COASTAL DUNE SYSTEMS

Coastal dune systems form where sands on wide beaches are blown up into large dunes.

Coastal dunes are found predominantly along the eastern shoreline of Lake Michigan

from the Indiana state line to the Straits of Mackinac. Additional dunes are found along

the Great Lakes shoreline in eastern Saint Clair, Alger, Luce, and Houghton Counties.

Coastal dune sand is generally free of silt and clay, has a common range of grain sizes,

and is generally more rounded than other types of sand deposits. Coastal dunes usually

reach a height of over 100 feet above the surrounding terrain and form prominent knolls,

peaks, mounds, and ridges. When not stabilized by vegetation, they are extremely unstable

and migrate in the direction of the prevailing winds. Good examples of coastal dunes may

be found at Silver Lake State Park in Oceana County, Warren Dunes State Park in Berrien

County, and in the Sleeping Bear National Lakeshore in Benzie and Leelanau Counties.

The major sources of the beach sand, and hence the dune sand, is

twofold: rivers that enter the lake and bring sand to the beach, and erosion of

bluffs. High lake levels, as have occurred at many times in the geologic past on the

Great Lakes, encourage more sand to be eroded from the bluffs. This sand is then

delivered to the beach, where it is washed clean by waves and made ready for transport by

the wind, into the dune system. Thus, dune building episodes occur most commonly

when lake levels are high.

Dr. Alan Arbogast, a Geographer

at MSU, has spent much of his career studying sand dunes, and incorporates much of his

work into his classes. He spends a lot of time roaming around on dune landscapes,

like the one near the Lake Michigan coast (below).

Wave action sorts sediment well, with the fines being carried into the deep water where

they settle out and the pebbles and sand grains remain in the shore zone. As long as the

beach remains damp, the wind cannot pick up the sand grains. However, when the beaches

become dry the exposed sand can blow in the winds. Once a dune is formed, it continues to

grow in size.

