the gondola, while

salvageable goods were loaded into the other cars. It was dark on the 15th of

October when the train left Metz. Engineer Foster later recalled what happened when the

train reached Nowicki’s Siding:

A little farther on we came out of the woods, and here on a siding a number of cars loaded with tanbark were standing. On the other side of the main track were piles of cedar posts and the bark and posts were all on fire, though I didn’t know it until we were right between ‘em. Then the engine went off the track. The rails had been warped by the heat (see photo below). We couldn’t have stopped in a worse place for those that were on the engine. There was fire on each side, and the car of bark back of the tender was burning fiercely...

Foster and the fireman climbed into the tender’s water tank. Shoulder deep in the

water, they splashed each other to get some relief from the smoke. When they felt that the

heat was less intense, they decided to leave the tank for safety. Foster jumped out and

walked along the tracks to Posen, about three miles distant. The fireman never made it out

of the tank.

Source: Betty Sodders, Michigan

on Fire

Back in the gondola, Arthur White of Metz lifted his nephew over the

side and got out himself. He could not find his brother, but picked up the lad and made it

to an open field. Jerry Annis, station agent at Metz, had put himself, his wife and their

baby on the train. They climbed out of the car, dashed into a ditch and crawled to the

small open field where they dug away the top dirt and ashes with their hands and held

their faces in the earth. Frank Becker of Pontiac, a salesman visiting customers in Metz

at the time, escaped by leaping out of the gondola and blindly groping through the smoke

to the open field. He lay there until about 3:00 a.m. When the fire subsided and the smoke

began to clear, he found himself among a group of nearly 30 others.

Press reports.

MILLERSBURG, Oct. 16-The Detroit News correspondent has been on the scene of the

Metz fire and has just returned. Fifteen men, women and children burned to death in the

awful fate of the victims of the worst fire that this section ever knew.

These people were all on a train which tried to take them out of Metz,

most of which last night was a raging volcano. The train was made up at Metz late in the

afternoon when the fate of the town was evident, and there was no other avenue of escape.

The train was composed of eight or nine wooden cars, and one steel gondola. Into this open

car were crowded 30 or 40 men, women and children with a mass of household effects. They

had gone for a mile or so out of Metz towards Posen and safety. Then at Nowicki’s

siding the rails spread (due to the heat) and the engine went into the road-bed and

stopped. On either side of the track were piled immense quantities of cedar ties, posts

and poles, hemlock bark and other forest products.

The flames swept over the doomed train, setting it on fire, igniting

the household goods in the car with the people. Many jumped and tried to make their way to

safety, and most of these succeeded, although fearfully burned.

Three mothers and nine small children stayed in the steel car whose

sides were red hot and they were cremated. Their remains were identified only by objects

on their bodies which fire could not destroy. Art Lee, the fireman, sought safety in the

water tank on the engine, and was literally boiled to death. Wm. Barrett, the brakeman,

died on the engine. The charred remains of John Nowicki were found on the road crossing

the track just ahead of the engine.

Train Stopped In A "Hell Of Flame"

POSEN, Oct. 16-Arthur White, of Metz, one of the survivors of the fire, tell the News

correspondent the following story of the disaster. "All went well until we reached a

point about a mile out of Metz. Then we ran into a regular hell of flames and smoke, which

swept over the open car, setting our clothes on fire and singeing our hair. All of a

sudden the engine went off the track and we stopped right in the midst of a mass of flames

which surrounded us. My brother and his little boy were next to me. He said we must get

out of this. I lifted the lad over the side of the car and dropped him and got out myself.

I couldn’t find my brother, but I picked up the boy and struggled through the flames

and smoke to an open field.

Trainmen Jump In Water Tank

BAY CITY, Mich., Oct. 16-The latest information from the forest fire along the Detroit

& Mackinac Railway is to the effect that a relief train sent from Alpena last night to

aid the people at Metz, 25 miles north of that place, was destroyed by flames and 16

people burned to death. According to a message received by D&M officers here, the

train left Alpena, reached Metz, took the people and household goods on board, and started

north toward Cheboygan. When the train reached Hawks Station it found fire on both sides

of the track and was unable to proceed. It then started back, intending to go to Alpena

with the sufferers. After passing Metz the train ran off the track near Pulaski, the fire

having burned the ties and spread the rails.

