KARST COUNTRY OF THE NE LOWER PENINSULA

A unique landscape can be found in the Northeastern Lower Peninsula of

Michigan about fifteen miles north of Atlanta in southwestern Presque Isle County. Here

are located sinkholes, also known as sinks or swallow holes, because they

"swallow" streams. The bedrock underlying this general area is limestone, which

dissolves in weak acids, such as those in rainwater. Sinkholes are formed when large

circular caves in the limestone collapse. The small group of sinkholes in NE Lower

Michigan is only part of a larger karst system extending eastward to Lake Huron. Karst

refers to a limestone region with many sinkholes, abrupt ridges, caverns, and disappearing

and underground streams. Some sinks, like Shoepac Lake, are filled with water while others

are dry. The bottom of the first sinkhole, just east of Shoepac Lake, is more than 100

feet lower than the surface of the lake, an unusual occurrence.

The karst in Michigan lacks sufficient water pressure to flush out the

overwhelming load of sand, clay and broken rocks from 100-140 feet of glacial overburden

which collapsed into the system sometime after the last glacier left the area. Most of the

sinks are round, approximately 80 to 100 feet deep, and have walls sloping up to 850. The

bedrock extends down several hundred more feet to the top of a shale layer, which has

likewise collapsed along with other formations to a depth of 900 feet.

The Michigan basin contains limestone and evaporite rocks, which are soluble in weak acids. In NE lower

Michigan, Devonian limestones of the Traverse Formation are exposed, as at the calcite

Quarry in Rogers City. Infiltrating rainwater and snowmelt, which picks up weak carbonic

acid from its short-term contact with the carbon dioxide in the air, has dissolved some of

these rocks, at preferred sites. The dissolved rocks may collapse to form sinkholes, or

the solution cavities may remain open, as caves.

The presence of karst and karst lakes in northeastern lower Michigan has been known

since early surveys of the state, and has been documented by several technical and popular

authors. Sinkholes, sinks, or dolines are areas where surface water can easily

infiltrate to the groundwater, and can do so very rapidly with very little

"filtering" by soils and overlying rocks. Thus, sinks represent

"highways" of rapid transit of water from the surface to the subsurface. Sinks

are, therefore, areas of great concern for they represent sites of potential contamination

of groundwater, from non-point source (such as fertilizers) and point-source (such as

cattle yards) pollutants.

Types of Sinkhole Lakes

Many lakes in northeastern lower Michigan developed in conjunction with sinkholes and

other ground water solution features. There appear to be three types of karst lakes in

northeastern lower Michigan: sinkhole lakes, sinkhole-controlled lakes, and solution

lakes.

Sinkhole lakes are generally round in shape and cover

geographically-small areas. The small lakes in northeastern Otsego County, the small

intermittent lakes near Shoepac Lake of Presque Isle County, and small lakes near Leer of

Alpena County fall into this category.

Rainy Lake and Sunken Lake are sinkhole-controlled lakes, and are

characterized by sinkholes in the lake basins which control the lake level. These lakes

also have surface inlets and outlets such as streams that enter and leave the lake.

The third type of karst lake are solution lakes, which develop along

linear ground water solution features in soluble bedrock. Devil’s Lake, north of

Alpena, is a solution lake, as are Trapp, Mindock Fitzgerald, and Long Lakes in northern

Alpena and southern Presque Isle Counties. Some solution lakes may also be

sinkhole-controlled lakes, such as Devil’s Lake, which occasionally drains through a

sinkhole rather than through Long Lake Creek, the surface outlet.

There are many linear features and crevasses throughout this area which

are not associated with lakes. Some of these appear as bedrock cracks which can be less

than 10 to over 100 feet in depth. These features are common around Devil’s, Trapp,

Mindock, and Fitzgerald Lakes. Some of them are parallel to the regional strike of the

bedrock formations, and some are parallel to the trend of fracture intersections.

As can be seen here, collapse of a sink is also a localized natural hazard!

The Stevens Twin Sinks Preserve is a 30 acre parcel owned by the Michigan Karst

Conservancy in Alpena County. It was purchased in 1993 with gifts from William and Archie

Stevens and other members and friends of the MKC. The Preserve surrounds two sinkholes

separated by a fragile saddle-ridge, each about 200 feet in diameter and 85 feet deep,

which give the Preserve its "twin sinks" name. An interpretive nature trail that

visits the rims of these sinkholes and other karst and natural features of interest is

currently being developed.

