THE MICHIGAN BASIN

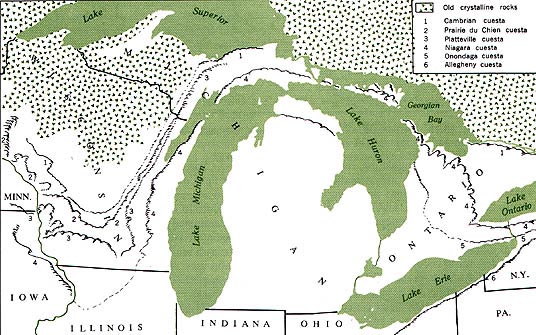

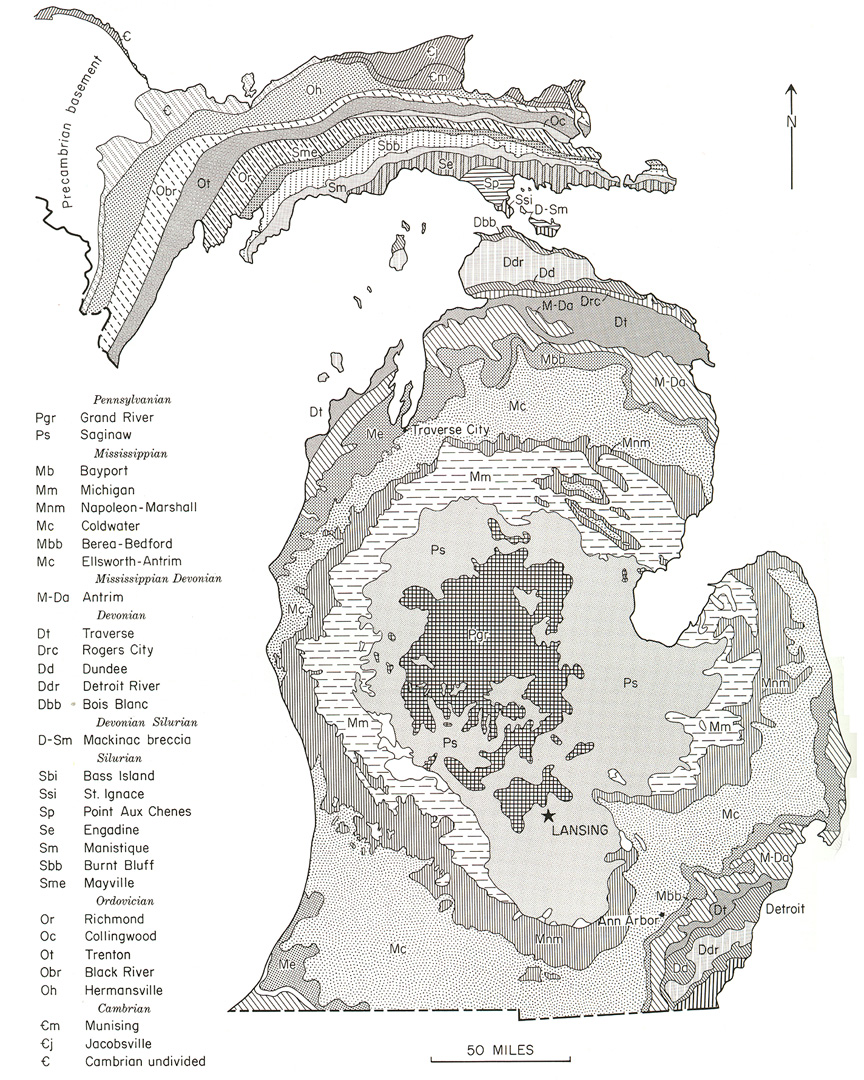

There is a marked contrast between the old, resistant Precambrian and

Cambrian rocks of the western half of the Upper Peninsula and the sedimentary rocks of the

rest of Michigan. The limestones, sandstones and shales, which dominate the Michigan Basin

of the lower peninsula, are approximately 500 million years old, some perhaps less. The

sediments that form these sedimentary rocks were deposited on the bottoms of ancient seas,

and the rock layers are piled on top of each other like saucers. The edges of the

sedimentary rocks appear at or near the surface in northern Michigan-for example, near the

Straits of Mackinac. In the center of the basin, they are about 14,000 ft (4,267 m) thick.

