Michigan mint growers have a strong market for their crop with the flavoring used in a wide assortment of products. It is used in baking, candymaking, coffee, cocoa and many other products. In 1997, Michigan growers produced 51,000 pounds of spearmint. Peppermint is also grown in Michigan.

The oil extracted from mint through a steam distillation process is highly concentrated. One pound will flavor 135,000 sticks of gum. Chewing gum companies regularly blend mint oils to maintain a consistent and specific flavor. An advantage to growing mint is farmers may store the soil for several years if market prices fall.

Peppermint (Mentha piperita, named for its pepper-like taste) and spearmint (Mentha spicata, named for its arrow-shaped flower spires) are related plants that are rich in volatile oils called terpenes.

Click here for full size image (213 kb)

Source: Photograph by Randy Schaetzl, Professor of Geography - Michigan

State University

These ethereal, complex organic compounds---mainly menthol and carvone---give mint the

taste and aroma that make it a favorite for chewing gum, toothpaste, candy and

medicine. The two mint plants are believed to have originated in the Mediterranean

basin, where their earliest uses were for fragrance and flavoring, especially in medicinal

products.

Source: Image courtesy Michigan History Magazine

A Bit of History

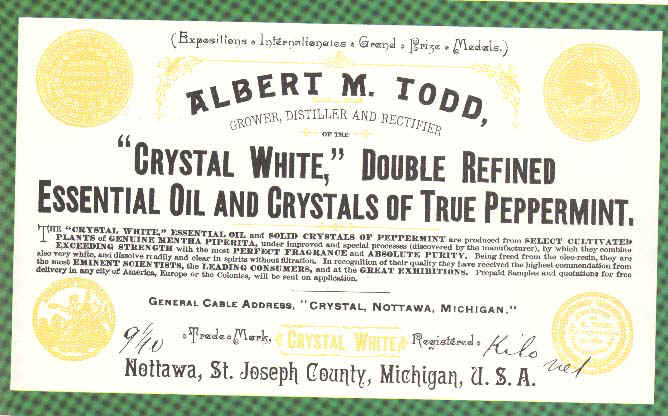

In Michigan’s early years, mint was grown primarily on the dark, flat prairie soils

of the southwestern lower peninsula. Many farmers in St. Joseph County (see below) grew

peppermint in the county’s bur oak openings. By the end

of the Civil War, mint production in St. Joseph had increased so much that Michigan

rivaled national leader New York as the primary source of supply. Following the Civil War,

mint cultivation spread from St. Joseph, first west into Cass and Berrien, then north into

Van Buren, Allegan and Kalamazoo counties. By the turn of the century, 90% of the

world’s supply of mint oil came from an area within a 90-mile radius of Kalamazoo.

Source: Image courtesy Michigan History Magazine

During the 19th century Michigan mint was primarily grown on natural prairies and in

burr oak openings. While these soils generally supported a decent crop, they were often

excessively windblown and incapable of shielding sensitive plants from winterkill. To

escape these problems, mint farmers in the late 1880s shifted their operations to organic soils, or mucks, which until then had been generally

unused for agriculture. These "mucklands" offered better protection and rich

earth, which significantly increased the yield of mint fields. Furthermore, muck soils had

a large water-holding capacity, an important feature for a crop with high moisture

requirements. By raising or lowering gates in drainage canals, mint farmers could keep the

water table near the surface during the growing season and then drop it when harvesting

demanded dry fields.

The low-lying mucklands (below) with their fertile, black soils,

however, brought new problems.

Click here for full size image (262 kb)

Source: Photograph by Randy Schaetzl, Professor of Geography - Michigan

State University

Poor drainage could retard cultivation and harvesting, flood the crop in wet times or

require extensive ditching projects. Also, the growing season in the mucklands was

restricted because they were susceptible to frost late in the spring and early in the

fall. Nevertheless, the superior yields of muck soils, which require drainage ditches to

keep the water table lower than the soil surface (see below) far outweighed their

disadvantages, and by the mid-1880s the switch was complete.

(In the image below, mint is being grown in the field on the left; note the full drainage

ditch on the right.)

Click here for full size image (255 kb)

Source: Photograph by Randy Schaetzl, Professor of Geography - Michigan State University

Mint "Technology"

Despite the productivity of Michigan’s mint fields, Michigan mint growers at first

had difficulty selling their harvests because of unscrupulous farmers who adulterated the

oil with turpentine, alcohol or fireweed. Even if those who raised the crop were honest,

dealers might dilute the oil to increase their profits. Since there were no established

tests for determining the purity of mint distillates, it was difficult to guard against

these practices.