Other sinkholes in the area are on private property and may not be visited by the public.

The Stevens Twin Sinks Preserve is the only sinkhole site open to the public in this area.

All nature lovers trust that the public will treat the sinkholes and other features to

help preserve them for public interest and enjoyment now and in the future.

Quite recently the Bruski Sink across Leer Road (photo below) was donated to the

Conservancy and made part of the Preserve. This sinkhole has been used for illegal dumping

of trash for many years, contributing to the contamination of groundwater in the area. The

MKC plans to clean out most of the visible trash and install barriers to future dumping.

In NE lower Michigan is an area of concentrated sinkholes,

specifically in eastern Alpena and Presque Isle Counties. Many are in county parks or, as

seen here, preserved for future study. Alpena and Presque Isle counties are

underlain by a thick sequence of Devonian limestones and some shales, called the Traverse

Group. At a depth of ca. 800 feet at the Preserve occurs the Detroit River Group, which

includes considerable evaporites - anhydrite and gypsum. These dissolve much more readily

than limestones and have been totally removed further north by water circulating at depth.

The sinkholes of the area are created by collapse of Traverse Group rocks into the

cavities created by the dissolving of Detroit River Group evaporites. The result is the

settling and collapse of large rock blocks with some shattering, leading to a hummocky

terrain, such as can be seen in and to the east of the Preserve. Also present on the

Preserve are "earth cracks", resulting from the slumping of the rocks .

The water that dissolved the evaporites found its way underground along

joints and especially joint intersections. These points of greatest water input created

the earliest and largest voids in the Detroit River rocks, which allowed the rocks above

to collapse - all the way to the surface, to form the sinkholes visible today. They tend

to be aligned along joint trends, as indicated by the grouping of the Twin and Bruski

sinkholes.

Evidence for the dissolving of the evaporites is found where the water that goes

underground in the sinkholes returns to the surface - from submerged sinkholes in Lake

Huron, twenty miles to the east. The resurgent water is saturated with gypsum.

This area of Michigan was glaciated and a considerable amount of

glacial outwash - sand and gravel - mantles the limestone, which can be seen from the

parking area. That the sinkholes are not also filled with outwash shows that they

increased in depth following the melting of the glaciers (it is not known what depth of

glacial outwash fills the bottom of the sinkholes). The exact relations between the

glacial deposits and the sinkhole formation have not been elucidated yet and is an area

for future research.

Unfortunately, ignorance of how these sinks formed, and their links to

groundwater, facilitated past uses of them as dumps. Shown above is the Bruski Sink

located near Posen, which had been used as a dump/landfill for years. Still other sinks in

the area are located downslope from cattle yards, and pose a different (and ongoing)

threat to groundwater quality.

Shoepac Lake

Silt and clay brought in by small streams have thoroughly

sealed the bottom of some sinkholes, thereby creating sink lakes. Shoepac, and several

nearby lakes, is made up of one or more sinkholes completely sealed off from underground

drainage. Recent, 1976 and 1994, active karst collapse can be seen at the eastern edge of

Shoepac Lake, providing evidence of the ongoing collapse of the sinkholes beneath the

lake.

Sunken Lake and "Mystery Valley"

Legends concerning Sunken and Rainy Lakes have been written about since the 1950's. An

early geologist, Newton Winchell, speculated on the presence of an underground drainage

system in Alpena and Presque Isle Counties. Early State Geologists, such as Carl Rominger

and R.A. Smith also observed the sinkholes and karst features of this area.

Sunken Lake and its dry-lakebed counterpart, "Mystery

Valley", are located in sections 32 and 33 of Presque Isle County, just north of the

Alpena-Presque Isle County line, and 2 or 3 miles north of the well-known Leer sinkholes.

Sunken Lake is located on the North Branch of the Thunder Bay River. In the 1950's, the

Michigan Tourist Council reported that flowers were planted in the floor of Mystery Valley

after Sunken Lake has dried up and disappeared one year. During the following year, the

lake reappeared as the sinkholes in its bed again became plugged, illustrating how and why

these types of lakes drain--they have sediment-plugged sinkholes in their beds that

occasionally become "unplugged" of sediment, allowing the water to flush down

the sinkhole into subterranean drainageways in the fractured limestone below.