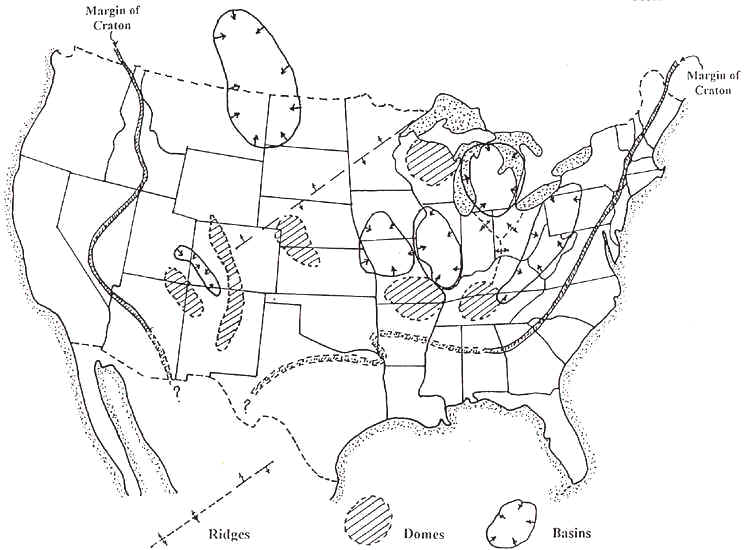

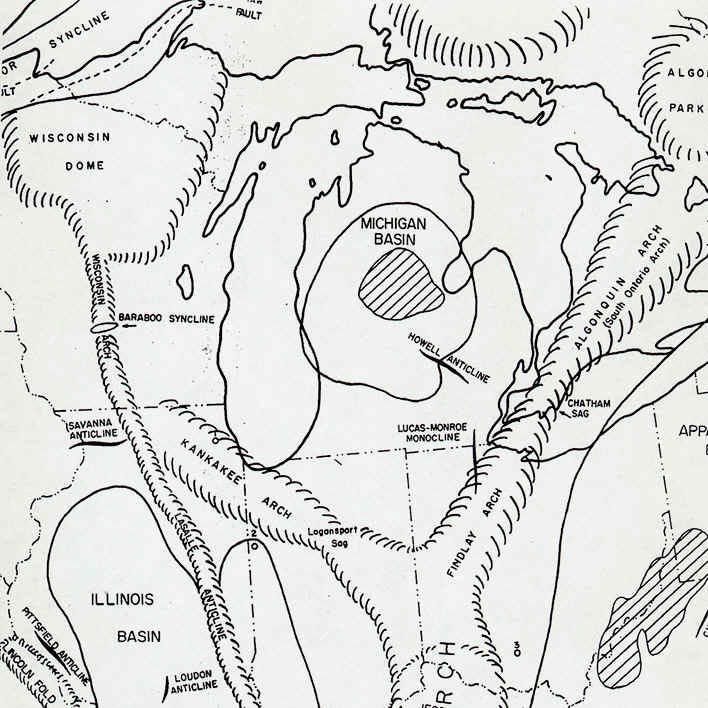

Many sedimentary rocks are laid down or deposited onto landscapes that have

been either upwarped into domes, or downwarped into basins. Rarely or never is the

"basement" flat-lying; the map below shows the many domes and basins in the

continental USA.

Source: Unknown

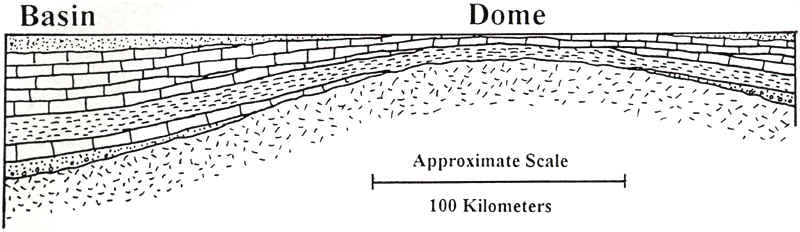

Michigan is no exception. The diagram below shows that, if a dome is preexisting, as the basement, the sedimentary rock layers will thin on the top of the dome. Likewise, such rock layers will be thicker in the basin center.

