ESKERS

In over a thousand places in the State we find long

narrow hills that look like abandoned railway embankments and locally are

called "hogsbacks" and "Indian trails." Geologically these hills are

eskers --- long narrow winding ridges of stratified gravel, sand and silt.

They formed under stagnant rather than moving ice. Often not recognized as

being glacial features, are the low, sinuous hills that can stretch for

miles and often resemble snakes when seen from the air. These are

eskers.

An

esker is an ancient river bed that has been formed inside or on top of a

glacier. As meltwater seeks to escape from the lower levels in the

glacier, it forms channels along zones of weakness and eventually emerges

from under the ice at the glacial margins. In its passage, the water

transports silt, sand and rocks and lays them down along its narrow

course. The water is unable to escape laterally because of the confining

walls of ice, and the stream bed is gradually built up above the level of

the ground on which the glacier rests.

Eskers were formed by deposition of

gravel and sand in subsurface river tunnels in or under the glacier. The

mouths of the tunnels became choked with debris, the melt water was ponded

back and dumped its load of sediments in the channel. The most famous and

longest esker in Michigan is the Mason Esker, which runs from Dewitt

through Holt and Lansing, and ends at Mason. Most of the Mason esker has

been removed, its sand and sorted gravel used to make concrete highway

construction.

Most eskers are on till plains

although some are known to cut through moraines and even cross drumlins.

They vary in length from a fraction of a mile to scores of miles, and in

height from a few feet up to several hundred and more feet. More than a

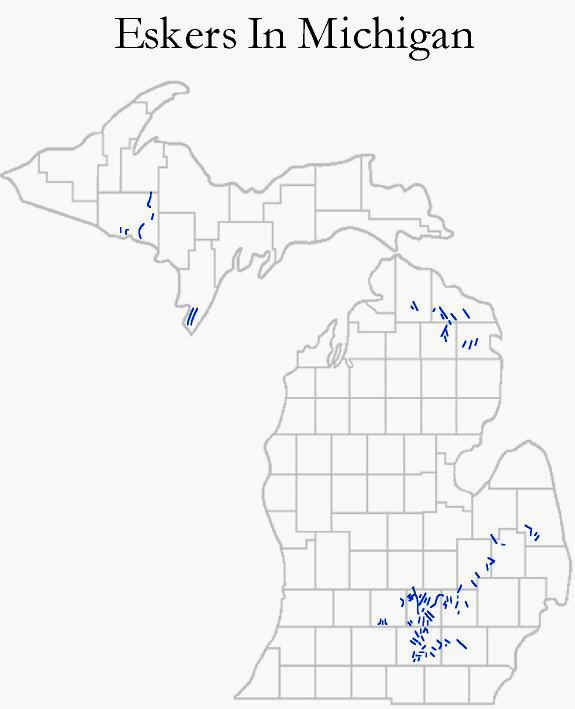

thousand eskers have been found in Michigan.

Just as rivers on land carry and deposit sediment, meltwater that flows

in the openings beneath, above and within a glacier also carries and

deposits sediment. Tunnels near the base of retreating glaciers fill with

transported sediments, which remain as

sandy or gravelly ridges that

look like upside-down stream beds after the glacier melts away. The ice

that formed the sides and roof of the tunnel subsequently disappears,

leaving behind sand and gravel deposits in ridges with long and sinuous

shapes.

The shape of an esker (in cross-section) is shown in the

cut below.

The image below shows

the stratified sand and gravel within the Osmun Lake esker, in Presque

Isle County, Michigan.

Eskers can be 500

to 600 kilometers long and, depending on the pattern of the glacier's

inner tunnels, can interconnect

in a pattern of central ridges and

tributaries, just like a branching river system. As you can see,

the esker is being mined as a source of aggregate.

Since eskers are made up of highly porous sand and gravel, they are

frequently excavated for construction. They are considered an endangered

geomorphological species since they have been used either to develop

roadways -- offering natural elevated, dry terrain -- or they have been

ripped up for the gravel to build nearby roads. For centuries in northern

Canada,

Inuit and wildlife have typically used eskers for high and dry

travel routes. More recently, eskers have been used in the hunt for

diamonds. Since they lie in the direction of glacial flow, prospectors

have used eskers to trace where minerals glacially eroded from

diamond-bearing formations have been transported. They trace these

"indicator" minerals "upstream" in an esker until they abruptly disappear:

this indicates the diamond source is

nearby.

This material has been compiled for educational use only, and may not be reproduced without permission. One copy may be printed for personal use. Please contact Randall Schaetzl (soils@msu.edu) for more information or permissions.