One year during the early 1900's, it is alleged that lumberers

attempted to float logs down the North Branch of the Thunder Bay River at Mystery Valley,

but the logs would stop at the large sinkhole in the valley. Since the log jams caused the

water which normally flows into the sinkhole to back up, the valley flooded and a

diversion dam was consequently built to route the logs away from and around the sinkhole

at Sunken Lake. Another popular legend from the lumbering era states that loggers would

"ride into the sinkholes" on their logs, then reappear in Misery Bay of Lake

Huron, 23 miles to the southeast, "still smoking their pipes".

The Rainy Lake Episode(s)

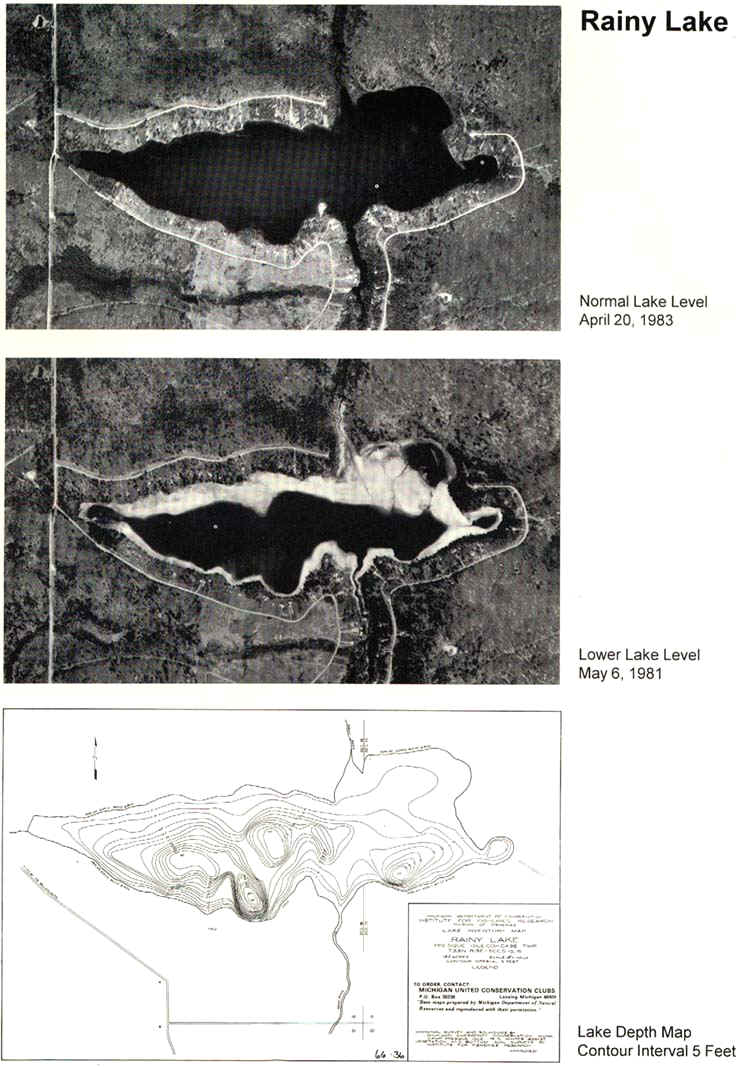

Rainy Lake, located about four miles east of Shoepac Lake, is

composed of five or six sinkholes. The deepest sink typically has up to 100 feet of water

in it and acts as a swallow. Rainy Lake has had significant fluctuations of its water

level in the past. This is frequently caused by catastrophic drainage due to the temporary

loss of the silt and clay "plugs" which seal the sinkholes. The last drop

occurred between 1979 and 1982 (compare the aerial photos of Rainy Lake taken in 1981 and

1983), when a 4 to 5 foot vertical drop in the water level occurred in February 1982.

Measurements have shown a change in the bottom contours of the lake due to the continuing

collapse of sinkholes beneath the lake.

Although Sunken Lake has disappeared and reappeared several

times, historical documentation is more complete for Rainy Lake. Rainy Lake is a

rather large lake in SW Presque Isle County (see below). This lake, more than a mile

in length, is underlain by limestone bedrock, which is obviously full of solution holes,

caves, and joints.