Source: Unknown

Source: Unknown

Source: Unknown

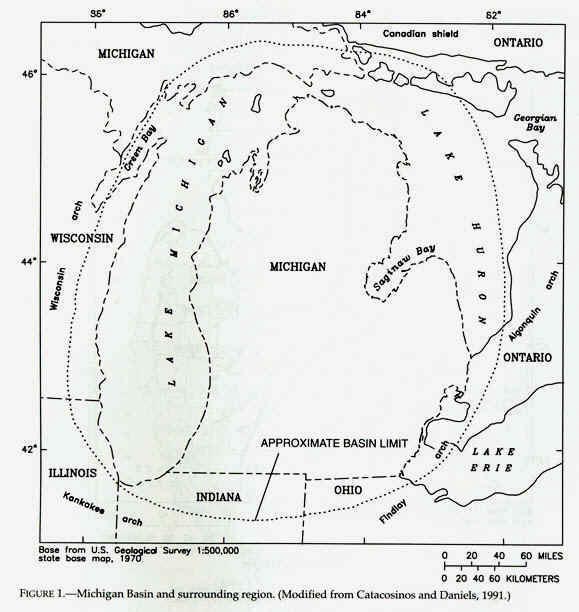

Just how aerially extensive is the Michigan basin? The map below provides a good

indication.

Source: Unknown

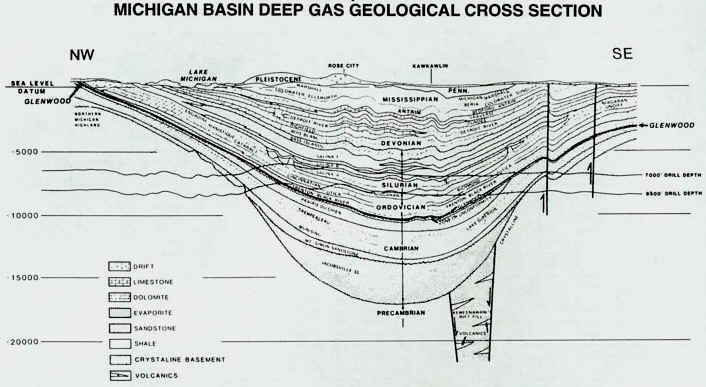

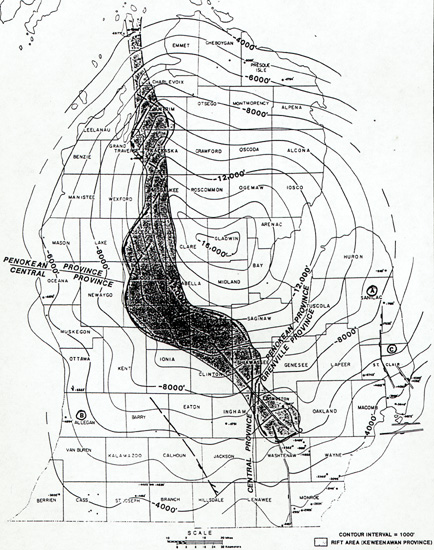

Just how deep and how much depression exists within the basin? Examine the map

below, which shows isolines that ring the basin. Each line illustrates the depth to

the Precambrian basement rocks, which comprise the floor of the Michigan basin. Note

that the center of the basin, in Gladwin County, is 16,000 feet below the surface!

Likewise, the edges of the basin, such as at Mackinac City, are only 4000 feet down.

Source: Unknown

The basin, in cross section, looks about like this:

Source: Unknown

Source: Physical Geography of Wisconsin, Martin.