The forests on both sides of the track were ablaze, and the train soon

caught fire. There was no escape for the passengers, and they were burned to death. The

engineer and fireman took refuge in the water tank of the locomotive, but were soon forced

to flee, and were also caught by the flames and burned to death.

Alpena, Fighting To Save Itself, Awaits Return of Rescue Train

ALPENA, Mich., Oct. 16-Seventeen persons are known to be dead, and scores of others may

have been lost in the forest fire which has swept across the D&M railway at Metz. The

dead are mostly women and children, though two trainmen are also known to have perished.

They burned up in a steel gondola car when the relief train of which it was part left the

rails and was trapped in what must have been a sea of flames. Some survivors have reached

Posen, a station of the line about 30 miles from here. Posen appears to have marked the

southern edge of this fire belt; Millersburg, the northern. A special train with coffins

and a corps of doctors has been sent from here.

Engineer William Foster and conductor John Kinville were with the other

men when the dash for liberty was made, and the latter succeeded in breaking through the

fire and into the open, but their comrades were overcome by smoke and fell exhausted to

the railroad track. Their bodies have been recovered. Engineer Foster is terribly burned,

is blind, and may not live. Station Agent J.E. Annis of Metz is in the same condition. It

cannot be definitely learned how many perished in the fire which destroyed the relief

train.

A telephone message from Posen states that 16 dead bodies have already

been taken from the wreck, all of which are charred almost beyond recognition. A second

relief train has been sent to the scene with food and medical assistance. It is feared now

that many lives were lost at Metz when the town burned, as all avenues of escape were cut

off before midnight. Communication with Posen is cut off and details cannot be obtained

until the relief train returns to the city.

Mr. and Mrs. Nowicki, an aged couple who lived in the village of that

name, roasted alive in their little house near the railroad tracks.

The train which burned had been sent from Hawks Station to take out the

people whose lives were threatened by the encroaching forest fire and the train was

derailed by the spreading of the rails, due to heat. What scenes of horror must have

followed when the terror-stricken refugees found themselves helpless amid the fire from

which they had been fleeing are not yet known. Conductor Kinville and Engineer Foster

managed to crawl into Posen early this morning on their hands and knees, both badly

burned. No story has been obtained from them yet, owing to lack of wires. Only the bare

report that they are alive and in the village has come out.

From Millersburg, about noon, came the first positive confirmation of

the fate of at least a part of the train’s passengers. It was but a brief statement.

It said that 17 burned skulls had been found.

These are the first reports of the Metz tragedy as they filtered in.

The shock of them horrified the citizenry of Michigan. As the day passed, more details

came forth, such as the following account from a Pontiac survivor of the rescue train

disaster:

"We Lived In A Sea Of Flames!"

Frank Becker Tells His Experience in Getting Out of the Doomed Town Last Thursday

Afternoon

PONTIAC, Mich., Oct. 17-Frank Becker, a traveling salesman for the Mascot Cigar Co.,

was one of the passengers on the ill-fated relief train that was wrecked between Metz and

Posen. He arrived home this morning.

"No words can describe that awful night," he declared.

"I do not believe that any human beings ever went through a more terrifying

experience and lived. It was only by sheer luck that I myself escaped. I was in Metz,

which is one of the places that I make on my trips. All day Thursday the people were in a

state of nervous apprehension over the forest fires which seemed to be on all sides. When

the people from the surrounding country began to come fleeing in, abandoning their homes

to the mercy of the flames, it seemed time to get out. The station agent sent for a relief

train, and when it arrived about 5:30, we all hurried on board. There were about 40 or 45

people on board, I think. When we had gone about a mile and half from Metz we saw what

seemed to be a veritable furnace ahead of us. The woods, which came close to the track,

were a roaring mass of flames. It didn’t seem possible that we could get through, and

the engineer stopped the train. But the flames were closing in back of us and there was no

hope of going back. So he concluded to run for it. We covered up as best we could and

breathed only when it was absolutely necessary. On we went through the roaring, crackling

flames, which in some places were leaping clear across the track. The heat was awful. The

steel car in which we were riding became almost unendurably hot. Just as it seemed that we

couldn’t endure it any longer, we came out into a clearing place.

