SAND AND SAND MINING

Part II

SAND MINING ECONOMICS

Both mineral and sand mining industries have been on the Michigan scene for over a

century. Table 1 provides a further breakdown of the production and value of sand for

industrial uses.

Table 1 - Production and use of industrial sand in Michigan in 1973

| Uses of the sand | Production (tons) | Value ($) |

| Molding | 4,466,000 | 10,402,000 |

| Glass | 535,000 | 2,018,000 |

| Traction | 295,000 | 710,000 |

| Other (scouring powder, furnace sand, and hydrofacing sand) | 433,000 | 1,087,000 |

| Total | 5,729,000 | 14,217,000 |

Historically and economically, those industries concerned with specific

mineral utilization are located near a minable source of supply of that mineral. The

foundry industry, which is dependent upon several mineral commodities, originally followed

the coal or lumbering industry for its energy needs. Another consideration for bulk

mineral users was proximity to cheap water transportation. Raw materials not found at the

site could be imported by water at a better competitive price while at the same time a

more economical way to ship bulky finished products was at hand. Limestone and clay for

foundry use were often secured locally and brought in by truck or railroad.

As the foundry industry evolved over time, its associated technology

placed more stringent requirements on the quality of sand used in its metal casting

processes. Early foundry sands often were imported from southeastern Ohio. During the late

1910's and early 1920's, larger and larger quantities of dune sand began to be used in

Michigan’s foundry industry as machines replaced manual labor and industrial

expansion continued apace. New metal casting processes required a higher quality sand. At

this time, it was found that some Michigan sands could not only withstand the extreme

temperatures needed for pouring molten steel but were also more durable, cheaper to mine,

and required little or no treatment prior to use in the casting process. Sand with these

same characteristics is also preferred by the glassmaking and other minor sand dependent

enterprises.

MINING, PROCESSING, AND RECLAMATION

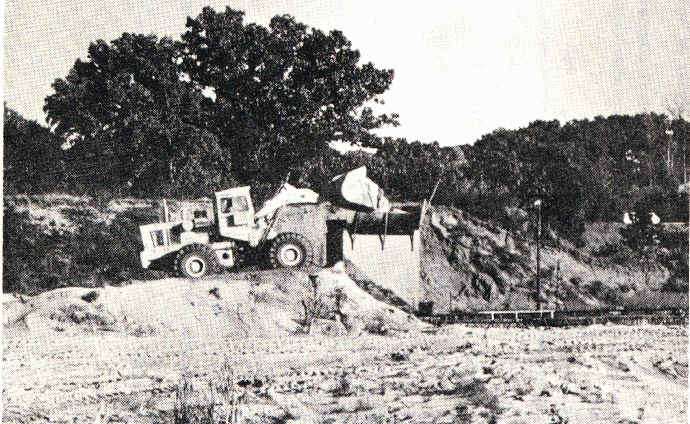

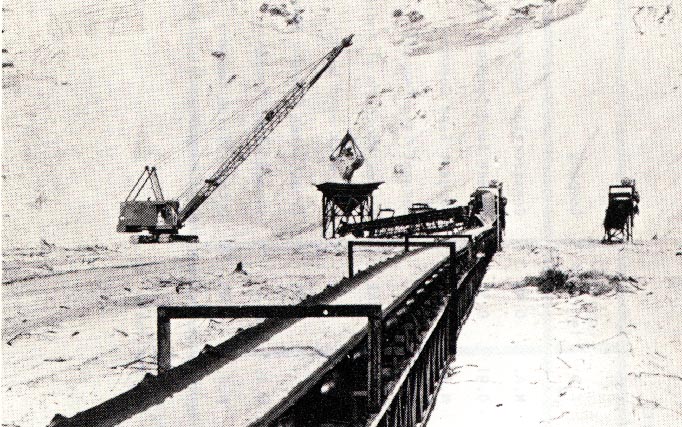

Surface mining is the most common method of sand extraction. In this process, a front-end

loader (see below) or crane with a clam shell (also below) is used to move sand . Sand is

removed from the dune and loaded directly into a hopper where it is rough screened. After

screening it is either loaded into trucks or onto conveyor belts and transported to a

storage stockpile.

