LOW LAKE LEVELS

"The lakes are the driving force behind our economies," said Paul Begin,

Quebec's minister of environment. "As they drop, the issue of who owns them and uses

them is going to be a growing concern."

But specifically, what problems do low

water levels pose?

In 1999, low Great Lakes water levels prompted the following concerns. New islands were

emerging and existing ones were expanding as water levels continued to decline. Lakes

Michigan and Huron had fallen by 15 inches from levels recorded in 1998, followed by Lake

St. Clair, 13 inches, Lake Erie, 12 inches, and Lake Ontario, 3 inches. According to U.S.

Army Corps of Engineers forecasts, Lakes Michigan and Huron were projected to drop another

2 inches, along with Superior. Lake St. Clair may decline by 3 inches, and Erie by 1 inch.

No change in Ontario’s level is expected. The low water "phenomenon" raised

new issues that have to do with the environment, property rights and government’s

role in managing the new lands.

"We have islands popping up too fast to name them," said Doug

Spencer, manager of the Shiawassee National Wildlife Refuge, which oversees the Charity

islands in Lake Huron’s Saginaw Bay. Bird species are flocking to the newly emerged

islands, which have little or no vegetation. If the Great Lakes continue to recede and

remain low, grasses, shrubs and trees eventually will grow, perhaps attracting raccoons,

coyotes, deer and wolves. "Lower waters will mean that deer and predators can

actually wade out and colonize some of these islands," said a Michigan Department of

Natural Resources biologist familiar with Saginaw Bay and its wildlife.

As rocks, wrecks and dock pilings break surface beside murky landmarks

not glimpsed since the 1960s, lower lakes raise hazards above and below the surface, and

are reviving waste chemicals stored within bottom sediments to risk ingestion by fish,

birds and people.

Among the impacts:

_ Intense dredging may be causing the most lasting damages from

continuing lake declines. Buried chemical compounds, pesticides and heavy metals flushed

into the Great Lakes during 100 years of industry are being freed to again enter the food

chain.

_ The 1,000-foot

freighters hauling iron ore, coal and stone that fuel the Midwest's industries are

limiting their loads to avoid hitting bottom. Harbors and channels they travel are

dangerously shallow, leading to a doubling in dredging.

_ Pleasure boaters

have seen boat launches, docks and piers rendered useless. Unable to dredge, a score of

recreational harbors in Michigan and Ontario are all but shut.

_ Scientists are unsure how falling waters will influence 150

species of native fish and the exacting balance between them. They note that fish near

shore are losing spawning habitat.

_ With hundreds of intakes piping drinking water from the lakes,

health experts also worry about threats to purity.

_ Politicians and government officials are uneasily debating

solutions to low water.

Rocks, boulders and lost docks emerge from low lake waters

(from a 2000 Detroit News article)

Residents of lakefront property in Michigan's Thumb region know that, during low lake

levels, the Thumb has a sharp and stony thumbnail. From Grindstone City south to

Lexington, Lake Huron's low waters expose a sea of shoreline stones and boulders.

"For 50 yards in front of me, all I see are rocks," said

Robert Banyai, a Grindstone City resident who lives on what used to be lakefront property.

"My boat sits on dry land because we can't carry it back and forth to the water.

Nobody has ever seen so many rocks."

As the lakes rise and fall, which is totally natural,

"location" is deciding whether Great Lakes property owners view low water levels

as disaster or paradise. Areas that often suffer erosion from rising waters sit

comfortably above the water line. On Lake Michigan's shore, for example, residents enjoyed

the steamy summer of 1999 on the ever-expanding beach. "Oh, we like this,"

crooned John Boyd, whose lakefront house is in Holland. Two summers ago, in 1998, high

waters broke over his protective sea wall and eroded the property's sandy bluff. Years of

harsh storm flooding in the 1980s provoked Boyd and other Lake Michigan owners to ask

federal officials to design stronger mechanical controls for lake waters. They want Lakes

Huron and Michigan kept five inches below their average level. To date, officials have

refused, citing cost and possible environmental damages.