"We went on, with the flames on both sides of the track, but not

so close as to be dangerous. Then, when we were about half way to Posen, we saw another

stretch of red flame leaping high against the sky squarely in front of us. The engineer

stopped again. But on every side, not matter where you looked, there was the same angry

red glare. The flames were creeping closer and closer, and there seemed no place to

escape. We were in a sea of flames. He started the engine again and we dashed straight at

the flames. I had my head covered up, but I could hear the crackling and roaring and feel

the awful heat, when all at once there was a jar and we stopped. The engine had jumped the

track. It was everyone for himself. We were right in the midst of a roaring mass of

flames. The smoke was so thick that you couldn’t see three feet in front of you. I

wouldn’t have given much for my chances of life that minute. .

Source: Betty Sodders, Michigan on Fire

"As I leaped from the car I could hear the wailing of little

babies and the screams of women and children. Those sounds are still ringing in my ears.

Every time I dropped off to sleep last night I was awakened by those same shrill agonizing

shrieks. But there was nothing that we could do. It was everyone for himself, and I

wouldn’t have given a plugged nickel for my own chances of life at that moment.

Blindly staggering and groping my way through the choking smoke I ran a little way back

down the track. The others had scattered in all directions.

"I saw a dark place in the inferno of flames, and kicking over a

blazing fence, I made for it. It proved to be a small plowed field. I lay face downward in

the plowed ground and thanked God for the relief from that choking, blinding smoke. I lay

there for hours, scarcely daring to look up. I could hear others shouting around us, but I

didn’t know how many there were. Along about 3 a.m. the fire began to subside and the

smoke to clear a little. I looked around and found that there were nearly 30 in the field.

We were the only ones who escaped. We who had escaped went back to the train, which was a

smoking mass of twisted iron. Many of the women and children lay charred, blackened

corpses in the steel car. Some of them were the wives and children of men in our party,

and the grief of these men was something awful. We found the fireman in the tender of the

engine, literally scalded to death. The coal in the tender had caught fire, boiling him

alive. We walked on down the track and two miles down we found the engineer, burned to

death. I don’t know his name, but he was a brave man.

"I lost everything I had but the clothes on my back, but I think I

am the luckiest man in the United States. I escaped with scarcely a burn."

Source: Betty Sodders, Michigan on Fire

More details.

St. Peter’s Lutheran church was the first structure ablaze. Next, the piles of

hardwood ignited. These stood a mere 70 feet west from one of the town’s stores,

which also quickly burst into flames. One by one, homes and businesses were consumed by

fire-the sawmill, saloons, train station, Nowicki’s Hotel, livery stables, Centala

Brothers, Hardie Brothers and Konieczny Stores. In less than three hours time, Metz had

vanished.

One of the last men to leave the doomed community was the assistant

D&M station agent, George Cicero. The employee kept the telegraph wires open while

alerting a train that was ready to flee from nearby LaRoque, He kept them informed of

developments until the flames were nearly touching the depot. Cicero was tagged a hero by The

Detroit News, in a story with headlines full of pathos.

Other fires in the Metz area, that same year.

WEST BRANCH, Mich. Oct. 17-The forest fires have assumed most alarming proportions. The

city is hemmed in on three sides. The Michigan Central railroad has taken all cars

possible out of the branches and is sending an engine and cars to bring out the household

goods of all people in danger. Train crews are stationed at different points along the

line instructed to be ready at a moment’s notice. West of the city is a piece of

timber containing hundreds of acres of hardwood which is burning fiercely. Two small towns

on the branch railroad are out of provisions and are not able to have trains bring in

their supplies. Four men have gone blind from the smoke.

PETOSKEY, Mich., Oct. 17-A summer resort near Conway is threatened with destruction, forest fires creeping upon all sides. A pall of smoke hangs over Bayview, the big Methodist resort, but fires are not near enough to cause anxiety. East of Brutus, the fires are sweeping towards Riggsville.

CHEBOYGAN, Mich., Oct. 17-An immense tract of hardwood burned over, destroying the new

camps being built. The men escaped with only their clothes, and one horse, being driven

out last night at midnight, and compelled to run to the lake shore.

Lakeside resort has been burned, the groves and cottages. County

farmers are saving their homes, but all the stuff in the woods has burned. The Indian

Reservation south of Mullet Lake has burned over and the Indians are homeless.

HARRISVILLE, Mich., Oct. 20-A message was received this morning from Harrisville, seat of Alcona County, asking for help. The situation there is so critical that a shift in the wind will mean the destruction of the town. "Fire surrounds us on three sides," says one Harrisville deputy. "So far the wind has blown continually off the lake. This is all that has saved us. If it ever shifts, the town is doomed."

