OTHER FOREST PRODUCTS

Back in 1935 and 1940, forest economists, armed with the first complete inventory of the

UP forests, predicted an almost total decline of forest industries in this area. It just

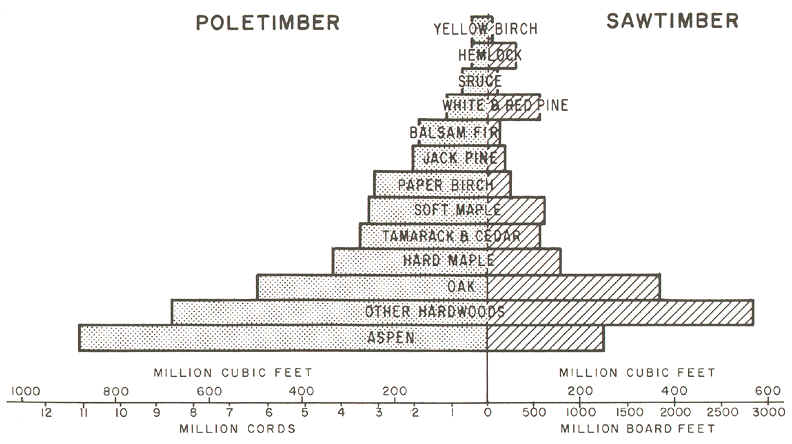

didn’t happen! Small sawmills replaced the old, obsolete large mills, and pulpwood demand shifted in emphasis from spruce and fir to aspen,

which had previously been considered to be a worthless "weed tree".

Besides the jobs and wages produced getting forest products to the

industries that needed them, at manufacturing plants such as sawmills, veneer mills, box

plants, flooring mills, cedar fence plants, pulp and paper mills, and others not including

furniture industries, the value added to forest products through manufacture amounted to

millions of dollars per year. This represents many more people employed in these

industries, and the "value added" is more wages, services, taxes, equipment, and

utilities, all of which is additional income. Such items as storage, handling,

advertising, sales costs, and transportation of finished products are more difficult to

assess, but do generate considerable volumes of income to add to this total.

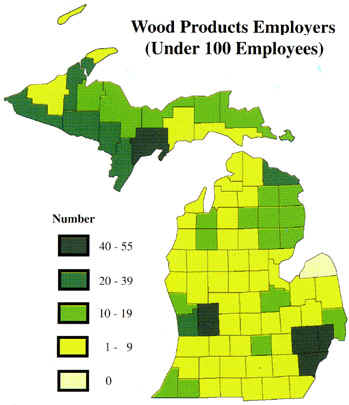

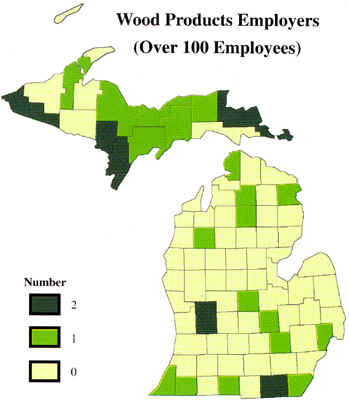

Few people realize the varied nature and numbers of industries

dependent on the forests for raw materials. Much more important, of course, are the many

workers employed and the income they receive.

Source: Unknown

The "placemat" maps (above) were produced by the Michigan Geographic Alliance and the Science/Mathematics/Technology Center, Central Michigan University, with funding from the U.S. Dept. of Education. For further information email Wayne.E.Kiefer@cmich.edu

Maple Syrup

Michigan ranks sixth in the nation in maple syrup production (there are ten major

producing states), with an estimated 88,000 gallons of production in 1996 and 73,000

gallons of maple syrup in 1999. Average price received per gallon (in 1993) was

$27.20, compared to $25.50 in 1992.

Vermont is America's leading producer. The collection of sap begins in early spring each

year, when the days begin to warm

but temperatures still dip below freezing at night. The trees must be at least 10 inches

in diameter to be tapped, and as the tree grows, more taps are added.

It takes approximately 40 gallons of sap to produce one gallon of

syrup. The excess water is boiled off in order to concentrate the sugars. A container of

maple syrup can be stored on the shelf until it is ready to be used, but once it is

opened, it should be stored in the refrigerator.

Due to the great increases in charcoal use for picnics, camping, and

home barbecues, the volumes of wood used for this product has increased appreciably during

recent years. Michigan is one of the nation’s largest charcoal producing states. We

also produce an important amount of chips, slabwood, and veneer cores which would

otherwise be wasted by other wood using industries. As a benefit to the forests, these

industries are extremely important, being a market for the unsound, crooked, or

poor-quality trees which need to be removed, but are wanted by no one else. Elimination of

such material from the forests is one of the basic steps in good management.

These are the most important primary wood-using industries, but there

are many more, such as utility poles, piling, railroad ties, mining timbers, excelsior

wood (to Wisconsin), and large quantities of fuelwood, all of which create jobs, require

equipment, and product wages and saleable products. They all use wood cut from the

forests.