Memories are Short

Like many things, society's memory of ebbs and flows of Great Lakes water levels doesn't

last very long. During prosperous times shoreline construction booms, some of which is

under way next to land that was submerged less than a decade ago. "We're watching

developers creeping closer and closer to the lake's edge," said David Knight, who

lives in East Jordan, near Lake Charlevoix. The cities of Charlevoix, Petoskey and

Traverse City, in the state's northwestern fruit belt, are favored places for vacation

cottages. "We kind of chuckle about it, said Knight, editor of the Great Lakes Seaway

Review, a shipping trade magazine. "There's going to come a day when they wish they

hadn't built there. People's memories are so short."

Lake Superior's fluctuation is charted in inches and has not caused

widespread property damage. But hundreds of miles downstream on Lake Ontario, the last

lake in the system, declines are being counted in feet and thousands of dollars. Sea walls

built to combat high levels collapse during low levels, from an absence of water pressure

to support them. "My retaining wall is cracked and leaning, and I'm looking at a

price tag of $25,000 to replace it," said Mary Lou Fischer of Somerset, N.Y., a

village between Buffalo and Rochester. Fischer lost 30 feet of beach property when Ontario

rose in the 1980s, then patched and fortified her wall as a prudent defense against future

floods. She believes shoreline property owners on all the Great Lakes should be eligible

for federal aid to cope with water fluctuations.

Here's an excerpt of an Associated Press article, dated January, 2000.

Great Lakes dredging requests on the rise, but efforts to counteract

dropping water levels also bring up pollution

DETROIT- With federal forecasts predicting the water level in three Great

Lakes this summer (2000) could drop as much as 10 inches below last year’s record

lows, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers has already received 225 dredging requests for

Michigan. That’s a 27 % rise over the same period last year.

"Water levels are the hot issue right now (January). But just wait

until spring," said Dr. Michael Donahue, director of the Great Lakes Commission, a

policy group in Ann Arbor that advises state and federal officials. "It’s going

to get hotter as soon as people try to put their boats in the water."

The water in lakes Michigan, Huron and Erie sunk to their lowest level

in three decades last year (1999). Below-average snowfalls in the winter of 2000 added to

the problem, and the lake levels might fall 10 inches in the next five months. During

1999’s record-low levels, there were 1,000 dredging projects along Michigan’s

coasts--an increase of 110 % over 1998. Several Detroit-area communities have already

applied for dredging permits, including Grosse Pointe, St. Clair Shores, Grosse Pointe

Farms and Grosse Pointe Shores.

