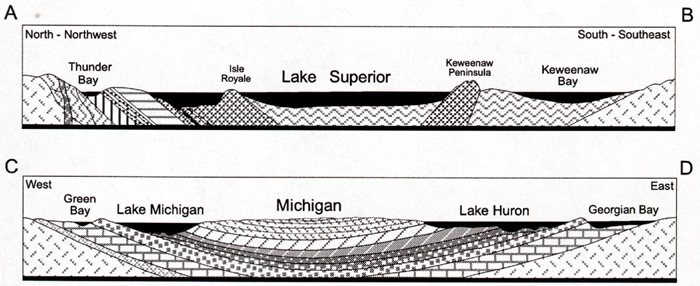

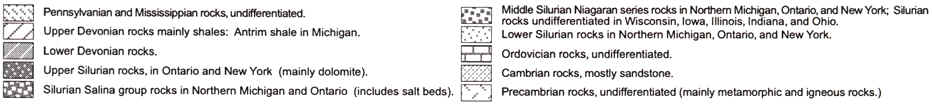

The diagram below shows what the structure of the rocks would look like, along transects A-B and C-D.

GEOLOGY

The underlying bedrock of Michigan is mostly hidden from view by unconsolidated

material deposited during continental glaciation. However, there are a number of places in

the Lower Peninsula where the bedrock can be seen such as in rock quarries and in outcrops

along rivers and lakes. In the western Upper Peninsula, a considerable amount of bedrock

is visible.

The geologic formations of Michigan span more than 3.5 billion years,

from some of the oldest Precambrian rocks to loose, unconsolidated drift left behind by

the continental ice sheets of the Pleistocene period.

Source:

Image Courtesy of Randy Schaetzl, Professor of Geography - Michigan State

University

The diagram below shows what the structure of the rocks would look like, along transects

A-B and C-D.

Source:

Unknown

Two major rock types are found in Michigan. The Lower Peninsula and the eastern parts

of the Upper Peninsula are underlaid by a series of sedimentary rock layers: The Michigan

Basin. These rock formations, consisting largely of shales, limestones, and sandstones,

were deposited on the bottom of ancient seas that covered Michigan on and off for millions

of years. The basin is estimated to be about 14,000 ft (4,267 m) thick, and its rocks rest

on the top of a very old Precambrian surface. The various layers of sedimentary rock are

piled up on top of one another like a series of saucers.

The ancient igneous and metamorphic rocks that compose the Precambrian,

or Canadian, Shield in the western part of the Upper Peninsula make up the second category

of rocks and are estimated to be at least 3.5 billion years old. The igneous rocks are

hard, crystalline, resistant to erosion, and are largely made up of granites and

metamorphic rocks--rocks that have been changed through heat and pressure--composed mainly

of gneisses and schists. The higher areas in the Upper Peninsula are the remnants of

ancient peaks that have been worn down over millions of years by the erosive action of

wind, water, and moving ice. Thus, the Porcupine and Huron mountains in the western half

of the Upper Peninsula have been greatly altered over their long geologic history through

uplift and erosion and are now only remnants of once-high mountains.

Both major types of rocks found in Michigan are important to humans.

The igneous type contains valuable minerals such as iron ore and copper, and the

sedimentary rocks contain petroleum, natural gas, salt, gypsum, and limestone.