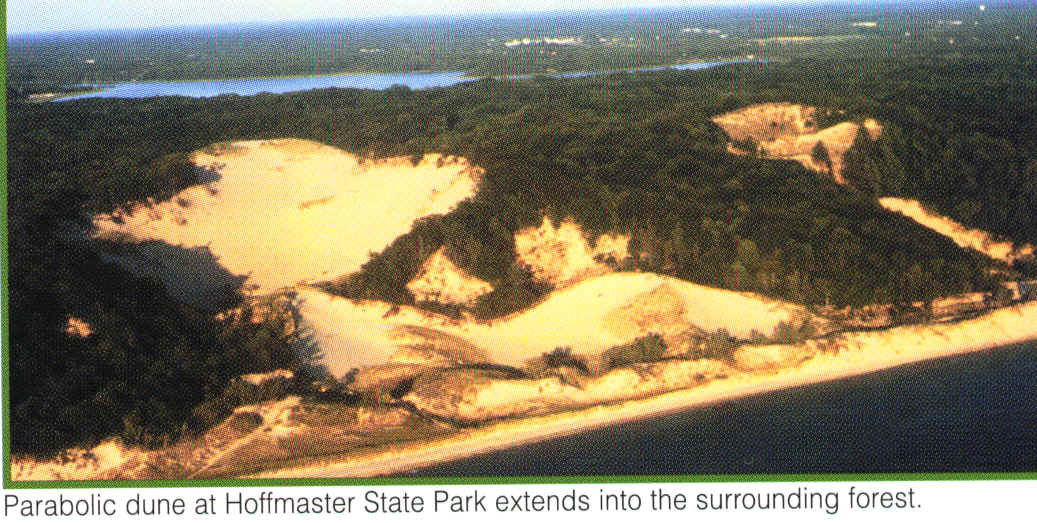

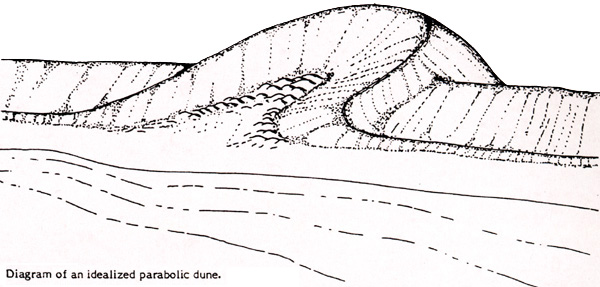

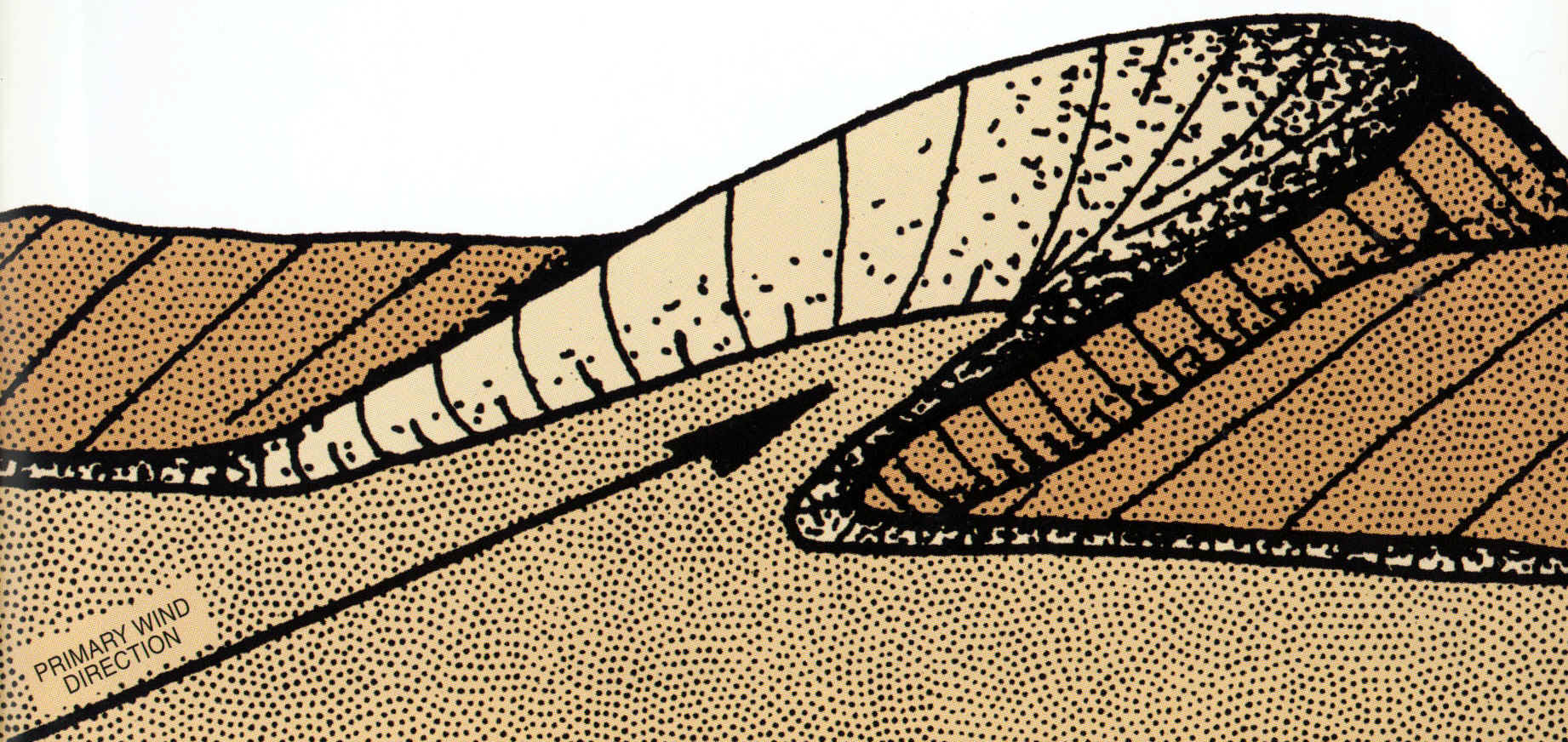

Thus, sand is blown up into large dunes, and the type of dune that

usually forms in this system is parabolic (see below). Sand is usually moved by the

process known as "saltation" in which individual grains move in a bouncing,

skipping course of violent collisions. The particles themselves, very seldom get more than

one foot off the ground. In this process, the sand can

exert considerable abrasive action on metal, wood, glass and boulder.