BLACK RIVER, Mich., Oct 21-The fire situation in Alcona Township is alarming. B.D.

Nicholson has lost his barn and his entire crops together with all his farm machinery.

Clarence Scriber’s farm house was destroyed and the family barely escaped with

their lives.

Black River, a station on the D&M, has been saved by the most

heroic measures, and is still surrounded with fire. Unless rain comes soon it is in great

danger of being wiped out.

SAULT STE. MARIE, Mich., Oct. 17-Nine towns in Chippewa County were saved by heroic effort. They are Rudyard, Soo Junction, Trout Lake, Brimley, Bay Mills, West Neebish, Detour, Raber and Gatesville. In response to an appeal from Point Iroquois, the government tug Aspen left to go to the assistance of the lighthouse crew who had been fighting the flames for hours. The last message stated that the lighthouse might be destroyed, as the woods were like a roaring furnace.

Devastation And Danger In Other Sections Of The County

It was Metz Township that bore the brunt of the conflagration, sustaining the greatest

loss of life, property loss, and other casualties, yet the townships of Belknap and

Pulawski were also hard hit. Over thirty farmsteads were completely destroyed in these

townships.

The gale winds that drove the fires in the southwestern part of the

Presque Isle County through the tinder-filled forests in a five-mile-wide swath in the

direction of Metz, also swept fire into Case and Allis townships and made an assault on

the village of Millersburg that fateful October 15. Citizens of Rogers City, too, battled

to save their village as the fires blazing through the county reached the forests around

the village.

The forest acreage that burned so swiftly through the various sections

of the county amounted to hundreds of square miles, most of them uninhabited except for

logging camp personnel. Bordering South Rogers to the north was a farm whose owner had a

large wind-driven grist mill. He decided that morning of October 15 that he would grind

grain. The strong steady wind that was blowing made it an ideal day for the job. The story

told around the countryside over the years was that he continued grinding away, in spite

of the great danger his buildings and those of his neighbors were in. His buildings caught

fire and house, barns and windmill were lost. He believed one must grind when the wind is

favorable, so stuck to his task to the last. The southeast corner of Belknap Township,

north of South Rogers and Metz, was in very grave danger. There were many farms there, as

well as the hamlet of Hagensville, all in the path of the oncoming fire. The woods of a

nearby farmer to the south were set afire in a backfire operation to reduce the impact of

the inferno coming from the southwest, and so protect the church and surrounding

countryside. All farms in the county had large woodlands that were usually connected with

others, thus giving fire a continuous pathway.

The backfiring helped as the nearest tinder had been burned in a

smaller fire. The main fire snaked its way swiftly along to the south of the area, having

been cheated of some of its prey. It went in the direction of Hagensville, then on to

Rogers and Pulawski townships, and thence to Lake Huron.

Endnotes.

When the Village of Metz vanished into oblivion, all that remained were ashes, charred

ruins and smoking rubble. The only building still standing was St. Dominic’s Catholic

church, which actually was out of town to the southwest. Additionally, the stone steps

from the Lutheran church were visible, marking where St. Peter’s once proudly stood.

By and large, the village liberty pole survived the fire as well, although the halliards

were burned off. The cocky weathervane at the top of the pole remained in working order

pointing out wind direction for whoever had a need to know.

The losses in the Metz fire were not as extensive as those in the 1871

and 1881 fires. Forty-three people died, including 15 at Nowicki’s Siding. A

conservative estimate of the damage in Metz was $60,000. Over 200,000 acres in Presque

Isle County burned at an estimated loss of over $200,000. A total of 83 families

were burned out and perhaps 1,500 people proved to be either homeless or in dire need of

food, supplies or money. While survivors searched the nearby woods and farmland for

corpses, many townsmen felt that unknown fatalities may have also occurred in deeper

forests at isolated logging camps.

After the calamity the Metz survivors wandered aimlessly about the

charred and smoking ruin. In a matter of hours they had lost their homes, farms,

implements, timber, fences, food, stock and clothing. What food was not destroyed was

sufficient for only a few days. Lumber was scarce; tools and cooking utensils, even more

scarce. The remaining horses and cattle needed hay and grain.

Relief came from all over the state. Cities in southern Michigan sent

carloads of supplies-food, clothing, stoves, furniture, blankets, hay, lumber and money.

The contributions were gathered at Alpena and transported by the Detroit and Mackinac

Railway to Metz for distribution.

