Source: Unknown

Okemos was chief of the Grand River Band of Chippewa (Ojibway) Indians who camped and farmed along the Grand River from Portland, Michigan to the Red Cedar in Okemos, Michigan.

It has been said by some

that he was the nephew of the great Chief Pontiac, of the Chippewa Indians,

but there is little reason to believe that such was the case, though it

is not strange that he should, be more than willing to favor the idea

that he sustained that relation to the redoubtable Ottawa chieftain.

He is first mentioned in 1796, when he took to the warpath. Okemos and 16

others enlisted with the British and acted as a scout against the Americans.

Source:

Unknown

One morning they lay in ambush near a road cut for passage of American Army and supply wagons. A group of American troops approached and the Indians immediately attacked. Many other American troops joined the battle and the Indians were defeated. They suffered many sword cuts and gashes.

Three days after the battle,

squaws found only three men alive. Okemos was one of the survivors. He was

nursed for many months before he regained his health. He always had terrible

wounds on his forehead. One gash on his back never healed. The old records

of the pioneers always mentioned this gash. The Indians felt that he must

have been favored by the Great Spirit to survive and named him Chief out

of respect for his great courage.

Here's another version of

that battle: Okemos' first appearance as a warrior was at Sandusky

in the war of 1812, and his participation in that fight was the principal

event of his life. On that occasion eighteen young Chippewa braves, among

whom were Okemos and his cousin Manitocorbway, and who were serving as

scouts on the side of the British, had come in from the river Raisin, and

were crouching in ambush not far from the fort of Sandusky, waiting to

surprise the American supply-wagons. Suddenly there appeared a body of

twenty American cavalrymen approaching them directly in front. The red

warriors promptly made their plans, which was to wait till they could

count the buttons on the coats of the troopers, then to deliver their fire

and close on them with the tomahawk, fully expecting that in the disorder

produced by their volley they would be able to kill most of them and

take many scalps. But they had reckoned without their host. When the

flash of their guns disclosed their place of concealment the cavalrymen

instantly charged through the cover upon them, saber in hand. Almost at the

same instant a bugle blast echoed through the woods, and a few moments

later a much larger body of horsemen, warned of the presence of an enemy

by the firing, came up at a gallop to the help of their friends. The

Indians, entirely surrounded, were cut down to a man, and gashed and

pierced by saber-thrusts, were all left for dead. Most of them were so, but

life was not quite extinct in Okemos and Manitocorbway, though both were

wholly insensible, and remained so for many hours. At last Okemos returned

to consciousness, and found that his cousin was also living and conscious.

Together these two managed to crawl to a small stream near by, where

they refreshed themselves by drinking, and washing off the clotted blood,

and then, crawling, rolling, dragging themselves painfully and slowly

along the ground, they at last reached the river, found a canoe, succeeded

in getting into it, pushed off into the stream, and relapsed to a state

of insensibility, in which condition they were not long afterwards discovered

and rescued by Indians. When at last they again returned to consciousness

they were surprised at finding themselves in charge of squaws, who were

faithfully and tenderly nursing them. Both recovered, but Okemos never

wholly regained his former vigor, and Manitocorbway was little better than

a cripple during the remainder of his life. Each had been gashed with

a dozen wounds; the skulls of both had been cloven, and they carried

the broad, deep marks of the saber-cuts to their graves.

Okemos was but a common warrior in the fight at Sandusky, but for the high qualities and endurance which he showed at that time he was made a chief, and became the leader of the Red Cedar band of Shiawassee Chippewas. He obtained, through the intercession of Col. Godfroy, a pardon from the government for the part which he had taken in favor of the British, and he never again fought against the Americans. The same was the case with his kinsman, Manitocorbway.

In 1814, he presented himself to a commanding officer at Fort Wayne in Detroit and announced that he would fight no more. For his valor he was pardoned and made leader of a Red Cedar Band of Shiawassee Chippewa Indians, which was no outstanding position, but he did take the title Chief.

Okemos had enough of fighting and shortly after his recovery he and other chiefs signed a peace treaty with Lewis Cass, who was the Territorial Governor on Michigan. The peace treaty was faithfully kept.