It is well-documented that Rainy Lake drained in 1894, 1925, 1950, and in 1980. By

1983, Rainy Lake has fully recovered from the 1980 drainage event. There are at least five

sinkholes in the bed of Rainy Lake, which reportedly drain into a west-east trending

subterranean drainage system. In the 1980 event, however, only one sinkhole appeared to be

active.

This subterranean drainage system is reportedly connected to Sunken Lake, Shoepac Lake,

Devil’s Lake, and Misery Bay. No one has seen or explored this alleged underground

drainageway, but geological evidence supports its presence. According to Will Gregg,

during the 1925 event, citizens expected to find dead trout in the dry lake bed, since

Rainy Lake is normally a productive trout lake. Much to their surprise, no dead fish were

found, yet the following year, when the lake reappeared, the trout also came back.

Obviously, the fish had been swept into the subterranean passageways with the water, only

to reappear with the water at a later point. In the same account, a story is told of

another early attempt to float lumber down the Rainy River. Immediately prior to the log

run, the lake drained through the sinkholes. The lumberers consequently built a rail line

on the dry lake bed. After the logs were shipped, the Rainy Lake sinkholes again became

plugged, and the lake reappeared.

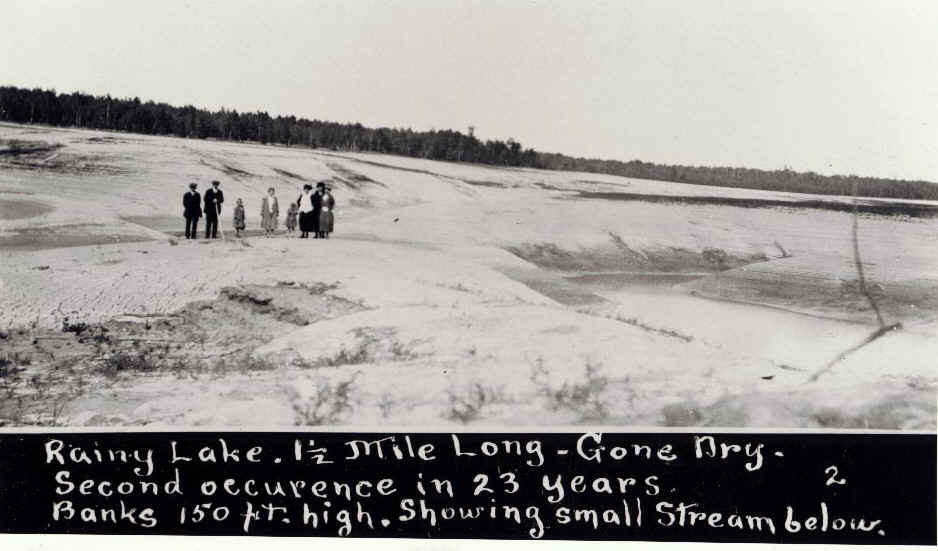

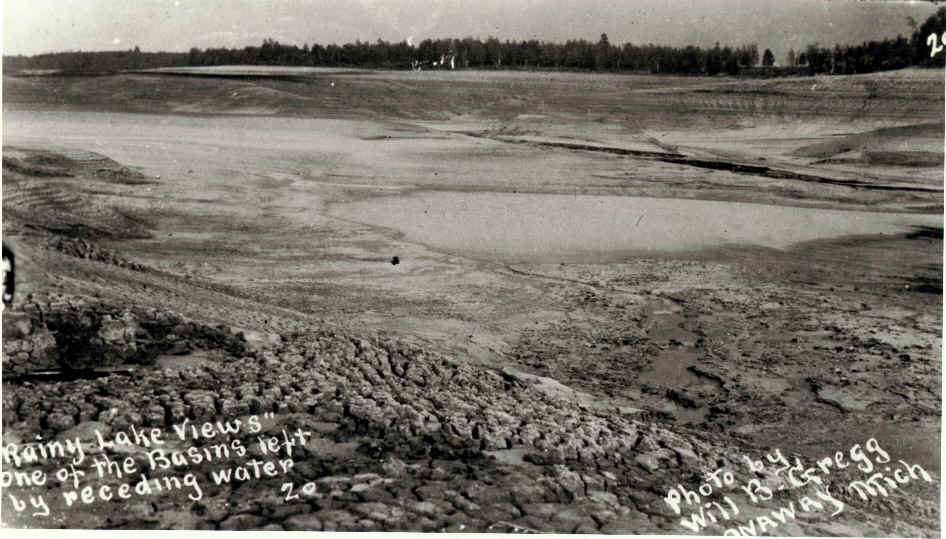

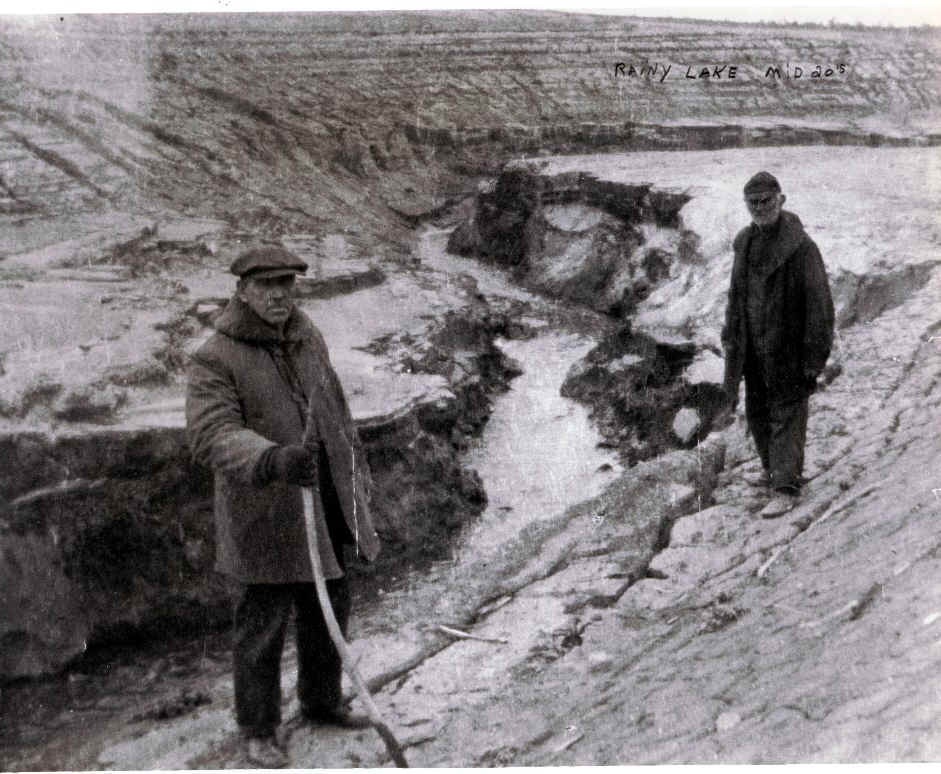

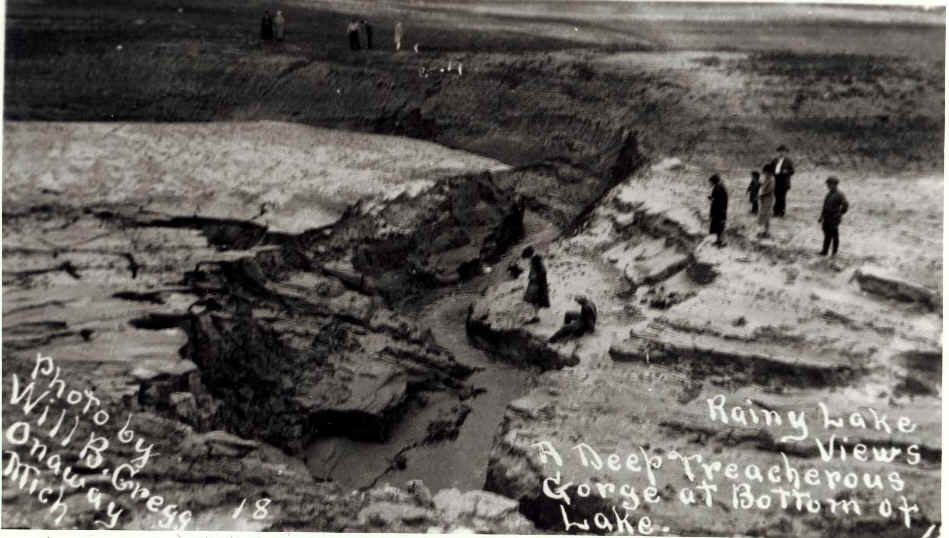

The images below are from a personal collection, and have been reprinted here. The

depict conditions on the dry lakebed of Rainy Lake during the 1925 event.