Cedar products

In many parts of Michigan vast acreages of cedar swamps exist. These swamps provide

raw materials such as cedar logs (for "log cabins", fence posts (cedar fence

posts decay very slowly, and thus are very much in demand), and cedar bark for landscaping

and mulch. Because cedar swamps are wet places, much of the logging must be done in

winter, when the soils are frozen and beneath a snowpack.

Veneer

Wood veneer extremely thin sheet of rich-coloured wood (such as mahogany, ebony, oak, or

rosewood) cut in thin sheets and applied to the surface area of a piece of lower quality

wood. There are two main types of veneering, the simplest being that in which a

single sheet, chosen for its interesting grain (yew or purple wood, for example), is

applied to a whole surface of inferior wood in one unit. In the more complex variation

called crossbanding, small pieces of veneer wood are fitted together within a surrounding

framework in such a way that the grain changes pattern, thus altering the tone according

to the light. This process can produce complex fan shapes, sunbursts, and floral patterns.

When the veneers are made up of small pieces cut from the same larger piece of wood and

affixed so that their grain runs in opposite directions in accordance with a formal

geometric

pattern, the process is known as parquetry.

Veneering allows the use of beautiful woods that because of limited availability, small

size, or difficulty in working cannot be used in solid form for making furniture. In

addition, it significantly increases the strength of the wood by backing it with a

sturdier wood and, through the process of laminating veneers at right angles in successive

layers, offsets the cross-grain weakness of the wood. Michigan is a large producer

of veneer woods, especially oak and birdseye maple.

Source: Unknown

Secondary Forest Products

Sawlogs, pulpwood, and firewood is cut in forests, and in so doing creates many

jobs in the primary wood-using industry. Next comes the secondary industries

which use the lumber, the pulp, or the paper for further manufacture into products for the

ultimate consumer. There are flooring mills, crate mills, box and pallet plants, furniture

and fixture plants, and many more, including a few paper and paper products plants.

In this secondary phase, the wood-using industries employ at least

twice as many people as have been employed up to this point, and pay wages, taxes,

utilities, services, and add the largest part to the total income which comes to Michigan

from its forests. There are so many items of equipment and wages involved along the way,

and so much manufacturing, that neither time nor space permit a full accounting. Suffice

it to say that there are chain-saws (gas and oil for them, too), axes, wedges, chains,

tractors, trucks, cranes, hoists, steel cable, gloves, clothing, groceries, autos to carry

people to and from work, homes, haircuts, fishing tackle, beer, guns, newspapers, iodine,

and bandages, all paid for by this work.

These people help support the schools, roads, and local government.

And, speaking of roads, it should be pointed out that on an average, one mile of woods

road must be constructed for hauling each 1,200 cords of pulpwood cut, or 600 thousand

board feet of logs. This results in the construction of many miles of roads usable by

hunters, berry-pickers, fishermen, and campers, none of whom could have brought in the

needed gravel fill, built the small bridges, or installed the necessary culverts! These

forest visitors in pursuit of recreation also spend large volumes of money in the areas

which they frequent.

Fortunately, these "working forests" from which such wealth

of income is derived also produce more animals and birds, provide continuous changes in

the scenery, favor the production of many flowers and berries, and do an excellent job of

water conservation, maintaining relatively stable flow and even temperatures in the trout

streams. Without use of the products, these benefits would be lessened, and without the

work and wages, many less people would be able to enjoy them.

Here's an interesting story about one gentleman who bought some wooded land in Michigan

and got "more than he'd bargained for".

The asking price for the woodlot at that time, about 1963, was $1,700.

My advisor/friend, Charlie Peterson told me to buy it, so I did. Soon after I sold just

the elm trees on the woodlot to the Michigan Maple Block Company in Petoskey who make

hardwood butcher blocks of all kinds. They looked it over and paid me $1,700 for the elm.

Dutch elm disease was just starting, so this was a good move. A few years later I sold the

maple and basswood trees for $8,000. So you see, in many ways, money does grow on

trees. After this, we had other timber sales from the woodlot, usually with the aid of a

registered forester.

Then we clear-cut the aspen (formerly thought of as a weed tree and now

the most important ingredient in particle board), which went into chips for plywood.

Chipping eats up everything from the trunk to the tip, including branches, needles and

all, leaving the forest floor clean. This operation lasted two years and consisted of

whole trees being cut, skidded and run through a chipper on the site, then hauled by big

trucks to the mill.

Our latest timber harvest consisted of a red pine thinning of trees

planted 40 years ago, with every third row being taken out and cut in eight-foot lengths.

These were transported by semi-truck to the Weyerhaeuser structurewood plant in Grayling.

The remaining trees, now getting the benefit of sunlight and room, will expand and grow

more rapidly. The next cut, I’m told, will be in large poles which have more value

than sawlogs.

This material has been compiled for educational use only, and may not be reproduced without permission. One copy may be printed for personal use. Please contact Randall Schaetzl (soils@msu.edu) for more information or permissions.