Chief Okemos was one of the better known Chiefs, even though he was just five feet tall. He usually wore a blanket coat with a belt and had a steel pipe hatchet tomahawk and a long hunting knife. He sometimes painted his face with vermillion on his cheeks and forehead and over his eyes. You could tell if he was around because he always played his pipe or flute in the early morning.

In the 1830's, the smallpox and cholera epidemic wiped out most of that tribe and he became a wanderer, eventually making the Shimnecon area, near Portland, Michigan, his residence. Okemos was said to have four wives.

He is remembered by early

settlers as always ready to boast of his exploits and ready for a free handout.

He made his appearance at temperance picnics or any event along with 8 to

12 young ragged and dirty Indians all of whom he claimed as his children.

After the close of the war Okemos made a permanent settlement with his band on the banks of the Cedar River, in Ingham County, a few miles east of Lansing. There were the villages of Okemos, Manitocorbway, and Shingwauk, - the latter two being also chiefs. Their settlements were all located in the vicinity of the present village Okemos, and there the band remained till finally broken up and scattered. Althoughhis main settlement was in the vicinity of Okemos, Michigan, he traveled mid-Michigan and B.O. Williams recalled that in the winter of 1837, he took Chief Okemos to the Owosso school which was located then at the corner of Williams and Washington Streets. The teacher, Mr. Goodale, called the scholars to silence and Mr. Williams made a brief speech saying that he had brought a friend, Chief Okemos to see them.

He told the students,

I don't ever want you to forget that you have seen this great Indian, particularly

you young children, for when you are grown men and women you will be proud

that you once saw Okemos." A few miles south of the southern

boundary of Clinton County were settlements of the people known as Red

Cedar Indians, though they belonged to the Shiawassee bands of the Saginaws.

Their principal chief was the veteran Okemos, and next to him in authority

were Manitocorbway and Shingwauk. "The various bands," said one

historian, "all belonged to the Chippewa or Saginaw tribe. We found them

scattered over this vast primitive forest, each band known by its locality

or chief. They subsisted principally by hunting, though all had summer

residences, where they raised min-dor-min (corn), potatoes, turnips,

beans, and sometimes squashes, pumpkins, and melons."

At or near all their villages, on the Maple, the Looking-Glass, and

the Shiawassee Rivers, there were corn fields, which they planted year

after year with the same crops. The largest of the corn-fields in all

this region were those in the vicinity of Shermanito’s village on the

Shiawassee, now Chesaning. There was a small Indian orchard of stunted

and uncared-for apple-trees, and similar ones were found at several places

in both counties. The Indians carried on their agriculture in a superficial

way. Of course they were ignorant of the use of plows, and the few implements

which they had were of the rudest and most primitive kind. They had plenty

of poor and scrawny ponies, but these were uncared for, and were never

made use of except for riding. From lack of care, and the planting of

the same fields for many years in succession, these had become overgrown

with grass, weeds, and sumach-bushes, so that the crops obtained were very

meager, and but for the almost boundless stores of food furnished by

the streams and forests, the people must have been constantly in a state

bordering on famine.

It was their custom during the autumn to move from the vicinity of their fields, proceeding up towards the heads of the streams, making halts at intervals of six or eight miles, and camping for a considerable time at each halting-place for purposes of hunting and fishing. Upon the approach of winter they floated back in their canoes (carrying them round rapids and obstructions), and betook themselves to their winter quarters in comparatively sheltered places within the shelter of the denser forests. From there the young men went out to the winter hunting-and-trapping-grounds, through which they roamed till the approach of spring, when all, men, women, and children, engaged in sugar-making until the sap ceased to flow; and after this process was finished they again moved to their corn-fields, and having planted and harvested, and fished and hunted up to the head-waters of the streams during the summer and autumn, they again returned to their forest camps or villages to pass the winter as before.