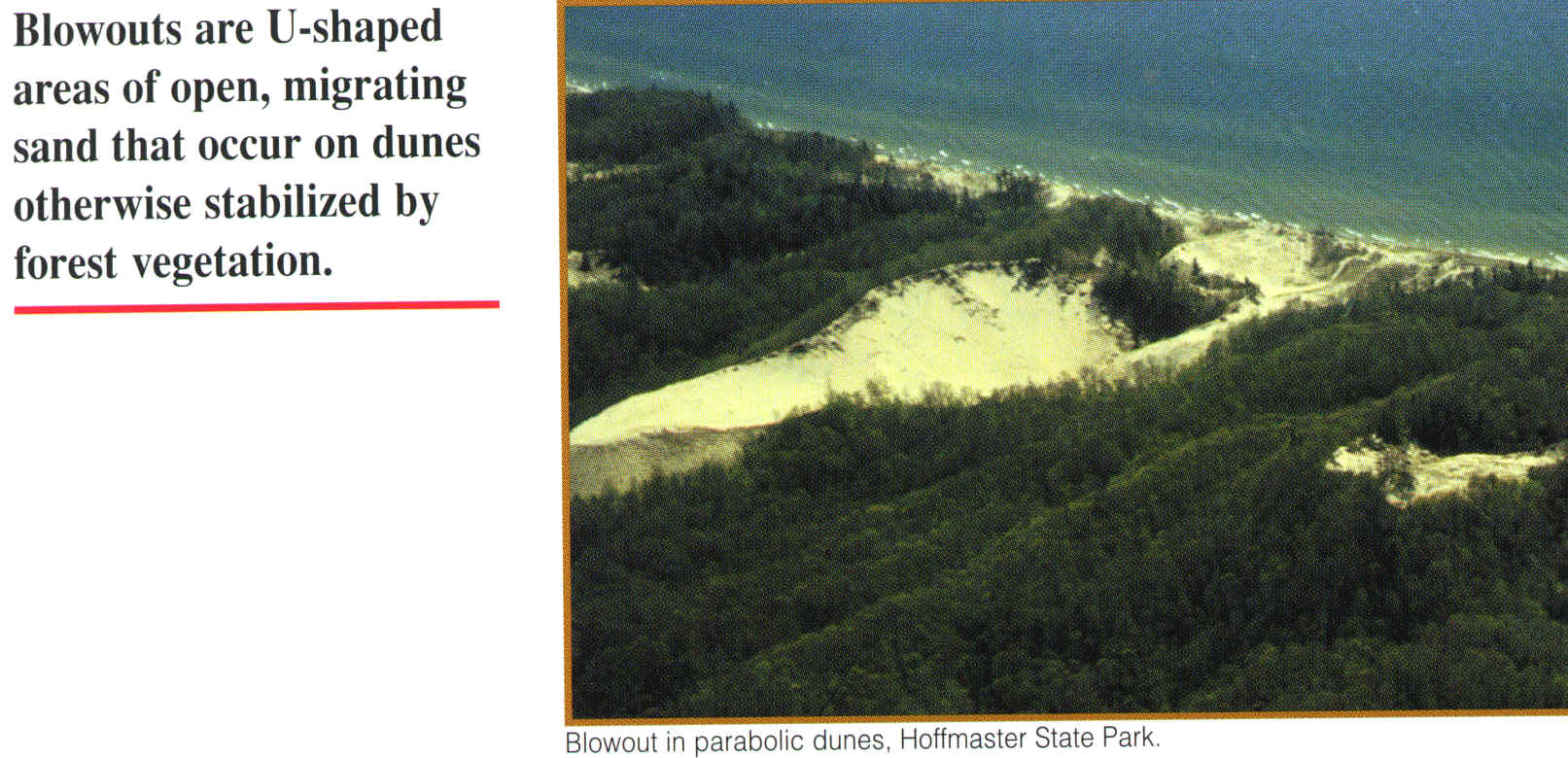

Parabolic dunes form on a surface that has sand but only a little vegetation. The

sand is allowed to blow, creating a blowout area where no vegetation is available to hold