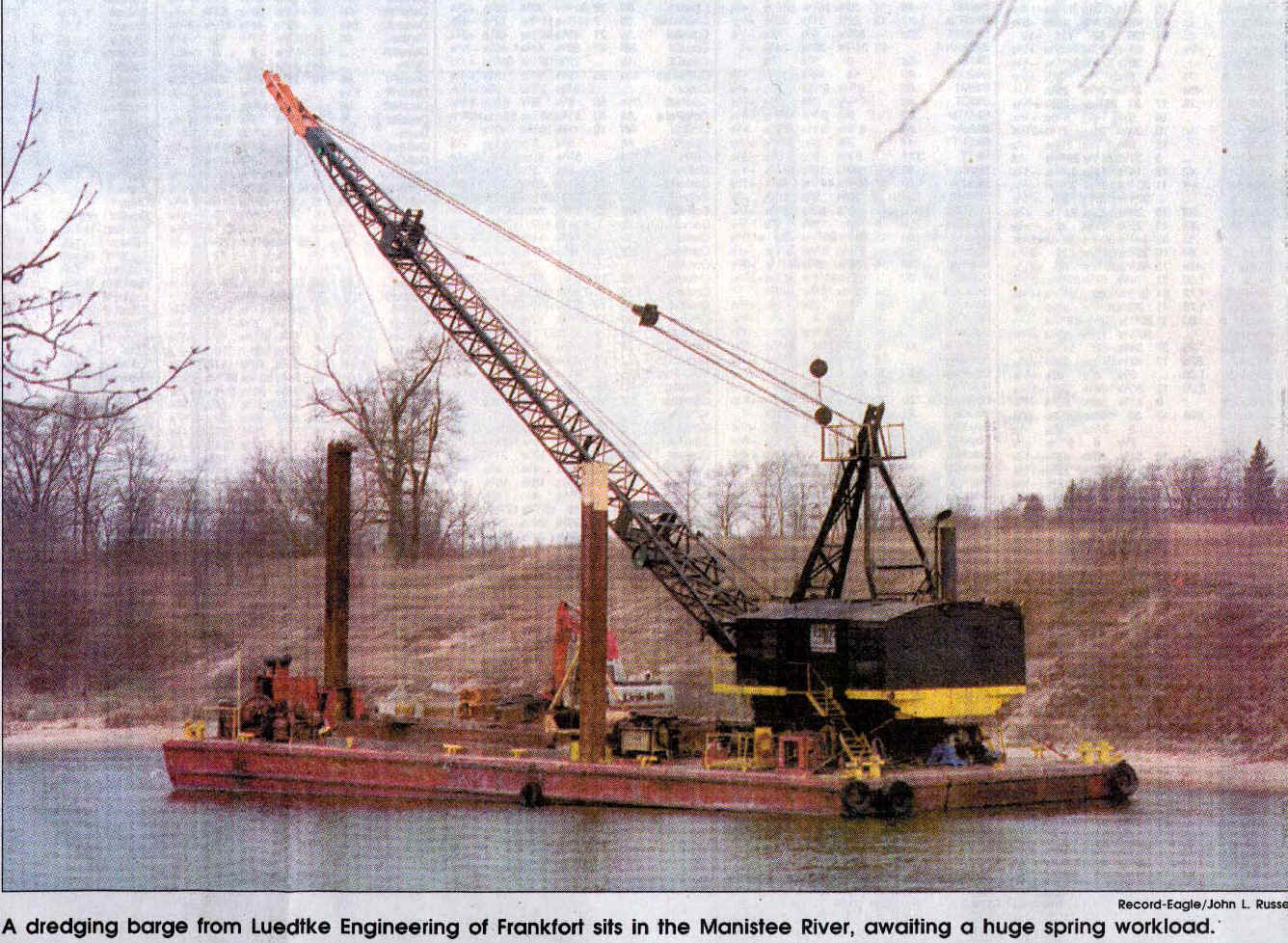

A dredge ship, in dock.

"We have to do something," said Dick Huhn, director of parks

and recreation in Grosse Pointe Farms, which maintains a lakeside park with its own

281-slip marina. "People have been running aground. If we don’t dredge, we think

we’ll lose half of those boat slips. That would upset a lot of residents."

There is a problem, however, with so much dredging. Many sites where

dredging takes place on the Great Lakes are polluted. At least 30 sites along the Detroit

River’s bottom are polluted with heavy metals such as lead, nickel and cadmium, farm

pesticides including DDT and toxophene, and diesel fuel, according to federal studies.

"Half of all dredged material in the Great Lakes is contaminated.

That’s 2 million cubic yards of dredge every year," said Steve Thorp,

Michigan’s delegate to the Great Lakes Dredging Team. "The question is: Where

are we going to put it all?"

State and federal officials said there isn’t much space inside

confined disposal facilities, the storage areas where polluted dredge has to be deposited

by law. Thorp said continued dredging could "fill those right up." Clean dredge

can, however, be used to nourish beaches and build roads.