Although the Red Cedar band, of which Okemos was the leader, had its settlements several miles south of Shiawassee and Clinton Counties, yet a brief mention of the old chief is not out of place for the territory was roamed over as a hunting ground for many years by him and his followers in common with the bands whose villages and fields were within its boundaries.Through all his life Okemos was (almost as a matter of course) addicted to the liberal use of ardent spirits, and in his later years (notably from the time when his band became broken up and himself little more than a wanderer) this habit grew stronger upon him, yet he never forgot his dignity. He was always exceedingly proud of his chiefship, and of his (real or pretended) relationship to the great Pontiac, and he was always boastful of his exploits. But he sometimes found himself in a position where neither his rank nor his vaunted prowess could shield him from deserved punishment. Upon one such occasion, in the year 1832, he appeared at the Williams trading-post on the Shiawassee, and, backed by twelve or fifteen braves of his band, demanded whisky. B.O. Williams, who was then present and in charge, replied that he had no liquor. "I have money and will pay," said Okemos. "You had plenty of whisky yesterday, and I will have it. You refuse because you are afraid to sell it to me!" "It is true," said the proprietor, "that I had whisky yesterday, but I have not now, and if I had, you should not have it. And if you think I am afraid, look right in my eye and see if you can discover fear there." The chief became enraged, and ordered his men to enter the trading-house and roll out a barrel of whisky saying that he himself would knock in the head. "Go in if you wish to," said Williams, carelessly, "my door is always open!" But the braves were discreet, and did not move in obedience to their chief’s order. Then Okemos grew doubly furious, but in an instant Mr. Williams sprang upon him, siezed him by the throat and face with so powerful a grip that the blood spirted; he snatched the chief’s knife from his belt and ordered him to hand over his tomahawk, which he did without delay. He was then ordered to leave the place instantly, never to be seen at the trading-house again. Disarmed, cowed, and completely humbled, he obeyed at once, and moved rapidly away followed by his braves, who had stood passively by without attempting to interfere in his behalf during the scene above described.

After the breaking up of his band on the Cedar, Okemos had never any permanent place of residence. It is said that he then resigned his chiefship to his son, and this may be true, but if there was such a pretended "resignation" it was wholly nominal and without effect, for he had ceased to have a following and therefore had no real chiefship to resign. It has also been stated that in his latter years he degenerated into a vagabond, a common drunkard, and a beggar, but this is wholly incorrect. He was certainly fond of liquor and occasionally became intoxicated, but never grossly or helplessly so, nor was it a common practice with him. Neither was he a beggar; for, though small presents were often bestowed upon him, it was never done on account of solicitation on his part, but with a considerable degree of respect. He was not infrequently entertained as a guest at the houses of people who had known him in his more prosperous days.

The Chief never lost his dignity and was a proud man until he died in 1858, at an Indian settlement near Portland. He was buried near Okemos Rd. on State land within the "oxbow" of the Grand River. Okemos died on the 4th of December, 1858, at his camp on the Looking Glass River, in Clinton County, above the village of DeWitt. His remains - dressed in the blanket coat and Indian leggins which he had worn in life - were laid in a rough board coffin, in which were also placed his pipe-hatchet, buckhorn-handled knife, tobacco, and some provisions; and thus equipped for the journey to the happy hunting-grounds, he was carried to the old village of Peshimnecon, in Ionia County and there interred in an ancient Indian burial-ground near the banks of the Grand River.

Source: B. Pomper

The age of Okemos at his death is not known. Some writers have made the loose assertion (similar to those which are frequently made in reference to aged Indian chiefs) that he was a centenarian at the time of his death, while others have reduced the figure to between eighty and eight-five years. The fact that until the end of his life Okemos was lithe in body and elastic in step, showing none of the signs of extreme old age, renders it probable that the year mentioned was nearly the correct date of his birth, which would give him the age of seventy years at the time of his death.

Source: B. Pomper

The Michigan Legislature renamed the village of Hamilton to Okemos, in his honor in 1859.

An article published in the Portland Observer of 1873 gives the following account of his death and burial.

"On a bleak day on the 6th of December of 1858, a small train of Indians entered DeWitt, having with them drawn upon a hand sled the remains of an old Indian Chief of the tribe of the Ottawas. The body was that of Okemos and they who accompanied it were his only kindred. They brought it from five miles northwest of DeWItt where he had died on the previous day.

They brought tobacco and filled the pouch, powder for the horn and bullets for the bag. They also brought, contrary to the usual custom of their race, a coffin in which they placed the remains and then took up their silent march toward the Indian Village of Shimnecon on the Grand River, twenty-four miles below Lansing, near Portland, the principal residence of the Chief."