In summary, a shallow sea spread over the continent as the Paleozoic era began. The

Paleozoic era was a long, quiet period of slow earth movement and oscillations of sea

level which caused twenty-four to thirty minor retreats and transgressions of the sea

across the Great Lakes region. At times the seas were warm and clear, supporting a myriad

of shelled creatures, at other times the seas were muddy, receiving great volumes of fine

silts and decayed vegetation from low lying land. At times desert conditions prevailed,

and the seas became excessively salty supporting little life, or were brackish with gypsum

and sulfide and chloride minerals. At other times the sea became a shallow, huge swamp

that supported vegetation. Each sea left its records in the sediments piled and spread on

its floor. The sediments compacted to rock. The floor of each sea became the basin of its

successor; thus each sea was smaller and within the boundaries of its predecessor.

Eventually the Michigan basin was filled with a succession of shallow bowl-shaped rock

formations, one within the other. Bowls made of sandstone, limestone, shale, rock salt,

gypsum in all degrees of purity ---- shaley-limey sandstones, sandy-shaley limestones,

shaley limestones, sand shales, and all other combinations of sediments one can describe.

The formations differ in thickness, some are wedge and not bowl shaped, and do not extend

across the entire basin --- we have records which show that barriers prevented the seas

making a complete submergence. But the Paleozoic formations of Michigan have a common

characteristic, they all slope or dip from their rim edges to the center of the basin.

The Michigan Basin is one of the greatest areas of rock salt

accumulation in the world, and these sediments have been the basis of major chemical and

plasterboard industries in Michigan. How did these sediments come to accumulate in such

great thicknesses in southern Michigan?

During the early and middle Silurian, an extensive blanket of limestone

was deposited from New York State west at least as far as Wisconsin. Within this area of

carbonate deposition, however, some localities subsided much more rapidly than others. One

of the areas of subsidence was located under what is now lower Michigan. Indeed, the

development of the Michigan Basin is the dominant feature developed in the Great Lakes

region during the Silurian.

Earlier, during the Cambrian and Ordovician periods, one rather

elongated basin extended from Missouri northeastward through Illinois and lower Michigan.

This basin was bounded on the northwest by the Wisconsin Arch and on the southeast by the

Cincinnati Arch. During the middle Silurian the Kankakee Arch developed across

northeastern Illinois, forming two separate basins. Although it did not form a land

barrier, it greatly restricted circulation of sea waters within the Michigan Basin.

Source: Unknown

Source: Physical Geography of Wisconsin, Martin.

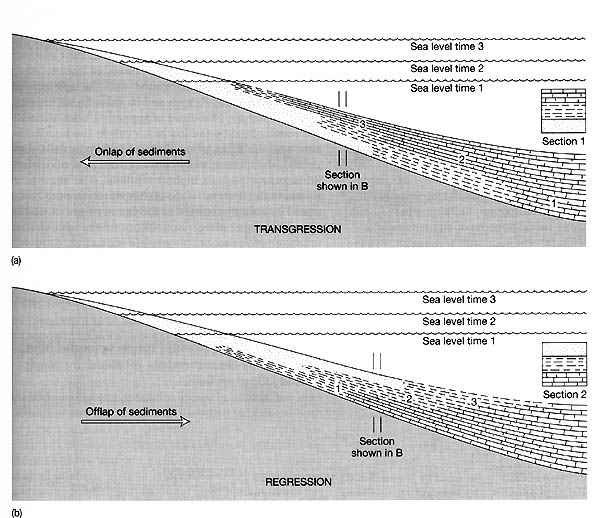

Transgression (the sea moving onto the land) and regression (the opposite) are important concepts to know when discussing sedimentary rocks. Transgression and regression were very important parts of the depositional environments of the Michigan basin during the Paleozoic. During transgression, the rate of sea level rise is greater than the rate of sediment supply, resulting in onlap of sediments ("a" below). Typically, we then see rocks that change, generally, from sandstones to shales to limestones, as we move upward in the rock column.

During regression, the rate of sediment supply exceeds the rate of sea level rise, or the sea level falls, causing offlap of sediments ("b" below). In this case, the rock column is (from bottom to top) limestone, shale, sandstone.

Source: Unknown

This material has been compiled for educational use only, and may not be reproduced without permission. One copy may be printed for personal use. Please contact Randall Schaetzl (soils@msu.edu) for more information or permissions.