DREDGE (below):

And from the Detroit News (February, 2000):

Lake levels worry boaters. State rules restrict spring, summer dredging

ST. CLAIR SHORES -- Facing ever lower waters, Lake St. Clair boaters soon may feel the

pinch of recent state rules strictly limiting when they can dredge marinas, canals and

boat slips. Metro Detroit boaters may be unaware of it, but Michigan DNR officials

forbid most dredging on the lake between April 1 and Sept. 30. That leaves only a

narrow window for work between the melting of lake ice in March and the first days of

spring. Surface ice shuts down dredging during winter months. The reason behind the

rule: Scientists are worried that sediments stirred during summer months harm lake fish

during critical seasons of spawning.

"When fish spawn, eggs and the young fish are very fragile,"

said a fish biologist at the Department of Natural Resources. "Dredging creates a lot

of silt blooms. When it's thick, it will greatly diminish the survival of the young

fish." The ban applies to Lake St. Clair's western shore, the Detroit River and

some areas of Lake Erie. It's intended chiefly for shallow shoreline areas. Deeper

channels used for commercial shipping generally aren't considered to be important for

spawning fish.

The Department of Natural Resources ordered the dredging ban during the

spring and summer seasons two years ago, after scientists concluded there was a credible

threat to fish. Low water levels throughout the Great Lakes are now prompting experts to

test bottom sand and silt for PCBs, heavy metals, pesticides and other long-lived

chemicals. One danger comes from fish picking up toxic chemicals once again suspended in

the water. Contaminated fish, in turn, may be eaten by anglers.

Lake St. Clair has recorded the second-largest two-year decline in

water levels in the last 100 years. Between 1997 and 1999, the lake went down by nearly

three feet, stranding boaters on new sand bars and keeping others from ever leaving the

dock. Harrison Township residents Jim and Doris Hazemy have had to find a new marina

for their 37-foot cruiser. "There's not enough water for us to keep the boat in the

marina," said Jim Hazemy. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, which oversees all

Great Lakes dredging, reported a 110% increase in applications from 1998. In past four

months, Corps officials saw a 27% rise in applications over the same period last year.

And this article, a month later in the Free Press, explains who wins out in the degredging

battle---boat-owners who pay taxes or fish that do not.

Spawning fish may be put at risk. Dredging to help pump up Lake St. Clair levels

NOTE by Schaetzl: dredging does not affect lake levels, it only lower the lake bed!

The Lake St. Clair boating season -- and the millions of dollars that boaters spend -- is

saved, but a couple years' worth of fish might be lost in some areas. Faced with the

lowest water levels since the early 1960s, state and federal officials are suspending

rules that prohibit dredging during spring and summer months when fish are spawning. Water

levels have dropped about 40 inches in Lake St. Clair in three years.

The decision Friday will suspend the long-standing ban on dredging in spawning areas in

and around most parts of Lake St. Clair and the Detroit River from April 1 to Oct. 1.

Harrison Township Supervisor John Hart said he was surprised, but excited, that the

decision was made so quickly. "I'm glad that they're doing that," he said.

"It's going to be a big help because Harrison Township is heavily dependent on the

marine business."

Many canals, harbors and marinas are now too shallow for the boats that

usually dock in them. Dredging, using heavy equipment to scrape the bottom of waterways to

make them deeper, stirs up sediment that chokes fish eggs before they

hatch. That's why digging is usually banned around boat wells and launches usually while

fish are spawning and fish eggs are developing. Losses in the Lake St. Clair

fishery will be evident in two to four years when anglers would have begun reeling in fish

hatched this spring. As little as one millimeter of sediment can kill a fish egg.

But state DNR biologists say the fishery likely will recover by the end

of the decade. Not all species of fish will be affected equally by the increased dredging.

Some are more sensitive to silt and some typically spawn further north. In addition,

the shallow waters of Lake St. Clair's Canadian side are favored spawning grounds for many

fish. Canadian officials could not be reached Tuesday to comment on if they plan to change

their dredging rules in response to lower water levels.

State or federal permits are required to dredge in Michigan.