Although this great disaster in Presque Isle County was named after the

town and township of Metz, which bore the brunt of it, it also raged over a vast area

covering a great deal of northeastern Michigan, and in the end, was stopped only at the

shore of mighty Lake Huron. Estimates at a later date, figured these fires destroyed about

2.5 million acres, making it one of the largest forest fires in the modern history of

Michigan.

A look back, from 1979.

More than seventy years have gone by since the tragic time of the Metz

fire. A Michigan historic site marker telling about it now stands on the Metz Town Hall

grounds. Here, before the fire, stood the schoolhouse. St. Dominic’s Church, on

Centala Road, two miles form Metz, which was spared by the fire, has since been

dismantled, and a new church has been built in the village. The Lutheran Church, which

burned with the rest of the town, was rebuilt, but the old Metz never returned.

Nowicki’s Siding is just a name held in memory because of what

took place there. Nothing remains at this once busy loading point where the Detroit &

Mackinac Railway crosses the Hagensville Road.

In 2000, crews removed the last railroad tracks from the old Detroit

and Mackinac Railroad line through town, creating a recreational trail for snowmobiles and

bicycles. The only business still operating here is the Metz Lounge, in a former hotel

that was among the first structures rebuilt after the big fire. The building's exterior

has lost a bit of siding over the years. But inside it's a friendly hometown tavern, with

an ornate tin ceiling, a pool table and a limited menu that includes huge hamburgers

favored by hunters and snowmobilers. "It's an old-time country town," says

owner Ronald Chojnacki. "If you've got a problem, people here will help you."

No one passing the site of the formerly bustling town of South Rogers,

on the corner of Metz Highway and South Rogers Road, would guess that a small village once

stood there. Never big, it did have business enough for two saloons in its heyday. Now,

though the name lingers on, it is a town without inhabitants.

Hagensville, too, is gone. Now the name is used to designate the

intersection of Highways 638 and 441, as well as the surrounding area.

LaRoque, which is adjacent to Hawks, is still a destination point on

the Detroit & Mackinac Railway, but the depot is gone, together with all buildings in

the area. Only the side tracks remain.

The 1911 Au Sable-Oscoda Fire.

Two years after Metz, the Au Sable-Oscoda fire, Michigan’s last large forest fire,

destroyed the sawmill towns of Au Sable and Oscoda. A score of lives were lost, and damage

amounted to $3 million. Coming so close, the two fires awakened public interest and

stimulated forest fire control.

Located on the sunrise side of the state, the twin towns of Au Sable

and Oscoda, like siblings vying to outdo one another, both grew at a rapid pace prior to

the disastrous fire that literally wiped Au Sable off the map. The dates was July 11,

1911. The Au Sable-Oscoda fire of 1911 delivered the fatal punch to the fast-waning

lumbering era in northeast lower Michigan. Many industries simply did not or could not

afford to rebuild. Oscoda received far less damage from the fire than her sister city, Au

Sable, but neither town rebuilt to its former stature after the fires.

Of the two communities, Au Sable was the larger. Located at the mouth

of the mighty Au Sable River, the city had a population of 10,000 residents. Prior to the

"big burn", Au Sable contained six sawmills, a sash and blind factory, three

stores, three hotels, three churches and a bank. Additionally, the Au Sable River Boom

Company was in the business of sorting and corralling logs floated down the river by the

various lumber companies. One of the town’s main interests was the Loud family mill,

a huge, sprawling complex. Never reputed to be as prosperous as Saginaw, Au Sable

and Oscoda nonetheless had had their day. When the lumber industry was at its peak, from

the 1870s through the early 1890's, the towns were already looking backward rather than

forward to their glory. Harnessing of the Au Sable River for hydroelectric power was

just beginning and Cooke Dam, the first of six installations on the river, was to open a

new era in the history of Northeastern Michigan when it began generating electricity on

February 9, 1912.

During the month of October 1908--the time of the Metz fires--a

clergyman, Bishop Williams, made his annual visit to the churches and missions in the

counties of Presque Isle, Alpena and Cheboygan. In a letter he mailed to Detroit, Bishop

Williams presciently described these sister cities three years before their demise:

I left Alpena early Wednesday morning and went down to Oscoda and Au Sable, where I spent the day. The two names stand for a shriveled, wizened, little town, formerly of ten thousand, now about two thousand, consisting of flimsy houses built of kindling wood on heaps of sawdust and sand. This is the style of most of the villages in this part of Michigan. The atmosphere was very dense with smoke. It parched your throat and bit into your eyes. If ever the fire should catch in that town, it would be burned up in five minutes, like Metz. No insurance company will take a risk here, yet the people seemed careless and confident.