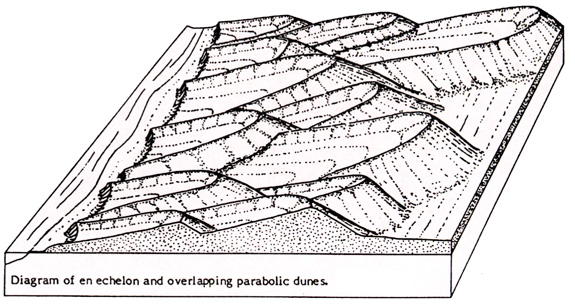

it down. Most of the dunes on the lakeshore areas are simply "seas" of

parabolic dunes, as shown below.

As can be seen below, the dunes front directly on the lake in places, while at others

there is a significant beach between the dunes and the water. Parts of the dunes are

stabilized, while other parts are actively eroding or being buried by additions of sand.

Clearly, this is a dynamic landscape.

Unusual plant habitats are to be found in the sand dunes along the eastern shoreline of

Lake Michigan, where a combination of coarse soils, diverse terrain, reduced summertime

evaporation and daytime temperature, an extended growing season, and a moderation of

severe winter cold because of the nearby water has permitted an extraordinarily rich

mixture of plants to coexist. Within Berrien County, particularly, small areas of dune

landscape contain a greater number of plants than is found in any other comparably sized

area of the state. Northward along the dunes, from about Muskegon, the vegetation becomes

more boreal but remains complex and locally varied.

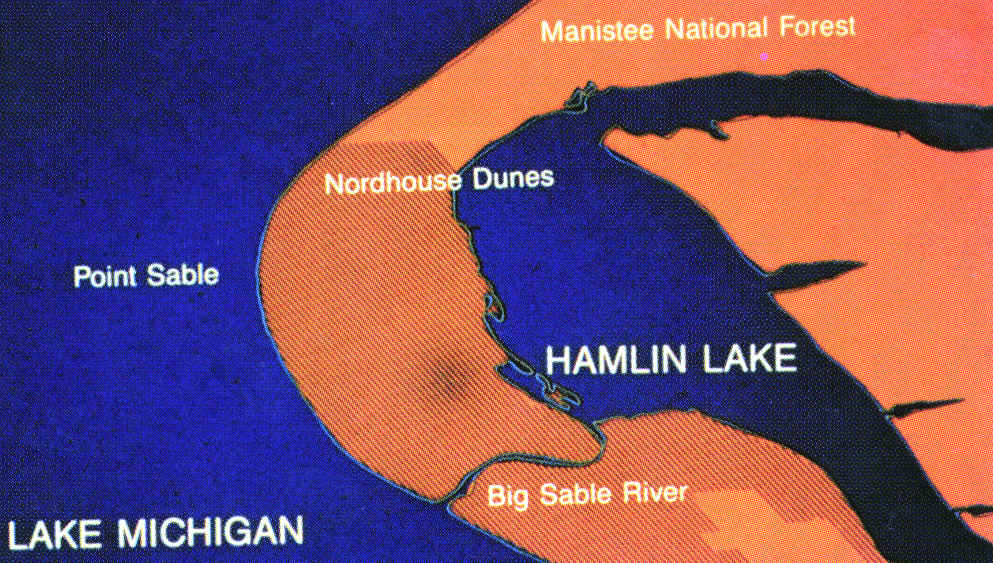

Some of the more famous and pristine coastal dunes in Michigan are the Nordhouse dunes,

north of Ludington.

Parts of the text on this page have been modified from L.M. Sommers' book entitled, "Michigan: A Geography".

This material has been compiled for educational use only, and may not be reproduced without permission. One copy may be printed for personal use. Please contact Randall Schaetzl (soils@msu.edu) for more information or permissions.