Hall Ingalls tells an entirely different story. He was known to be a friend of Chief Okemos and even spoke the Indian language and was working on the mission house in Shimnecon at the time. He claims that Okemos died there after an illness of several days and he was asked to bury the Chief. A direct quote from a newspaper article follows though it is not documented for name and date.

"The grave the Indians

dug was larger than usual, for it had to hold the personal effects of the

chief as well. It was four feet deep, seven feet long and wide. Mr. Ingalls

had the Indians gather bark, a floor was laid on the bottom and the grave

was also sided with bark.

It was so close to the

hut where the remains were lying that but a few steps were required. The

body was lowered and then covered with blankets. Blankets were placed under

the head so that the August sun fell upon the face. At the Chief's right

side were his two guns. At his left his tomahawks, scalping knives and other

personal effects were placed and over the whole went another blanket as a

shroud. Bark was then laid over the whole and the grave was filled with

earth."

Three years later the brother of Mr. Ingalls interupped vandals at the gravesite as they were digging for what they thought might be valuables said to have been buried with the Chief. The Ingalls brothers quickly placed a number of stones in the hole which had been dug.

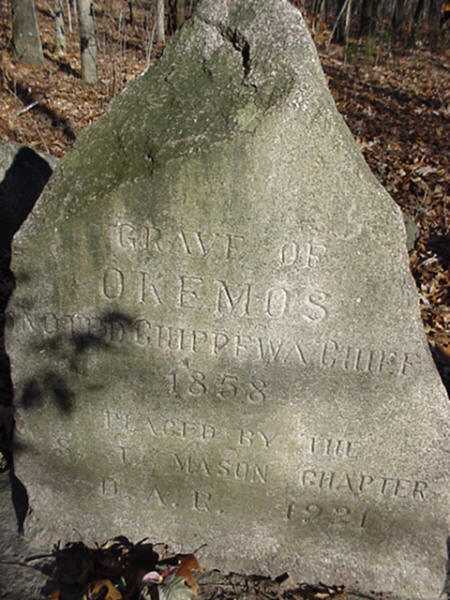

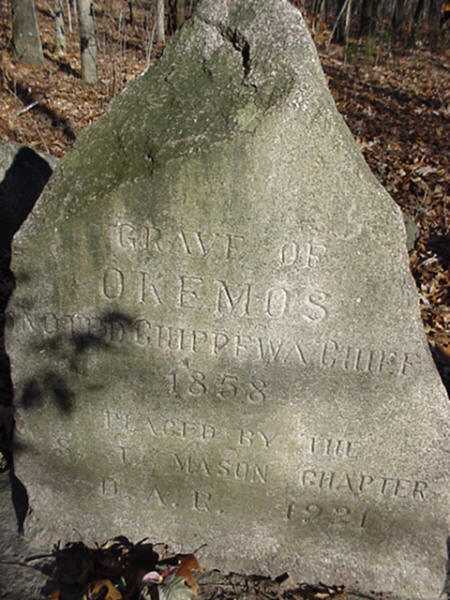

In 1921 the Daughters of the American Revolution (D.A.R.) wished to place a gravestone at the site honoring the Chief. Mr. Ingalls was able to vouch for the fact that this was indeed the site of the grave of Chief Okemos.

The gravestone is located south of Portland and is perhaps a half mile walk back from the main road on State land in the oxbow of the Grand River. This area sits high atop the river and is one of the most peaceful spots in the State of Michigan.

The Central Elementary School in Okemos, MI, across the street from the site of Okemos' camp, has a marker that says:

"Brave in Battle"

"Wise in Council"

"Honorable in Peace"

**Okemos, or Ogemaw, meant, in the Chippewa language, "Little Chief," and Che-ogemaw, "Big Chief." Whether the name "Little Chief," as applied to this Indian, had reference to his small stature (as he was very short) or to the extent of his power and authority as a chief, does not appear.

This web page is taken, in large part, from <project..angelfire.com/mi2/shiawasseetours/okemos.html> and the HISTORY OF SHIAWASSEE AND CLINTON COUNTIES, MICHIGAN (1880) by D.W. Ensign & Co.This material has been

compiled for educational use only, and may not be reproduced without

permission. One copy may be printed for personal use. Please contact Randall

Schaetzl (soils@msu.edu)

for more information or permissions.