Officials were counting on word-of-mouth to spread news of the new

policy as they respond to dredging permit inquiries over the next few weeks. "We

realized that the boaters of southeast Michigan were faced with an impossible

situation," said a supervisor for the DEQ's land and water management division.

"Short of shutting down the whole boating season, some changes had to be made."

A study by Michigan State University researchers concluded that in 1998 spending

related to recreational boating in Macomb, Wayne and St. Clair counties totaled $150

million.

Dredging rules vary widely across the state, depending on water

temperatures and when fish are spawning. In general, however, regulators do not allow much

dredging in rivers, canals, flats and other places where fish spawn between April and

October. The new rules for Lake St. Clair and the surrounding area are complex and

still restrict dredging in some circumstances, including open marinas that are not

protected by coves. Dredging will be allowed throughout the spring and summer in most

canals, but where it is allowed, contractors must use silt curtains, which are pieces of

cloth anchored and held up by buoys. They are designed to help contain drifting silt.

St. Clair Shores Mayor Curt Dumas, who also runs Jefferson Beach Marina on Lake St. Clair,

said Tuesday the new dredging policy is great news. "It would have crimped many

people's summers, had they not done this," he said. "St.

Clair Shores really comes alive in the summer. Without that influx a lot of people

would be hurt, not just the marinas, the bait stores, the party stores and the waterfront

restaurants."

Van Snider Jr., executive director of the nonprofit Michigan Boating Industries

Association, also was pleased with the decision to loosen the dredging ban. "Other

areas in the state need the same consideration," he added.

On Tuesday, Gov. John Engler announced that he is earmarking $14 million of previously

unallocated funds in the state waterways commission budget for dredging some public

harbors and marinas. Local governments with control over selected

marinas may apply to state government for grants that would cover 75% of their dredging

costs.

"We can't cause rain and snow to help fill the lakes up, but this

is one way to get at the problem," said Engler spokesman John Truscott.

Impacts of low water on Lake Superior and the Soo area

If the Great Lakes have a pressure point, it can be found at the Sault Ste. Maries, two

small sister cities that gaze at each other across the St. Marys River at the remote base

of Lake Superior. One Marie is Canadian; the other Marie is Michiganian. Between them

stretches the St. Mary’s River, with its complex span of ships' locks, water gates,

frothing rapids and hydroelectric generators, with which both nations harness the icy

source of all lake waters.

In low water years like 1999, Lake Superior's lower water levels and

weak flows in the St. Marys hamper shipping traffic, cut hydro-electric generating power

production. and possibly starve fish. Little or nothing can be done about it, federal

officials say. "People think there's a red button we push to increase the flow of

water, but it's not that easy," said Doug Cuthbert, an Environment Canada water

expert. "We're trying to control something that is really beyond our control,"

he said.

# Low levels expose often competing interests of shipping

companies, power plants, local fishermen and environmentalists. Fourteen-foot row

boat or 1,000-foot freighter, every ship that seeks to pass this point must ride a watery

elevator called a lock. Lake Superior sits 21 feet above Lake Huron. Traveling east to

west-Huron to Superior-the elevator goes up. From west to east, it goes down. America

controls four of the five locks, which handle the bulk of commercial traffic. "Our

records show fewer vessel passages and a 9.4% decline in tonnage passing through this year

(1999)," said Stanley Jacek, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers official who supervises

the American locks. "Less water has meant trickier navigation, less trade and less

revenue for the U.S. government."

# Power generated by Edison Sault Electric fell by 50% during

three months this spring, then crept back toward normal as water from snow melting in

Ontario entered Lake Superior in the summer. Edison Sault lights most of the eastern UP

and Mackinac Island. It supplies 21,000 customers. "We try to keep the plant running

full bore, but we're still down 5-10% of our capacity,"

This material has been compiled for educational use only, and may not be reproduced without permission. One copy may be printed for personal use. Please contact Randall Schaetzl (soils@msu.edu) for more information or permissions.