Eventually, mint husbandry was improved by establishing two commercial

experimental farms, one in northeastern Van Buren County and one in central Allegan

County. On these plantations research was undertaken to develop hybrid mint plants and

better related agricultural techniques. Significant advances were made in distillation

technology and better rootstocks were introduced. The latter achievement was based on

Black Mitcham mint, a hardy variety imported from England because it produced a higher

quality and quantity of mint than domestic plants. At the turn of the century Michigan was

the largest producer of peppermint oil in the world.

Since the commercial mint plant (below) is a sterile, complex perennial that seldom

produces seed, planting a new mint field required a source of rootstock.

Source: Photograph by Randy Schaetzl, Professor of Geography - Michigan

State University

For this purpose an old field with healthy growth was plowed to expose the individual

roots. These roots were hooked from the upturned soil by hand or pitchfork. To keep these

runners from drying out workers piled them into small heaps and covered them until needed.

One person could manually plant only one acre of mint every 12 hours, and the roots from

185 square meters of an established field sufficed for a usual day’s labor.

Before transplanting could occur, the new area had to be readied. This

process consisted of plowing and disking the field. Next, the mint stolons or

runners--about a quarter inch in diameter and one to three feet long--were placed in a

carrying sack, manually separated and strung along each trench, end to end. The person

doing the hand planting then covered the roots with soil, and the ground was lightly

dragged to ensure a good start.

If the planting was properly done and the weather cooperated, sprouts

appeared about every 10 cm along each furrow, about two weeks after planting. From this

stage the roots grew up and out, spreading laterally until by late summer they had formed

a solid green mat. Because yields from mint fields usually declined each year, lands were

customarily plowed up every 3-5 years and either restored with new roots or given over to

other crops. Resting the soil from monoculture helped improve fertility and reduce

disease, so mint farmers usually chose the latter option.

Source: Image courtesy Michigan History Magazine

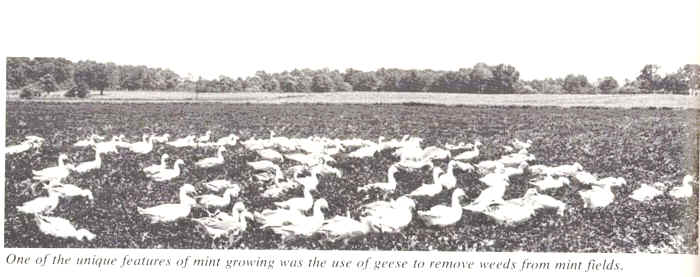

Weeds in mint produce an inferior oil. Weeding, done by hand, began shortly after

planting. Even after farming became mechanized, weeding remained largely a manual task

because the delicate mint plants were easily injured by tractors and their implements. In

an attempt to lower production costs and labor demands, farmers experimented with grazing

animals to weed the fields. Since livestock do not eat spicy mint leave, cows, goats and

sheep were used to consume the unwanted vegetation. Though these beasts removed the weeds,

their hooves damaged the crop. Geese, on the other hand, performed the weeding with no

adverse effects (see below).

Source: Image courtesy Michigan History Magazine

The annual harvesting of mint usually began in late July or early August, when the

plants were about two feet high and at 10% of full bloom. The crop was mowed by hand, much

like clover, and then placed into windrows to dry. After curing to the wilt stage, the hay

was loaded on wagons or placed in special containers and taken to the still.

Initially mint oil was distilled by using a copper kettle and a

condenser pipe, much like the traditional moonshine stills of Appalachia. This slow method

of extraction yielded only 12-15 pounds of oil per day.

The introduction of the steam distillery in 1846 increased production

to over 100 pounds of oil daily. In this process the copper kettle was replaced by large

wooden vats about two meters in diameter and from 2-3 meters deep. Each tub was connected

to a boiler from which it could draw steam. After one to two tons of mint hay had been

loaded into a vat, the cover was tightly secured and a condenser coupled to the lid. Once

the distilling apparatus had been charged with hay and readied, steam was forced into the

bottom of they wooden chamber. The mint oil, primarily contained in glands on the lower

surfaces of the leaves, was freed by the heat and carried upward with the steam to the top

of the vat. There, the hot vapors entered a cool condenser, which converted the steam to a

mixture of mint oil and water. This fluid flowed into a separator, where the oil, which

collected on top, was skimmed off. Each load yielded about 12 pounds of oil. It took an

acre of mint to produce 30 pounds of oil.