Source: J Lewis,

Michigan

Geological Survey Division Circular (#11), 1975

Source: J Lewis, Michigan Geological Survey Division Circular (#11), 1975

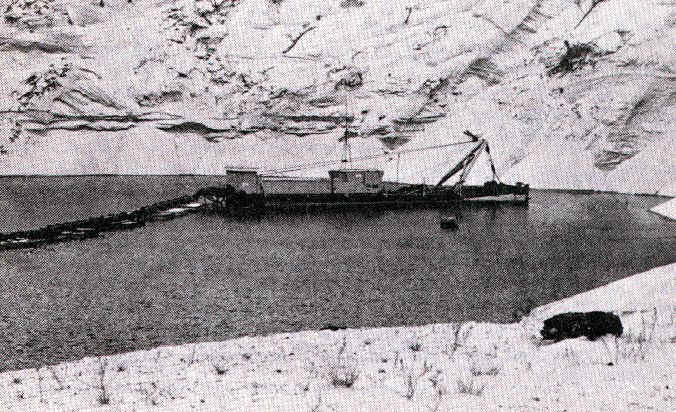

The dredging method of sand mining (see below) is somewhat more costly

and requires more elaborate equipment. The principle of this operation is to jet water

under high pressure against the dune bank or pond bottom making a sand slurry. This slurry

of riled sand is then sucked up by another pipeline and transported to a surge tank or

storage pile. The water transporting the sand is recovered and returned to the pond. A

dredge can mine sand to a depth of 20 m below the water surface.

Source: J Lewis,

Michigan

Geological Survey Division Circular (#11), 1975

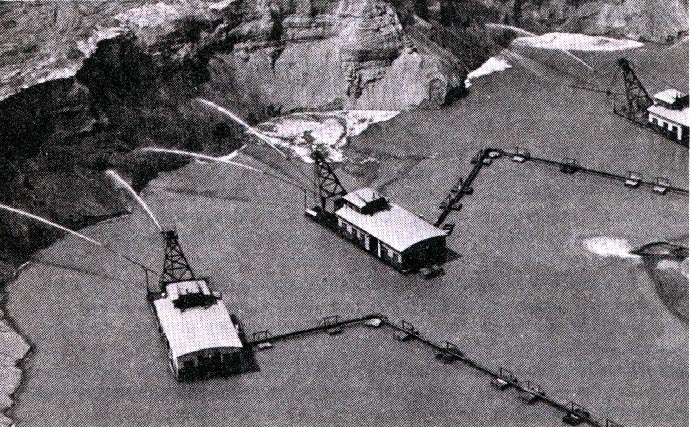

Hydraulic mining is very similar to dredging except the operation is

conducted from a portable stand rather than from a dredge. Water is ejected under several

hundred pounds pressure from a swivel nozzle which is mounted on the stand. The

pressurized water stream is aimed at a dune bank, washing it down into a small holding

pond (see below). From this point, the sand is pumped through a pipeline to a surge pile.

Once the sand slurry reaches the surge pile, the water is drained off and recycled back

through the high-pressure water line to be used again.

Source: J Lewis, Michigan Geological Survey Division Circular (#11), 1975

Unlike sand, loosely cemented sandstone usually requires drilling and

blasting before it can be mined. After overlying soil and unwanted rock have been removed

holes are drilled and explosive charges are placed in them and detonated. The rock is

broken into pieces that are small enough to be handled by front-end loaders. These pieces

are loaded into trucks and transported to the plant for crushing and screening.

NEEDS OF THE SAND MINING INDUSTRY

Industrial quality sand must meet certain prescribed chemical and physical properties,

must be located near its market, and must be mined, processed and shipped economically.

From the industrial viewpoint, location of proven sand

resources relatively near to market or to transportation facilities is second in

importance only to the quality of the sand deposit. Because the sand must be transported

to the market, transportation costs are an important economic factor. The heavy (sand)

product needs to be transported at minimal cost. Long distance hauling cost is minimized

by ship and rail transportation. Shorter haulage is usually provided by truck and is,

hence, more expensive. In many cases, transportation charges are several times more costly

than the value of the sand itself.

In addition to location, sand must be available

in sufficient quantities to assure its long-term availability to the industry.

Availability of the resource must also be coupled with reasonable access to the resource

itself. Public or private land ownership and local regulations, for example, all affect

the industry’s capability of mining sand resources.

Mining costs are another important

consideration of the industry. The more expensive the extraction process the greater the

cost that must be passed on to the consumer of the final product. Included in the cost of

mining are blasting, removal of overlying rock and soil (overburden), mechanization, and

reclamation of the mined area.