The setting.

Like many villages, towns and cities at the turn of the century, the twin ports of Au

Sable and Oscoda were constructed mainly of wood-wood cut from their forests and planed at

their local mill sites--during what was still the "hey-day" of Michigan’s

lumbering industry. There were no cement sidewalks---wood chips and sawdust basically made

up the bulk of roads and walkways. They served the purpose well, keeping mud down on rainy

days and providing traction for horses’ hooves during icy winter months. No one

looked ahead and pictured these sawdust trails as prime fodder for run-away flames licking

up dry tinder.

How did this fire, considered by many to be the last spectacular blaze

of that century, start? As with the Metz and "Thumb" fires, the summer season

was extremely dry and hot. Newspaper accounts and weather statistics indicate that the

week of the fire, the Oscoda-Au Sable area was parched earth with numerous fires

reported-in Alpena, Waters, Alger, Turner, Boyne City, parts of Cheboygan and Presque Isle

counties, and other small fires in as many as ten northern Michigan counties.

The summer of 1911 was hot and dry-the front page cartoon of a Michigan

daily newspaper showed a citizen knocking on the gates of hell pleading, "I’m

looking for a cool spot." The devil answered, "Come in quickly and close the

door." The Tawas Herald reported on July 7 that "Saturday, Sunday and

part of Monday were among the warmest days known here in a long time, the mercury ranging

from 94 to 100 in the shade.

Brush fires continued to break out in the plains region of Iosco

County; some of the fires had been set intentionally to improve the following

season’s huckleberry crop. Old smoldering stumps caused smoke in the western sky.

Summary Of The Fire Situation In Michigan

With three people know dead, scores missing who may have perished,

two towns wiped off the map and nearly a dozen others reported either destroyed or greatly

damaged, Michigan is facing the worst forest fire situation the state has ever seen.

Northwest winds, said to be the worst possible for a situation of this kind, were blowing

down over the burned and burning districts of the northern portion of the lower peninsula,

spreading fires in almost every direction.

There is no rain in sight. Weather men say that a long and hot spell is

all the state can expect for several days. Without rain there is certain to be a much

larger loss of property than at present. In nearly every portion of the area affected,

families and men from lumber camps are reported missing or cut off from the outside world.

Trains are held up by walls of flame and ruined bridges.

For days, a forest fire was known to have been slowly advancing toward

Au Sable, hovering just outside the city limits, but the local populace paid little heed

to the blaze, figuring they personally had little to fear and were not in immediate

danger. But they were wrong. The winds picked up speed on the morning of July 11th,

at a reported rate of some 50 mph. The fanned flames turned this comparatively small

forest fire into a disastrous inferno. At the very same time the town began to burn, a

passing train deposited sparks along the right-of-way one mile west of Oscoda, igniting

the dry, tinder-like grass and weeds. The fire had enveloped to Au Sable and the

Northwestern Railway freight office, where a large keg of gasoline burst, spreading flames

in all directions. Finally realizing the danger, sawmills in the towns were shut

down and the men began to fight the fire...but it was too late. Most of the men quickly

ran home to look after families and possessions. The sweeping winds carried the

flames, which quickly gained momentum until, within mere moments, the fire raced across

the Au Sable River valley, leaving three-fourths of the town of Oscoda smoldering in its

wake. At this point, the twin fires joined forces and destroyed both towns. Within a scant

two hours, just 20 houses were left standing in Oscoda, while only 4 buildings remained in

the main section of Au Sable.

Source: Betty Sodders, Michigan on Fire

People fled for their lives as tongues of flame virtually licked at

their heels; docks were set afire hampering the efforts of relief vessels; trains pulled

out of town through walls of searing flame. There was little opportunity or time to

salvage personal possessions.

By some accounts the off shore winds ranged between 40 and 60 mph. Many

had fled the fire in Oscoda by crossing the river. By 7:00 pm,as the fire appeared to be

dying down, fresh winds out of the north forced the fire to cross the river and sweep into

Au Sable, firing the big Loud mill and from there to the balance of the city. The town was

leveled in a matter of minutes, Flames shot 60 feet in the air; buildings appeared to

explode and crumble, rather than burn. The fire burned so rapidly and fiercely that

few realized the actual danger until they were forced to flee for their lives. Practically

without food, clothing or shelter, the night was spent on the beach, on the sand plains or

anywhere that safety could be felt.