The mint oil created by this procedure was drained into cans, and could

be stored for several years without damaging the oil’s quality. The relatively

tasteless vegetative matter that remained in the vat was removed, dried and fed to

livestock. When the mint season was over, a few factories turned to distilling such things

as wormwood, tansy, erigeron, wintergreen, sassafras or pennyroyal. Most operations,

however, were privately-owned, one-use stills that were shut down in the autumn and not

refired until the next year’s mint cutting.

Scientific knowledge has also led to many improvements in the

processing of mint. Distilleries have been consolidated and automated so that they hardly

resemble the operations of a decade ago. Now the mint hay is sliced into cm-long pieces

before being treated, an operation that reduces the amount of steam needed to extract the

oil (see below).

Source: Photograph by Randy Schaetzl, Professor of Geography - Michigan State University

This chopped mint is no longer dumped into a vat and then forked out after cooking.

Instead, the cuttings are loaded into large, portable, metal receptacles that can be

mechanically moved in and out of distillation tubs.

Source: Photograph by Randy Schaetzl, Professor of Geography - Michigan State University

In the more modern facilities, the hay is picked up by a field chopper and blown into

wagon-mounted tanks (below) that are designed to serve as individual steam chambers,

eliminating even more handling.

Source: Photograph by Randy Schaetzl, Professor of Geography - Michigan State University

Note the wagon below, which is empty but is nonetheless showing how steam can be driven

into the wagon. (The steam is exiting the opening in top, which would be closed if

mint were in the wagon.) The steam is forced through the chopped mint plant parts,

and the oils, which become volatile and leave the plant per se, exit the mint wagon with

the steam. In a normal operation, therefore, the wagon would be closed up tight and

the steam would enter the wagon at one spot, while mint oil and steam would leave the

wagon at another.

Source: Photograph by Randy Schaetzl, Professor of Geography - Michigan State University

When full, these wagons/containers are towed to the distillery (below) and hooked

directly to the steam lines and condenser.

Source: Photograph by Randy Schaetzl, Professor of Geography - Michigan State University

In about one hour the distillation process is complete. The spent charge is hauled away

and dumped (much like a load of sand) through a large door in the rear of the hopper.

Uses of mint oil

Initially, mint oil was used mainly for medicinal purposes, but the

popularity of both chewing gum and toothpaste in the early 20th century provided a new

market. Today 70% of US mint oil is consumed in the United States, and 40% of that goes to

improve the taste of gum and 30% to toothpaste and mouthwash.

Today, a lot of mint is grown in and around St. Johns (just north of

Lansing). Farms like the Crosby Mint Farm still grow mint and distill it on site.

The smokestack of the distillery is even evident in the background of the image

below.

Source: Photograph by Randy Schaetzl, Professor of Geography - Michigan State University

Michigan ranks sixth in the nation in spearmint production. Michigan’s

1993 spearmint crop totaled 90,000 pounds of oil valued at $1,260,000. Growing conditions

were poor, with early season cool temperatures and excessive rain. Conditions mirrored

last year and yield was similar at 32 pounds per acre. Most Michigan spearmint goes

to processors which produce oil to be further refined for use in such products as gum,

medicine, soap, and toothpaste. Fresh mint leaves are used in restaurants for garnishes.

The major producing area is Central Lower Michigan.

Mint is also claimed to have medicinal properties, and now modern

science seems to agree. Read on.....

Tummy trouble? Try taming it with peppermint oil. If you're bothered by irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), which affects 20% of Americans--twice as many women as men--give peppermint oil a try. Long considered a folk remedy, several studies have shown that IBS sufferers who took peppermint oil capsules reduced their symptoms significantly compared to patients who took a placebo. Researchers believe the oil relaxes the smooth muscle in the lining of the intestine, which reduces muscle spasms. The recommended dose is 90 milligrams three times per day, preferably with a meal. Because peppermint oil can trigger acid reflux, make sure that you take the coated-capsule form. This will reduce your chances of getting heartburn.

This material has been compiled for educational use only,

and may not be reproduced without permission. One copy may be printed for

personal use. Please contact Randall Schaetzl (soils@msu.edu)

for more information or permissions.