Source: Unknown

Source: Unknown

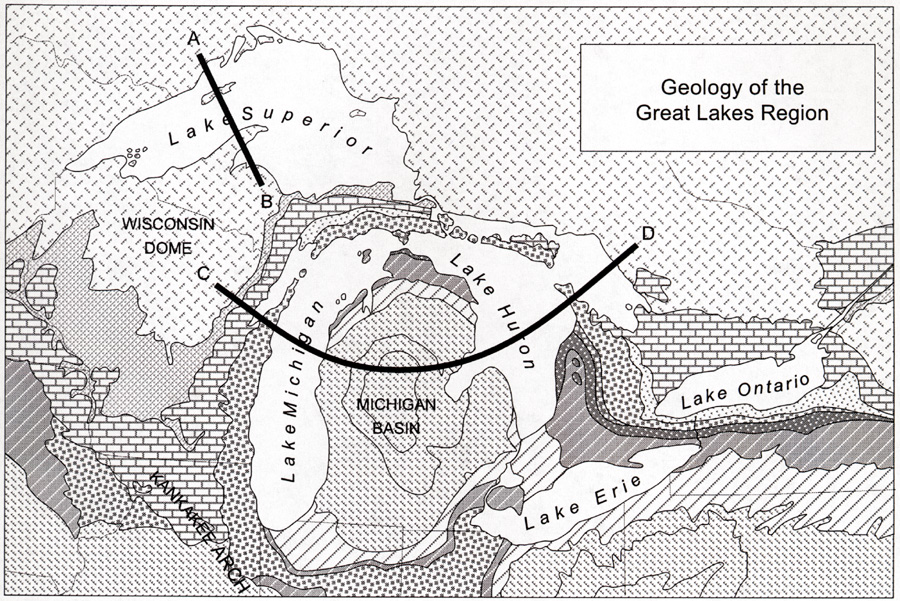

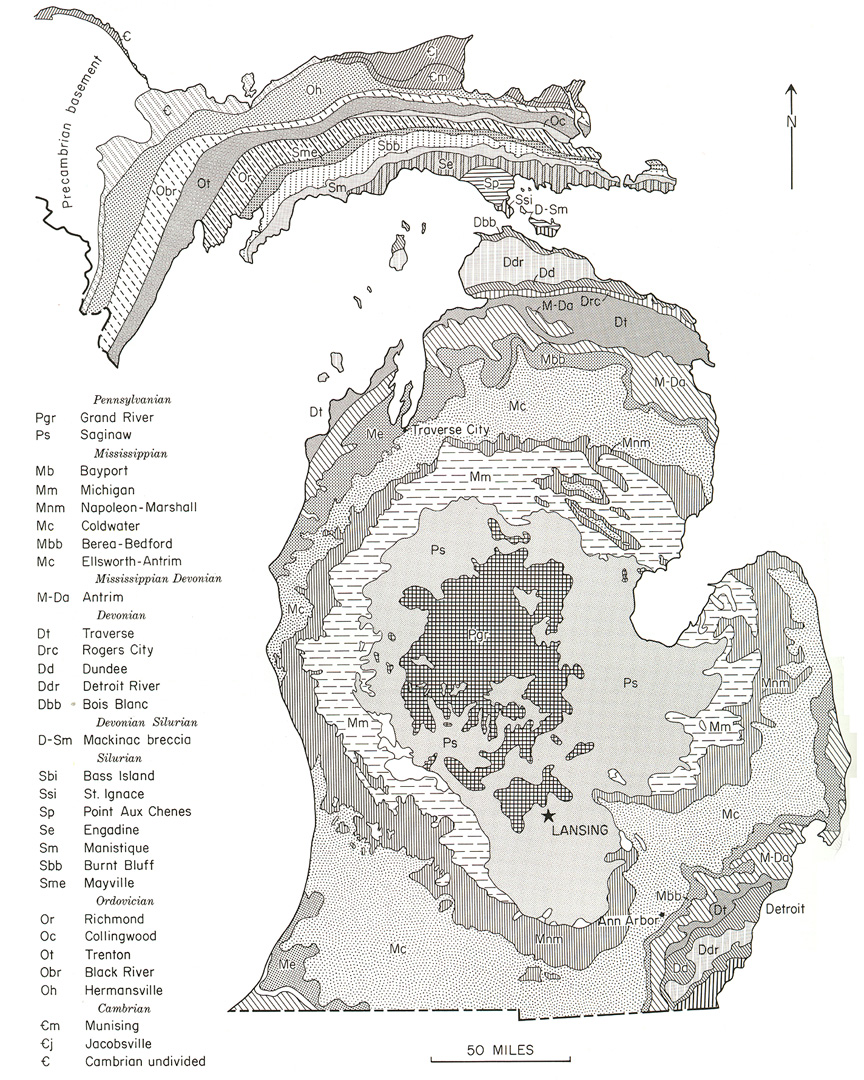

The major rock structures of the Great lakes region are shown in the map below. Notice the

Michigan Basin, the Keweenaw

Fault, the Superior Syncline, the Kankakee, Findlay and Cincinnati Arches, and the three

iron ranges of the UP. The Wisconsin

Dome is labelled the "Wisconsin Arch" on the map.

Source: Unknown

And finally, the map below is a detailed depiction of the Paleozoic rocks of Michigan.

Source: Unknown

As you now know, the geology of Michigan is dominated by two rock formations: the

sedimentary Michigan Basin, which covers the entire Lower Peninsula and the eastern half

of the Upper Peninsula, and the old crystalline, igneous shield found in the western Upper

Peninsula. These rocks are covered to various depths by material deposited during the Ice

Age. The preglacial topography was much disturbed by the power of these vast ice sheets as

they eroded and leveled certain areas and deposited materials in other sections of the

state. The present surface is characterized by ridges of sand, gravel, and clay known as

moraines, which were deposited as the ice advanced and retreated in the state.

Within the major landform regions, the great variety of glacial

features, each used somewhat differently by humans, results in a large number of smaller

regions, some even microscopic in size. In a small area, such as a county, three of four

or more local landform categories can be identified.

Parts of the text on this page have been modified from L.M. Sommers' book entitled, "Michigan: A Geography".

This material has been compiled for educational use only, and may not be reproduced without permission. One copy may be printed for personal use. Please contact Randall Schaetzl (soils@msu.edu) for more information or permissions.