The ultimate death toll was never officially determined, but it is

believed to have been 5-12. For many individuals, the sand dunes along Lake Huron offered

the only surviving lifeline. Others were rescued by boats until the very docks the fire

victims were standing on caught fire. Trains managed to remove many people to safer

surroundings, such as Tawas City to the south and Alpena to the north. But generally

speaking, the majority of the population from these two affected towns were forced to wade

out into the waters of Lake Huron or the Au Sable River, where blazing sparks and bits of

burning wood and embers rained down on them.

Newspaper stories tell of the damage:

Father Of 10 Children Burned To Death On Doorstep

Remains of Two Others Picked Up on Street: Many Who Sought Safety in Boats May Have Met Their Doom

BAY CITY, Mich., July 13-The towns of Au Sable and Oscoda have been effaced from the surface of the earth. Where they once stood there is nothing.

Because of the confusion attending the rounding up of the refugees and the compiling of list of the residents, there is no way of telling how many people lost their lives. Three bodies have been found. Scores are missing and all or part of the them may have perished.

The destruction is as complete as was that of Sodom and Gomorra. Destruction more absolute than that of the twin cities of the Au Sable can not be imagined. Where stood handsome homes, churches, stores and mills, as well as in the humble sections of the city, there is nothing but ashes, bits of twisted iron and an occasional stone foundation. The image below shows the Oscoda Bank, after the fire.

Source: Betty Sodders, Michigan on Fire

Waiting For Ruins To Cool, People Plan A New Town

AU SABLE, Mich., July 14-J.H. McGillvray, secretary of the executive committee, said

this morning: "Oscoda and Au Sable will be rebuilt as one town and placed under one

government. The loss of life and property loss of residents are the only things to regret.

The city will be built up clean, with modern construction and material. All the uncouth,

unsightly shacks and ruins are gone. We have nearly 100 houses, unharmed. We have two

modern school buildings. Every industry the towns had before the fire, it will have again!

Towns And Counties Affected By 1911 Fires:

Au Sable: Wiped out.

Oscoda: Wiped out.

Millersburg: Nearly wiped out.

Onaway: Their settled portion destroyed.

Metz: Wiped out for second time in three years.

Posen: Wiped out for second time in three years.

LaRoque: Wiped out.

Tower: Reported entirely destroyed.

Alpena: Loss $500,000.

Cheboygan: Once threatened, but now safe.

Trowbridge: Threatened with destruction-part saved.

Alger: In grave danger.

Lewiston: Threatened for a time-fire under control.

Lake City: Threatened with destruction.

Ball Siding: In grave danger.

Antrim County: Fires in many places.

Oscoda County: Fire swept.

Iosco County: Fires sweeping over Michelson-partially burned.

Epilogue

The twin towns at the mouth of the Au Sable River were soon overrun by hundreds of

sightseers, who picked through the wreckage of burned out homes to find blobs of glass and

other souvenirs of the intense flames, or marveled at the immense piles of scrap iron

remaining from burned out mills. Au Sable lay completely barren for years and the

city government finally reverted back to township status. Oscoda was quickly rebuilt, but

Au Sable never recovered. Her tombstone could read: "Settled in 1850. Incorporated as

a village October 15, 1872. Moved to city status in 1889. Burned July 11, 1911. Died

officially in 1920. Buried in 1929."

The fires---both the major fires described above and the many others that swept through Michigan (an almost annual occurrence in logging counties)---did not bring an end to human habitation there. Agriculture, especially livestock raising and diary farming, which grew in importance as logging died, today leads the economies of many former white pine-rich areas. Missaukee and Kalkaska Counties, for example, also have flourishing Christmas tree industries and are well-known for their recreational resources. The latter occur primarily on public land, left behind by loggers and lumber barons who had no more use for this land.

Note: some of the text and images in this section have been paraphrased and taken from Betty Sodders' book, "Michigan on Fire", and from various issues of Michigan History magazine. Finally, parts of the text above have been paraphrased from C.M. Davis’ Readings in the Geography of Michigan (1964).

This material has been compiled for educational use only, and may not be reproduced without permission. One copy may be printed for personal use. Please contact Randall Schaetzl (soils@msu.edu) for more information or permissions.