The last major consideration of the sand mining industry is ore processing costs. Processing costs, like mining costs, must be

kept as low as possible. The final product – industrial sand – must be nearly

free from deleterious or undesirable minerals. Added treatment costs to remove unwanted

material such as roots and rocks, increases the market price accordingly. Both the foundry

and glassmaking industries must adhere to stringent physical and chemical sand

specifications. Changes in processing techniques utilizing less desirable types of sand

would require changes in technology with an attendant increase in cost.

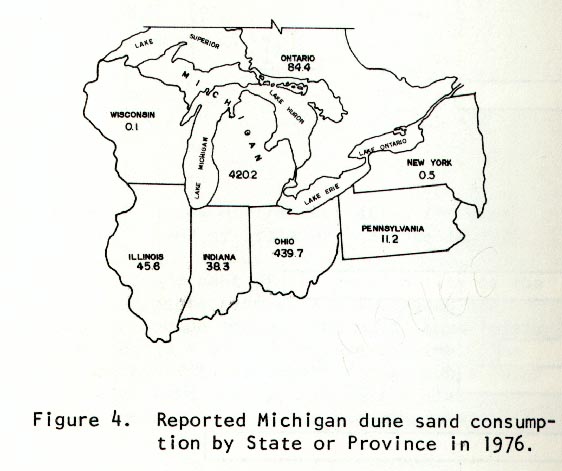

In terms of the industry’s economic impact, a 1975 newspaper

article stated that there are 1,334 foundries employing 144,000 people that use sand from

the Lake Michigan area. The foundry business, which depends upon sand for making cores and

molds, is the one of the 20 largest industries in the USA, in terms of goods and services

produced.

Source: J Lewis,

Michigan

Geological Survey Division Circular (#11), 1975

SAND MINING AND THE ENVIRONMENT

The Lake Michigan Federation, a Muskegon-based environmental group, has

been actively involved in the fight to save Michigan’s sand dunes for the past six

years. In 1976 there were 15 active mining sites covering 3,228 acres. By 1999 that number

had grown to 4,848 acres at 20 sites. About 46.5 million tons of sand have been removed

since the passage of the dune protection act. The sand is used for making car molds,

trains and airplane parts. The sand along the shore is useful to the auto industry because

of its composition. It is unique in its purity. Quartz is the primary ingredient.

The depletion of the dunes also has negatively affected wildlife, such

as the Piping Plover bird, which is on the federal endangered species list. Only 23 Piping

Plover nests were accounted for in Michigan in 1996, many of which nest in the dunes.

CONCLUSIONS

Michigan’s industrial sand mining industry faces an uncertain future. This industry,

like many other extractive industries, is being subjected to increasing public and

governmental pressure to severely limit or stop its sand mining operations, especially

along Lake Michigan’s shoreline areas.

Dune sand is preferred by industrial consumers because of its chemical

and physical properties, ready availability, and agreeable price. Sand mining operators

prefer to quarry dune sand (below) because it is found in large volumes and is relatively

free from excessive contamination and overburden. Compared to other sand sources it

requires less processing, is more easily mined, and is close to bulk transportation

facilities. The mining of thinner, inland sand deposits usually require additional

processing, more handling, and disturbs large areas. The additional consumption of time

and energy to carry out all of these operations contributes to increased costs.

With the increased concern about sand mining in Michigan we are now

forced to make a decision: 1) Should all dune sand mining be halted along the Great Lakes

shorelands; 2) Should dune sand mining be allowed to continue unabated as in the past; or

3) Should we seek a compromise to these opposing positions?

The elimination of sand mining within the Great Lakes shorelands, is

supported by growing numbers of ecologically minded citizens. They contend that the dunes

and their fragile ecosystems should not be destroyed as they are vital to the ecology of

the area and invaluable educational and recreational assets that should be preserved

intact for future generations to study and enjoy.

The continuation of present mining practices is supported by equally

concerned industrial opponents. They contend that Michigan is an industrial state and that

industrial sand is the backbone of all basic industrial manufacturing in the state.

Without dune sand our automotive and associated manufacturing industries would be forced

to shut down or seek more costly alternatives.

Much of the text and imagery on this page is from a 1975 Michigan Geological Survey Division Circular (#11), by J. Lewis.

This material has been compiled for educational use only, and may not be reproduced without permission. One copy may be printed for personal use. Please contact Randall Schaetzl (soils@msu.edu) for more information or permissions.