Note, in the images below, how the waters have cut a gorge into the soft mud of the

lakebed, as they rushed out of the lake.

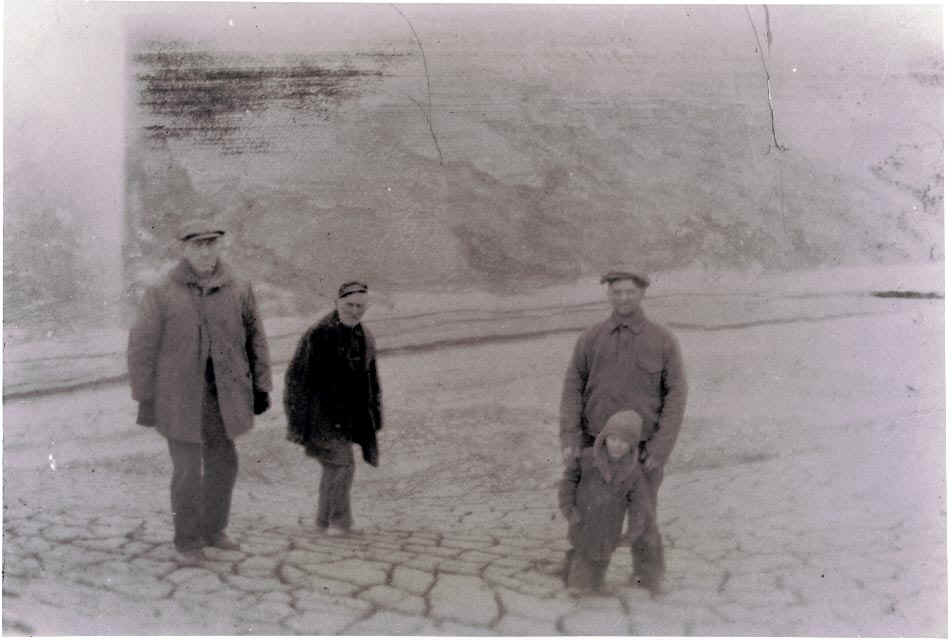

More images, this time with an annotation:

The image above is of the dried clays on the bed of Rainy Lake. The caption

handwritten on the back of this picture said: "The small boy is me, Albert

Tennant with my father Del Tennant, at my back and to his right is George Tennant my

grandfather and to his right is A.C. Robinson my other grandfather. Note the cracks in the

clay bottom. My father has told me that some of those cracks you could put your arm full

length in, and that some places you could hear a roar like an under ground current."

Rainy and Sunken Lakes remained geological curiosities for many years. In the late

1960's and 1970's, however, citizens began buying lots on Rainy Lake in several

subdivisions. It was an ideal location for a summer cottage until late 1980, when the

sinkholes in the bed of Rainy Lake again became unplugged and the lake began draining,

after a period of time when the lake was higher than normal. In 1982, the level of Rainy

Lake had dropped over 45 feet, and the shoreline had receded over 500 meters in places.

During the 1980-1982 incident, water in Rainy Lake was draining at an estimated rate of 10

gallons per second.

A significant number of cottages and summer homes were built around

Rainy Lake between the times of the 1950 and 1980 incidents. The residents were

understandably concerned, and after a 30-year dormancy, interest in Rainy Lake was again

revived. In an attempt to help bring the lake level up, the Michigan DNR opened a stop-log

wildlife flooding dam in 1982 and allowed water to flow approximately six miles down the

Rainy River into Rainy Lake. As expected, the resulting increase in lake level was of

small magnitude, and only temporary. Rainy Lake has now stabilized, and it is back at its

normal level. Late in 1982, the major sinkhole through which the lake drained once again

became naturally plugged, allowing the lake to fill.

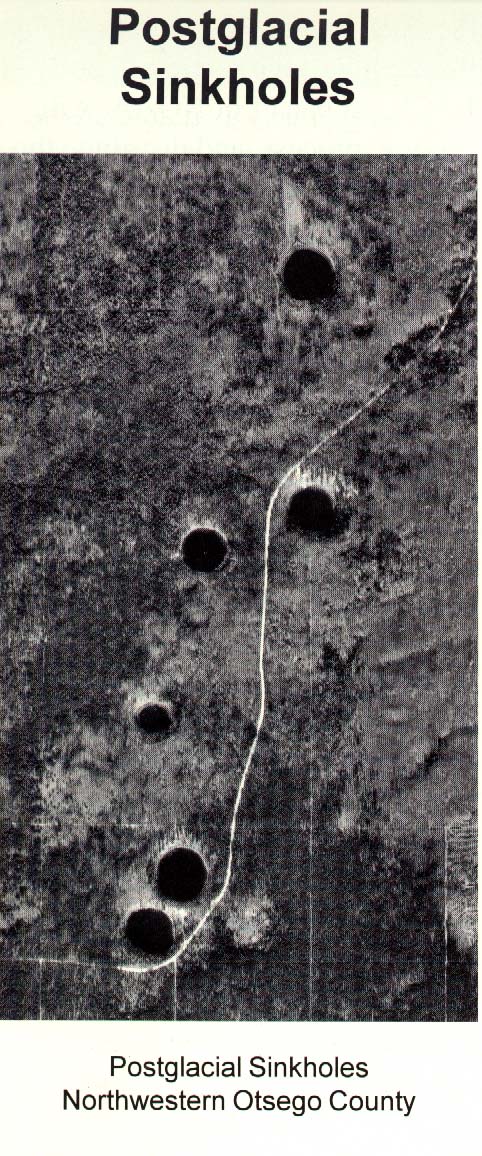

Post-glacial sinkholes

Postglacial sinkholes are likewise a unique feature of the karst landscape.

These sinks are typically nearly perfectly round, about 400 to 500 feet in diameter, with

a depth up to 100 feet. Postglacial sinks look very similar to kettle holes with which

they are often confused by the untrained eye (sinks are about 5 degrees steeper and are

VERY round).

KARST IN ALPENA AND PRESQUE ISLE COUNTIES

Very little work has been completed on the relation of karst in northeastern lower

Michigan to the structure of the Michigan Basin, prior to the work currently in progress.

Basic structural and tectonic processes in the Michigan Basin were reviewed, and almost

500 lineaments in northern Alpena and southern Presque Isle Counties which are discernible

on aerial photographs, were mapped. Two predominant average azimuth orientations of

photolinears were calculated.

Many of the linear features discernible in northeastern lower Michigan

developed at least in part by ground water solution processes. The primary development of

fractures probably took place concurrently with the uplift of the Michigan Basin at the

close of the Paleozoic Era. Many of the northwest-southeast and northeast-southwest

trending sets of lineaments developed along fracture intersections. Although evidence

exists for an upper Devonian karst system, much of the post-Paleozoic karst appears to be

oriented along the northwest-southeast linear trend, which is roughly parallel to the

regional strike of the bedrock in the area. Much of the subsurface ground water movement

in this area probably follows linear zones of weakness which developed along fracture

intersections.

Much has yet to be learned about karst phenomena in northeastern lower

Michigan, and what controls the seemingly periodic cycle of lake lowering due to karst,

such as has happened at Rainy Lake. Modern technology will not prevent karst lakes from

draining in the future, but much insight is to be gained so we can better predict cyclical

trends in karst phenomena and be better prepared to deal with them as they develop.

The work of the Michigan Karst Conservancy

is carried out by volunteers, who believe in the value to the public of protecting

examples of karst features in Michigan for education and scientific uses. Donations to the

MKC are tax deductible in accord with federal law. For further information about MKC, and

membership in it, write:

Michigan Karst Conservancy, 2805 Gladstone Avenue, Ann Arbor, MI 48104-6432.

(e-mail: mkc@cyberspace.org)

Much thanks to Dennis Hudson and the MSU Center for Remote Sensing and GIS, who supplied some of the text and imagery for this page.

This material has been compiled for educational use only, and may not be reproduced without permission. One copy may be printed for personal use. Please contact Randall Schaetzl (soils@msu.edu) for more information or permissions.